How African states voted on Russia’s war in Ukraine at the United Nations – and what it means for the West

Africa’s voting record

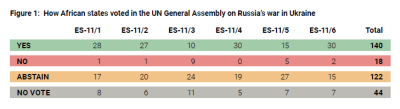

Since March 2022, there have been six major UN General Assembly resolutions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- Resolution ES-11/1 on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine (2 March 2022)

- Resolution ES-11/2 on the humanitarian consequences of Russia’s war in Ukraine (24 March 2022)

- Resolution ES-11/3 on Russia’s suspension from the Human Rights Council (7 April 2022)

- Resolution ES-11/4 on the unlawfulness of Russia’s annexation referenda (30 September 2022)

- Resolution ES-11/5 on the payment of reparations by Russia to Ukraine (14 November 2022)

- Resolution ES-11/6 on a principled and fair peace in Ukraine (23 February 2023)

- Four factors – regime security considerations, economic interests, historically close ties to Moscow, and scepticism towards the West – explain why many African states have not condemned Russia’s war in Ukraine.

- To win more support, Western states should stress the importance of defending the territorial integrity norm as a core principle of international order.

- Pressuring African states to condemn Russia may lead to further alienation.

A breakdown of African states’ voting record reveals several interesting aspects and patterns (see Figure 1). Resolution ES/11-4 – declaring Russia’s annexation of four regions in Ukraine as illegal – received the strongest backing. In total, 30 African states supported it, while 24 abstained or were not present for the vote. No country sided with Russia. This demonstrates the high importance that African states attach to upholding the territorial integrity norm. The reason for that stance is simple. As a result of the colonial era, many borders in Africa do not reflect the ethno-political and cultural identities of people. Thus, many African governments fear that a weakening of the territorial integrity norm may open a Pandora’s box and lead to new territorial conflicts on the continent.

The voting record also shows that resolutions preparing concrete measures to punish Russia have received rather limited support from African states. Only ten voted in favour of resolution ES/11-3 demanding a suspension of Russia from the Human Rights Council. Similarly, only 15 African states backed resolution ES/11-5, which prepares the ground for payment of reparations by Russia to Ukraine.

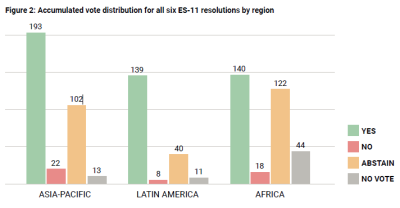

Taken together, a tally of all six ES-11 resolutions shows 140 African votes in favour, 18 votes against, and 166 abstentions or absences. This stands in stark contrast to Latin America and Asia, where most countries have backed resolutions condemning Russia’s invasion (see Figure 2). The fact that a majority of African states have avoided choosing a side in the UN General Assembly was a surprise for many Western observers.

Why many African states have abstained

The reasons why African governments have decided to abstain from Ukraine-related UN resolutions are a little different for each state in the region. Nevertheless, our research suggests that there are four overarching factors that explain the abstentions across the continent. The first relates to considerations of regime security. In recent years, Russia has established close ties to governing elites and key decision-makers in several African countries, including the Central African Republic, Mali, Zimbabwe and Ethiopia. Russia has done so by providing incumbent leaders with diplomatic cover in the UN Security Council, where it holds a veto. For example, in August 2023, Russia vetoed a UN Security Council resolution that would have prolonged the presence of an independent monitoring mission in Mali.

Moreover, Russia has provided governing elites with various forms of security assistance – often through parastatal military companies – against internal rivals and armed insurgents. In this context, it is notable that Russian security assistance has continued despite indications of a military and personnel-related overstretch in Ukraine. In July 2023, for instance, dozens of Wagner fighters arrived in the Central African Republic to secure a controversial constitutional referendum, which, among other things, removed presidential term limits. In short, the governing elites of the abovementioned countries see Moscow as a key ally and protector to secure their hold on power. Accordingly, they are not inclined to jeopardise Russian support by voting in favour of UN resolutions denouncing Moscow’s actions.

