Five tendencies that could impact the future development of Afghanistan

- The internal cohesion of the Taliban is challenged, but keeping the movement united is a priority

Internal legitimacy was an important factor when the Taliban formed an interim government. The movement is sociologically less homogeneous than before, and the greatest lines of divisions are between the Kandahari Taliban (the original group) and the “Haqqani Taliban” (an independent movement since the Cold War).

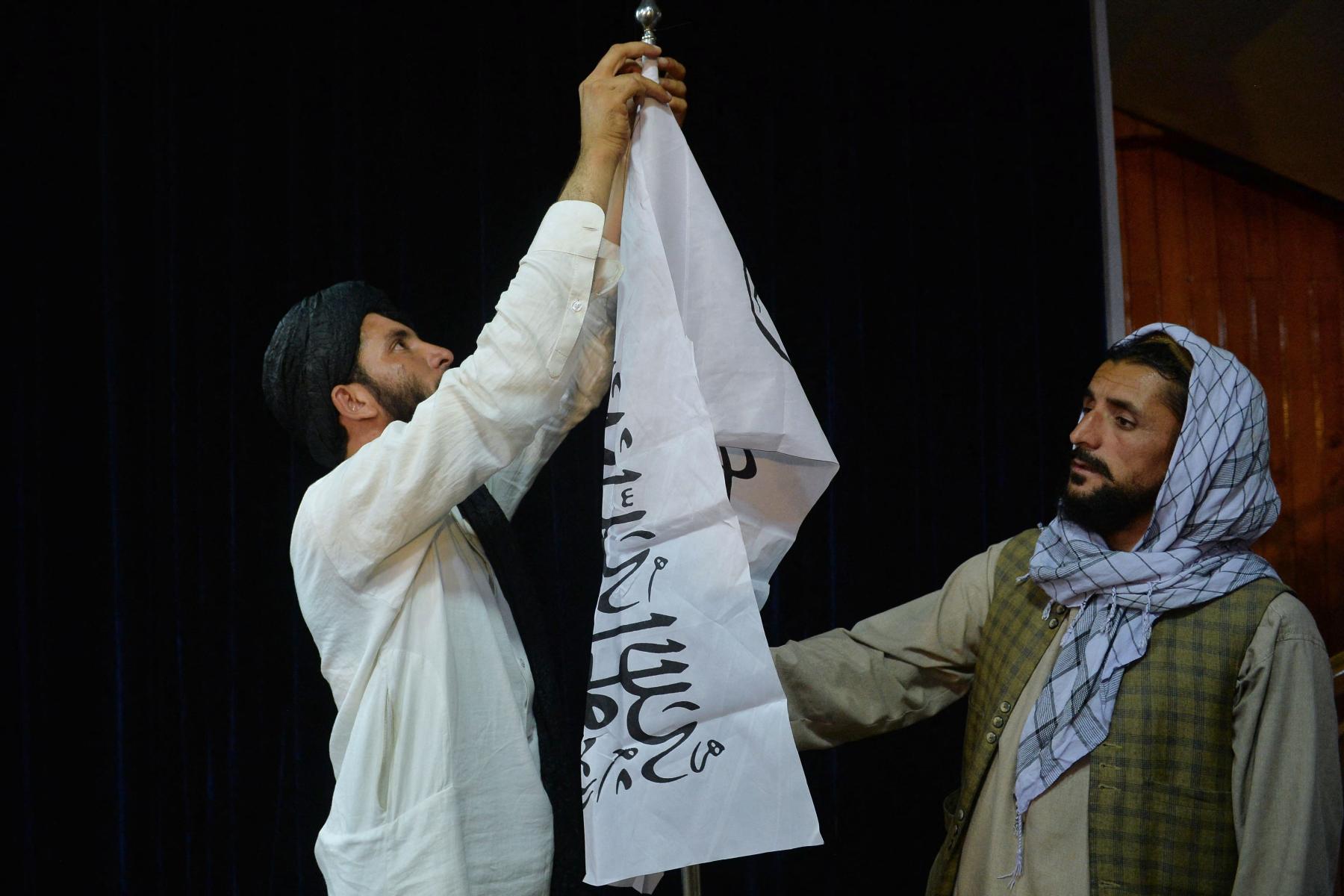

The Taliban announced its ambition to be pan-Afghan (embracing all ethnicities) after ascending to power in august 2021, and some provinces and districts have non-Pashtun governors. From the Taliban's point of view, the criteria for an "inclusive government" proved to revolve around rewarding adherents who have fought for nearly 20 years, rather than including ethno-religious minorities and women.

Internal tensions are not just ideological, e..g. how far one can go when it comes to freedom rights or regarding the bonds to Al-Qaeda, but also pertain to material interests and power. For example, a local commander revolted against the centralised leadership’s desire to take control of mining operations. The conflict started when he refused to surrender his tariffs for the mines.

Ideological differences are also tied to material ones. The Haqqanis could potentially become more influential in the movement if they acquire greater control of the mining sector.

Generally, there is variations in the way the Taliban implement their power and policies (e.g. differences in attitudes regarding school attendance of young girls), and in practice it is a minority of the Taliban that define key policies.

- External resistance is not united, but comes from different fronts

There has been an increase in anti-Taliban attacks in the northern provinces in particular (Samangan, Balkh, Baghlan and Takhara), and the National Resistance Front and other anti-Taliban groups are trying to mobilise support. In Herat, several attacks were conducted on Taliban forces. In Panjshir, there has been low intensity fighting and the Taliban have increased checkpoint numbers.

