Women, peace and security beyond resolutions

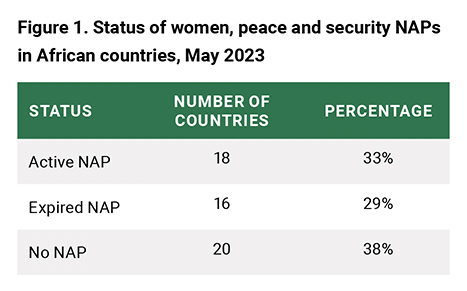

In 2000, the UNSC adopted Resolution 1325 on including women in peacebuilding and peacekeeping. Since then, countries across the world have adopted National Action Plans (NAPs) to adapt this resolution to national contexts. More than half of African Union member states have women, peace and security NAPs (see Figure 1), sometimes amidst situations of post-conflict recovery or ongoing escalations of violence.

- National implementation of the women, peace and security agenda should go beyond top-down approaches and include civil society throughout the policy process.

- Grassroots actors’ experiences of conflict resolution and local traditions of peacebuilding should be harnessed and integrated into policy making and implementation efforts.

- Many low-income countries commit to women, peace and security through national action plans (NAPs) but need technical support for improving NAP progress reporting.

Building on the research on women, peace and security agendas in Ethiopia, Kenya and Mali, and Africa more broadly, this policy brief identifies ways to enhance the practicality and benefit of NAPs for recipients. Research shows that while national stakeholders believe that NAPs are important instruments for interrogating women, peace and security implementation, NAPs are hindered by weak political will for implementation, lack of local ownership and irregular impact reporting. Due to their international mandate, the UNSC members can play an important role in promoting the national implementation of the women, peace and security agenda.

First, the knowledge and experience of civil society actors should be engaged strategically. Women’s informal mediation, notifying elders or authorities of pending conflict, returning stolen cattle, or forming peer groups are some examples of such practices. Secondly, country-level reporting on women, peace and security needs to be enhanced and reporting should aggregate between the state and non-state actors’ implementation efforts. Overly broad reporting frameworks fail to foster accountability regarding policy implementation.

- Evolves from UNSC Resolution 1325.

- Extended by 10 subsequent resolutions.

- Targets gender-inclusive peace activities.

- Addresses conflict prevention, resolution, negotiations, peacekeeping and reconstruction.

- Incorporates four policy pillars: participation, protection, prevention; and relief and recovery.

Global agenda in diverse African contexts

The NAP development and operationalization depend on the country’s political and security circumstances. Ethiopia, Kenya and Mali offer examples of women, peace and security NAP processes with varying opportunities for civil society engagement, local conflict resolution mechanisms and different monitoring capacities. While Ethiopia is recovering from conflict and is currently drafting its first NAP, Kenya has adopted a 2nd NAP amidst bouts of political violence, sporadic conflicts and counter-terrorism efforts. As a result of the NAP implementation reports, the second NAP in Kenya prioritizes localization efforts. Mali, while implementing its 3rd NAP, faces a deteriorating security situation, including attacks on civilians and a stalled peace process. The security context creates barriers for meaningful policy implementation across the country, particularly in terms of food, health and social insecurity. Consequently, NAPs are destined to look different and address the particularities of a specific country. However, similarities can be observed between NAPs in African countries.

Beyond the NAP: Engaging civil society

Much of the women, peace and security work takes place outside and beyond government-led NAPs. In Ethiopia, Kenya and Mali, the practitioners irregularly use NAPs to guide their activities on women, peace and security. Grassroots initiatives can involve looking after families of those lost to conflict, or donors may support organizations in eliminating sexual and gender-based violence– such initiatives can overlap with NAP objectives without referring to the document.

NAPs largely remain at a policy level and are perceived to be a top-down approach. These tendencies have led to a global push towards localization of the women, peace and security agenda through local action plans. For instance, Kenya’s second NAP focuses on the participation gap at county and community levels, and it takes into account that different localities may resonate with the women, peace and security agenda in different ways.