A second factor relates to economics and trade. Russia’s economic footprint in Africa is small, accounting for less than three percent of the continent’s total trade with the world. In certain sectors, however, Russia does play an outsized role. For example, a range of African countries rely heavily on imports of Russian wheat, fertilisers, and other agricultural products. In light of rising food prices on the world market, many of these countries seek to avoid provoking Moscow’s ire. The irony is that Russia’s attack on Ukraine and its withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative have contributed, more than anything else, to undermine food security. While many African leaders acknowledge this, they stress that Western-imposed sanctions also contribute to price hikes and supply chain interruptions. For example, speaking at a press conference with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa bitterly complained that ‘bystanders’ are going to ‘suffer from the sanctions that have been imposed against Russia.’

A third factor that influences the diplomatic positioning of African governments is the power of history. During the Cold War, Moscow was an important partner of numerous liberation movements across the continent. To varying degrees, interpersonal and organisational ties are still present today. For instance, Russia enjoys good relations with South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) party, Namibia’s South-West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) party, and the Liberation Front of Mozambique (FRELIMO) party. Moreover, in many African states, large segments of the political elite as well as parts of the public hold positive memories of the Soviet Union’s anti-colonial and anti-imperialist policies. By contrast, the reputation of several European states is tainted by collective memories about colonial abuses. This is an important background factor in explaining why some African governments are hesitant to side with the West.

Fourth, and related to the previous point, there is a widespread perception across the continent that Western states have failed to act in solidarity with Africa in the recent past. An oft-heard example is the West’s failure to support African states during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another is the seemingly inconsistent stance regarding refugees. While Ukrainian refugees have been received with open arms in many European countries (at least immediately after the outbreak of the war), migrants from Africa and the Middle East are treated as a security problem to be

managed. Moreover, not many African leaders share the Western assessment of the Ukraine war as an epochal event that is going to define the future world order. Rather, they see it as yet another armed conflict – just that it is this time in Europe. No doubt, Russia does its best to promote self-serving narratives about the war and to fuel anti-Western sentiments in African countries through disinformation campaigns. But it would be too easy to reduce these viewpoints to Russian propaganda. There is a genuine disenchantment across the continent with what is regarded as Western self-righteousness and double standards. Thus, from the perspective of many African governments, it makes good sense to avoid being drawn into what they essentially perceive as a great-power conflict between Russia on the one side and the United States and its European allies on the other.

How the West should respond

Given that many African governments have adopted a position of deliberate neutrality when it comes to Russia's war in Ukraine, what does this mean for the West?

First of all, while Russia has achieved a lot of traction in Africa, its influence should not be exaggerated. African leaders are not remote-controlled by Moscow. They pursue their own interests and aspirations, which are essential for understanding their diplomatic postures and attendant voting behaviour in the UN General Assembly. Accordingly, the West should not treat African states as pawns in its rivalry with Russia, but as actors in their own right.

Second, Western government officials – in the UN and other diplomatic fora – should stress the importance of defending the territorial integrity norm as a fundamental principle of international order. Given the strong commitment of African states to this norm, such an approach will strike a chord with many leaders and governments on the continent. Thus, norm protection is likely to be a more successful diplomatic strategy than one that is fixated on countering Russia.

Third, Western finger wagging and lecturing needs to be avoided. If anything, it will only deepen the feeling of alienation among African leaders. Similarly, penalising African governments who do not toe the line of the West – by imposing economic and political sanctions, for instance – will at best have a limited effect. Some leaders may change their voting behaviour in response to pressure from the West. But others will be driven away and may even seek closer ties with Russia or, for that matter, China.

Finally, rather than pushing African states to confront Russia, the West should engage with leaders and societal actors on the continent as equal partners. The focus ought to be on areas of common interests including such issues as economic development, digitalisation, public health, food security, and domestic stability. This is of course easier said than done. The point to be stressed here is that disengagement or simple carrot-and-stick methods are unlikely to be successful. In short, the West’s engagement on the continent must be about more than ‘containing’ Russia.