According to the UN, the Islamic State (ISKP) has also increased its presence in northern and eastern Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover, but its overall size is unknown. The ISKP has occasionally collaborated with the Pakistani Taliban (TTP), but has increased attacks on the Afghan Taleban, on Shia Muslims/the Hazaras, and on Hanafi clerics (the Taliban adheres to the Hanafi school of law).

The Taliban has shut down salafi mosques (AQ and IS are both Salafi jihadi movements), and there have been reports of forced conversions. And since the death of Al-Qaeda leader, al-Zawahiri, in Kabul recently, tensions have also heightened between the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

There is no united front against the Taliban but a handful of militias have been active against the Taliban, some of which are led by former members of Afghan army special forces.

Relative peace has prevailed in the country since the Taliban’s seizure of power, and armed resistance is less of a challenge to the regime today than during the first Emirate in the 1990s. At that time, the Northern Alliance was internationally recognised, represented in the UN and received weapons support. There is no rival government or democratic opposition to the Taliban, but there are active and critical civil society initiatives that advocate for women’s rights, and freedom rights.

- The Taliban is developing a neighbourhood policy which is about non-interference and trade, but there are current tensions with Pakistan and Iran

The central government has a policy of becoming financially independent from the west (a narrative that has resonance due to decades of foreign aid dependency), and their diplomatic and trade orientation is towards China, Russia, Iran, Pakistan, and the central Asian countries.

They have had conversations with Qatar regarding weapons trading, and received technical and diplomatic support from Qatar, where they still have a “diaspora” (In Doha the Taliban had their representation office for years during the foreign involvement in the country). China has opened a mining office in Kabul and talks between the two countries have centered on supporting Afghan traders and the removal of tariffs on Afghan goods.

There are tensions with Iran over water (control of the Helmand River), which is both an historic tension but also one that has escalated due to climate change issues and devastating droughts in both countries. Other issues raised by Iran concern anti-Shia campaigns in Afghanistan (Iran fears a spill-over), although thus far the ISKP have taken responsibility for all attacks.

There have been tensions between the Taliban and Pakistan after the former doubled its low coal prices to its export partner Pakistan. Further tensions arose when the Taliban announced their interim government last year, which did not include representatives from other Afghan factions, as they had assured Pakistan it would. Pakistan has also seen a rise in TTP and ISKP activities, and like Iran, has been concerned about escalation mechanisms that could further affect the situation in Pakistan.

- There is an economic and humanitarian crisis, but the Taliban strategy is regional trade.

In 2019 – prior to the Taliban takeover – around half of the country's population lived below the official poverty line. In early 2022, the UNDP estimated that 97% of Afghans are at risk of falling below that limit. The Taliban want the west to unfreeze Afghan assets (the country's reserves of more than $9 billion abroad), and has successfully blamed the west for the humanitarian crisis that Afghans are facing. Even technocrats from the former government have been vocal on this, including the former president Hamid Karzai. To overcome the scale of the humanitarian crisis requires a functioning state and a steady flow of funds. However, a principled approach regarding the Taliban stands in the way, and there seems to be an unresolved tension between the human rights agenda on one side and the humanitarian agenda of the west on the other.

Afghanistan has huge deposits of copper, iron, marble, talc, coal, lithium, gold, gemstones (and oil and gas), making Afghanistan one of the world’s most resource-rich countries, and the Taliban has announced they want to exploit this potential. Though the regime is vulnerable, it hence also has some options connected to this.

Before the Taliban took power, the annual OECD aid was around $4 billion, and according to the World Bank, international aid covered about 75% of government expenditure. The current humanitarian needs are partially being addressed by international aid organisations who have been able to continue working in Afghanistan.

Customs on trade is traditionally the state's main tax source and it will rise if border traffic resumes. The tax value of trade with Iran alone is estimated at $235 million annually under ordinary conditions. Taxes on smuggling and opium cultivation also generate income.

Isolation and sanctions by the west might either strengthen the Taliban's opponents (since they make it hard for the Taliban to deliver any services to the Afghan people) but it might also provide them with legitimacy, since western sanctions can be blamed. The sanctions have not prompted the Taliban to make major concessions when it comes to their “rights agenda” but it is de facto strengthening the regime's cooperation with states that are not bound by principles of democracy and human rights.

The Taliban is further focused on creating an interest-free economy in line with their interpretation of sharia, and they have shown little interest in western funding. However, whether this sort of idealism will prove helpful in a situation where there are also many internally displaced people, not least due to water shortages, is doubtful.

- Policy on human rights will remain ultra-conservative, but there will be variations in implementation.

The Taliban has implemented widely varying educational policies in different provinces, though there is still a national ban on schooling for girls from the 7th grade upwards. Lack of salaries and ensuring segregation has thus far been the Taliban’s explanation for the “delay” in reopening schools.

As described in historical accounts of Afghanistan’s political setup, the identification of Afghanistan as a centralised state has always been weak, and restrictive policies will not necessarily be implemented equally. The same challenges of a weak centralised state will doubtless also apply to the Taliban.

There are few indications that the Taliban will succumb to sanctions and isolation. International promises of recognition and broader economic cooperation are currently not altering Taliban political attitudes. On a local level there is variation in the way policies are implemented, though the central leadership in Kandahar is trying to consolidate control over local governors and commanders. The Taliban are consulting religious clerics from other countries to discuss the limitations of sharia, so any change will most likely come through such consultations.

A significant number of the old state administration stayed on after the collapse of the Afghan government, and the Taliban has retained the existing organisational structure (an addition being the revival of the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice).

The political leadership of the ministries was replaced, while retaining lower-level government employees. However, the latter do not receive salaries on a regular basis, so the state apparatus is certainly not functioning in a business as usual mode. In the future variations in the implementation of decrees from Kandahar should be expected, and will most notably be seen as a difference between urban and rural areas.

DIIS Eksperter