Roadblock rebels

The Central African Republic (CAR) suffers from a civil war that, after ethnic violence between Muslim and Christian populations in 2013, has settled into a low-intensity conflict in which the country is de facto partitioned. The government, supported by the French and a United Nations mission, control the capital and southwestern portion of the country, while the northeast is under control of a patchwork of Muslim armed groups, allied to mercenaries from neighboring Chad and Sudan.

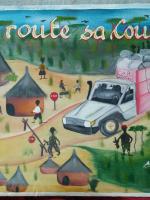

Grievances aside, economic motivations have become central in explaining the behavior of different parties to this complex conflict. The international community emphasizes control over the country’s natural resources (diamond, gold and wood) as a major determinant in the struggle over power. DIIS researcher Peer Schouten holds that this emphasis on natural resources risks blinding us to another important pivot of control. In a progress report published in collaboration with the Belgian conflict mapping organization IPIS (International Peace Information Service), Schouten foregrounds control over trade routes as a central dynamic in the conflict. The point of departure is that it is important to map control over such trade routes, as this control is strategic for the survival of armed groups. Who controls the Central African Republic’s roads can raise taxes, rob people and steer economic activities.

‘Free circulation’ is a common trope in the discursive politics of the CAR. Every rebel faction conjures it as a prime rationale for their armed mobilization; they are fighting for the right to move about freely. But in reality they are not fighting for just anyone’s free circulation, but rather that of their own group. One of the stronger ex-Seleka factions, the UPC of Ali Darass, is an example. He claims to defend the free movement of the peuhl pastoralists, of which he is one. But where he is in control, Peuhl have to contribute to his efforts, giving him either cash or cows in exchange for his roadblocks and armed escorts along dangerous roads. And so it goes for every armed group. Each controls a portion of the country’s strategic routes, a control they defend with all their might. The government is just the same. Supported by the international community, it controls the two most strategic routes in the country: the lifeline that links the capital Bangui to the port of Douala in Cameroon, as well as the Ubangi river, which together supply the capital with all goods and petroleum it needs to keep the government alive.

As a result, mobility, or logistics, is highly militarized across the country. All movement is both armed and a potential prey. The road is a militarized space, and one of the few places in poverty-stricken CAR where money is to be made because valuable goods circulate there. Because profitable routes are so scarce in a country the size of France, it is logical that rebels and the army concentrate around those scarce trade routes, and that many armed confrontations pivot around the question who gets to control the road.

It is in this context that Schouten and IPIS investigate roadblocks, as one of the strategies of parties to the conflict to enrich themselves or simply to survive. In earlier research, we found 20 roadblocks on a 600km stretch of road between Bangui and Bangassou; and on the Ubangi river between Bangui and Mobaye, we found an additional 20 river blocks. In the future, Schouten and IPIS will continue mapping roadblocks and other rebel logistics, to provide empirical grounding to the importance of roads in the political economy of the conflict in CAR.

DIIS Eksperter