Women across Africa have a history of mobilizing for peace. Some famous examples include Women of Liberia’s Mass Action for Peace and the role of women in Rwanda in rebuilding the country after the genocide. Since this work takes place at different layers of society, civil society organizations (CSOs) are well-placed intermediaries between local, national and international stakeholders. They have broad networks, can switch between the official and vernacular language, they have resources to influence policy and hold government bodies accountable for implementation. However, civil society actors need a safe space to operate. For example, Ethiopia has seen waves of the opening and tightening of civic space in the past 20 years, which has hindered organizations’ capacity to advocate for policy change. Mali is witnessing increasingly strained relationships

between the state and civil society groups. Such tensions can impact women, peace and security NAPs, turning them into government artefacts rather than instruments for transformation.

- Embrace the four pillars of UNSCR 1325.

- Led by Ministries of Gender and Social Affairs (or equivalent) · In contrast, Western and Northern countries tend to place NAPs under Ministries of Foreign Affairs.

- Supported by UN Women technical and financial assistance.

- Policy development and implementation is often donor funded.

- Irregular reporting and monitoring practices

There is also a difference between self-organized local women and professional organizations. Historically, professional CSOs and NGOs tend to focus on ‘training’ and ‘capacity building’ rather than local practices of ‘everyday peacebuilding’. Engaging with local traditions of contestation and peacemaking can foster dialogue between locally and internationally proven strategies. For example, the Network of Ethiopian Women’s Associations’ report discusses diverse conceptualizations of peace in different parts of Ethiopia and acknowledges that the translation of women, peace and security is not a straightforward one. Their report takes local expressions of women’s participation in the maintenance of peace as a starting point for considering the application of a global agenda in Ethiopia.

Including the local actors in the national women, peace and security policy agenda should also consider the power dynamics between local elites, brokers and gatekeepers. One must be careful about romanticizing the notions of ‘community’ and ‘grassroots’ as a stable and homogenous whole. Local communities embody frictions, tensions and conflict, which can override the sense of solidarity. Additionally, women are not inherently peace-promoting. They can act as warmongers and even encourage violent expressions of masculinity. Engaging diverse local actors in the women, peace and security agenda should include examining the challenges and opportunities of integrating grassroots women’s and non-profit sectors’ experiences into the policy agenda.

Measuring success

Several solutions can improve the current reporting and documentation efforts. First, it is important to distinguish between state-led and non-state implementation efforts. While the synergies between state and non-state work on women, peace and security are crucial, governments should not be credited with the work done by civil society actors when in reality they fail to live up to their commitments and should be held accountable for implementing their part of the deal. Diverse interventions on gender equality which do not always correspond to the policy goals are also reported as part of ‘NAP implementation’. Presently, the African Union is implementing the African Continental Results Framework (CRF) as a regional accountability tool. While many countries in 2020 compiled a women, peace and security report ahead of Beijing+25 and Commission on the Status of Women (CSW64), the reports revealed little about concrete policy implementation. As such, CRF is considered a welcome regional initiative.

The lack of robust data systems and poor communication lines with other ministries and CSOs can make reporting inconsistent and challenging. Ministries of gender and women’s affairs often experience competing mandates and shortages of staff, funding and technical expertise. The data from other organizations can be difficult to acquire and interpret. Women, peace and security experts then leverage relationships and alliances to access data. Comprehensive cross-ministerial data management support could address numerous monitoring and information gaps. Additionally, the data collection from non-state actors could involve designated digital platforms and social media communities.

Conclusion

The UNSC has a responsibility to support countries in and emerging from conflict to implement a locally relevant women, peace and security agenda. If elected to the UNSC, Denmark can promote the enhancement of national-level political commitment and accountability on women, peace and security implementation. New institutional channels and spaces could be created by mobilizing the synergies between the existing mechanisms and structures.

This could include further instituting women, peace and security into the UNSC repertoire through quarterly women, peace and security briefings in collaboration with the Informal Experts Group on WPS, Group of Friends of WPS and NGO Working Group on WPS. Such initiatives should also include, subject to shadow reporting from civil society associations, conflict-affected countries alongside troop-contributing countries. Undoubtedly, this would face opposition from some council members. Yet, for the UNSC to support national women, peace and security implementation through its international mandate, it has to ensure regular dialogue and peer exchange regarding gendered insecurities and provide opportunities to present, learn and report back on context-specific women, peace and security advances.

DIIS Eksperter