Transnational threat or PR stunt? When jihadist groups declare allegiance

Both al-Qaeda and Islamic State have suffered major blows in recent years. High-ranking al-Qaeda leaders have been killed in Afghanistan, Algeria, Pakistan, Syria and Yemen. By March 2019 IS had lost the last pockets of the territory it controlled in Syria and Iraq, and later that year Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, IS’s self-declared “caliph”, was killed in northwestern Syria. However, at the same time, the number of countries in which al-Qaeda and IS-affiliated groups operate has hardly changed at all. As local authorities and the international community attempt to deal with these groups, the question of what it actually means when insurgent groups claim allegiance to a transnational organisation has become important. In this interview, PhD fellow Dino Krause addresses one of the currently most discussed questions among academics in the field of jihadism…

What does it mean for a jihadist group to pledge allegiance?

This is currently being debated among scholars, and there is no simple answer. When trying to determine what these pledges of allegiance mean, scholars have been looking at changes across different dimensions. First, framing: who do they threaten in their statements? What types of religiously-founded arguments do they invoke to justify their violence, and to which external actors are they signalling support? Second, propaganda: affiliation may influence both style and quality of the group’s propaganda material, as they get access to new al-Qaeda or IS-affiliated media channels.

Overall, we can say that armed groups do not immediately transform into a transnational terrorist threat as soon as they declare their allegiance to al-Qaeda or IS, but that this is not to say that such a move is insignificant.

Third, targets: do they attack military or civilian targets? Domestic or foreign military targets? And what groups of civilians do they target? Fourth, tactics: in some instances battlefield tactics change because groups get access to military training, bomb-making expertise etc., through the connection to a transnational organisation. And finally, we have to look at the influx of foreign fighters to these groups that may result from the groups’ increased transnational framing of their insurgency.

Some researchers highlight the fact that these groups primarily recruit locals, that their conflicts are driven by local grievances, and that their allegiance to a transnational organisation primarily serves signalling purposes, in order to build up an image of strength.

However, other scholars, while rarely disputing these arguments, add that the formal integration into al-Qaeda’s or Islamic State’s organisational structure has important consequences: they point towards the inflow of foreign fighters, weapons and funds, or to the changes in the framing of local insurgencies after groups pledge allegiance to al-Qaeda or Islamic State.

Overall, we can say that armed groups do not immediately transform into a transnational terrorist threat as soon as they declare their allegiance to al-Qaeda or IS, but that this is not to say that such a move is insignificant. Rather, there is an interaction between local factors and transnational influences, which shapes the course of these insurgencies.

Do Islamic State and al-Qaeda differ in terms of how their affiliated groups act?

Yes, they differ to a substantial extent. When Islamic State was led by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and split from al-Qaeda in 2014, the group took its particularly repressive strand of jihadism, known as "takfirism" (which implies the excommunication of fellow Muslims due to allegedly “apostate” behaviour) to hitherto unseen levels of brutality. Ever since, a hallmark of IS-affiliated groups around the world has been their brutal and self-publicised violence against, often Muslim, civilians.

In this regard we see that, after declaring allegiance to Islamic State, militant groups take increasingly sectarian and anti-civilian action, attacking Christian civilians in places such as Nigeria, DR Congo, or Mozambique; or Shia Muslims in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Moreover, Islamic State became known for its drastically repressive governance once in control of territory, such as in Iraq and Syria between 2014 and 2019, whereupon the group also expanded its rigid governance guidelines to its affiliate groups in other places, such as Sirte in Libya, characterised by the destruction of public sites it deemed “apostate”, and public floggings, amputations, or executions for allegedly transgressive behaviour.

In contrast to many IS-affiliates, al-Qaeda’s branches tend to be more hesitant when it comes to carrying out mass-casualty attacks against Muslim civilians, or to publicly executing civilian prisoners.

In contrast to many IS-affiliates, al-Qaeda’s branches tend to be more hesitant when it comes to carrying out mass-casualty attacks against Muslim civilians, or to publicly executing civilian prisoners. Of course, the brutality of groups such as Jama'at Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin in Mali and Burkina Faso, or al-Shabaab in Somalia, should not be downplayed. Nevertheless, these groups direct the bulk of their efforts at fighting their military opponents.

Initially, when in control of territory al-Qaeda followed a highly repressive approach as well – for instance during the so-called Islamic Emirate of Azawad in northern Mali during 2012. However, the public resistance it faced from civilians sparked internal critique from within al-Qaeda’s own leadership, leading to a more strategic and careful approach to implementing Sharia-based legislation; for instance in Yemen, with al-Qaeda instructing its regional leaders to not antagonise local populations by imposing overly drastic regulations.

Another indication that al-Qaeda and IS-affiliation are more than just rhetoric is that these groups have clashed with each other on several, widespread, battlefields ranging from Mali and Burkina Faso to Syria, Somalia and Yemen. Many scholars once speculated that al-Qaeda and IS-affiliated groups might well join forces to fight against governments, yet this has not occurred in any of these countries. Rather, the result has often been bloody infighting between the different jihadist factions.

How is the relationship to the so-called “mother” organisation?

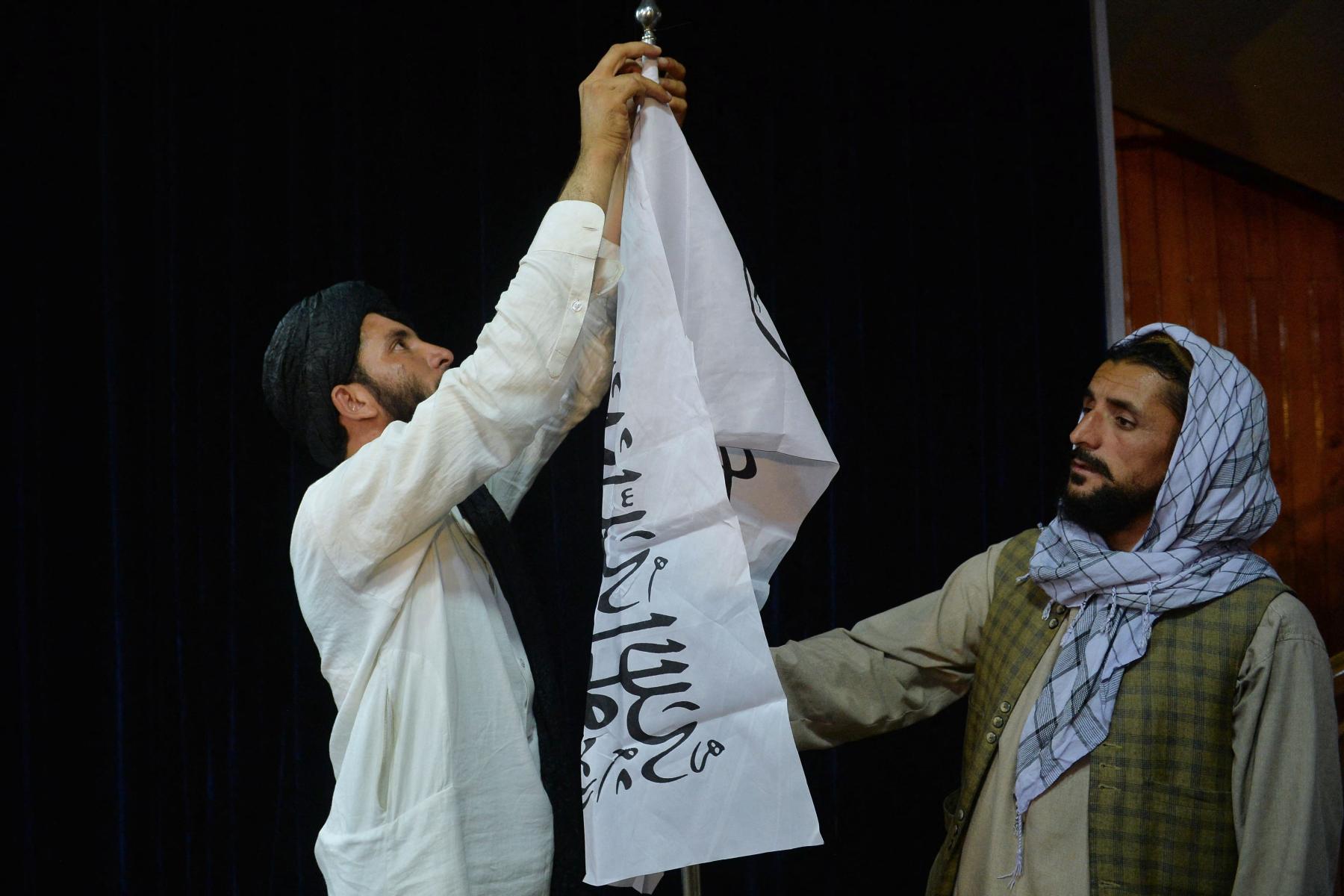

The particular forms of support provided by al-Qaeda and Islamic State to their regional affiliate groups have always depended on the core organisation’s own strength. This point is particularly relevant given the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan and the possibility that Afghanistan could – once more – become a safe haven for al-Qaeda. Should such a scenario materialise it would offer the organisation a chance to grow in its core territory, and to return to a level of organisational capability that would allow for a different form of support towards its regional branches around the world.

For instance, al-Qaeda once used to dispose of a considerable financial budget, which it channelled towards the Taliban in Afghanistan, but also to its affiliate organisations around the world. Recent prison raids conducted by the Taliban have released scores of al-Qaeda fighters, which will help the decimated core group to grow in size.

Furthermore, one major challenge for the group over the past years has been its inability to react quickly to political developments as its leadership was constantly on the run. Should al-Qaeda manage to regroup in Afghanistan, this would allow its leadership to be more present, and to reassert its relevance vis-à-vis other actors in the global jihadist movement.

Since the military decline of Islamic State began in Iraq and Syria, from 2016 onwards, its capacity to send weapons, money and foreign fighters to distant battlefields has decreased significantly as well. However, similar to al-Qaeda, given the already high level of autonomy of its local “provinces”, many of these have been hardly affected by events in Iraq and Syria.

Rather, they have continued their own insurgency campaigns, with most of them relying largely on local recruits and, in many cases, fighters from neighbouring countries. In turn, some IS provinces have basically ceased to operate, such as in Algeria or Bangladesh. However, in these cases it is primarily due to government crackdowns, rather than caused by the events in Iraq and Syria.

What does this mean for how these factions should dealt with by the international community?

...a group that proclaims itself as an al-Qaeda or IS-affiliate but employs few-to-no foreign fighters, and operates in a territorially very limited area, might be driven to a larger extent by local, rather than transnational concerns.

One important challenge to address when dealing with these insurgent groups is to understand their transnational and local linkages to a better extent. For instance, a group that proclaims itself as an al-Qaeda or IS-affiliate but employs few-to-no foreign fighters, and operates in a territorially very limited area, might be driven to a larger extent by local, rather than transnational concerns.

It is also important to understand, why people decide to join these movements: for instance, are the new recruits well-educated university graduates who join due to religious reasons, as was the case in Sri Lanka or Bangladesh? Or do they join because of non-religious factors, and only get religiously indoctrinated once they have joined the group, as analysts have noted with regard to how jihadists mobilise support in Burkina Faso and Mali?

Such considerations should be factored into decisions about how to tackle jihadist movements in different places. Lastly, military campaigns alone often not only have limited long-term success, but may in fact aggravate the situation, as they feed into the jihadist narrative of positioning themselves as fighting against a foreign oppressor. In any event, military successes will only lead to consolidated progress in the long run if they are complemented by an effective approach to address the root causes of the particular conflict.

Dino Krause is part of the DIIS project Transnational Jihad that explores transnational jihadist movements and the ability of transnational jihadist movements to tap into local conflicts, hence escalating violence.