Employment effects of foreign agricultural investments – expectations unfulfilled?

Expectations were high when, a decade ago, a conglomeration of international development agencies, development banks, investment funds and sub-Saharan African governments launched a number of initiatives to promote and facilitate foreign investments in agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. Not only were these initiatives expected to boost agricultural growth in general; many governments also expected them to contribute to meet the objective of creating job opportunities for at least 30% of youth in agricultural value chains.

■ Rebalance policy focus between non-local, including foreign, and local agricultural investments as sources of employment generation.

■ Avoid assessing employment effects only on the basis of gross employment generation in specific investments, as this may conceal employment foregone.

■ Where employment generation is a strong concern, carefully tailor policy instruments to attract investments which, through choice of technology and product, have a proven employment generation capacity.

■ Rethink employment conditions in foreign agricultural investments in order to accommodate the widespread preference for combining employment with own farming among potential employees.

Ten years later, the scant reports that have subsequently been issued from these initiatives indicate that although jobs are being created, the numbers should be counted in tens of thousands rather than in the hundreds of thousands envisaged when the initiatives were launched. Thus, from a policy perspective, there is a need both for international development institutions and for national and local governments to revisit the underlying promises and expectations related to foreign investments in agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa, including that foreign agricultural investments would serve as a vehicle, for instance, to promote employment generation in sub-Saharan Africa.

Foreign agricultural investments and the local context

Foreign agricultural investments only rarely take place in a void. Rather they tend to occur in areas where farming is already widespread, where some of the local farmers offer agricultural employment, often on a day-to-day basis, to individuals from neighbouring households, and where many engage in nonagricultural economic activities as teachers, health workers, shop keepers, bricklayers, carpenters, running transport services, etc. In some cases, foreign investments are made as ‘green field’ investments (in uncultivated land), while in other cases, they involve the acquisition of existing farms, i.e. ‘brown field’ investments.

Thus, to assess the employment effects of foreign agricultural investments in a development perspective, it is important to look beyond gross employment generation and instead examine employment generation in the context of existing employment opportunities, both in terms of quantity and in terms of quality or attractiveness of the employment offered. This, obviously, calls for contextualized assessments. This policy brief reports from such contextualized assessments undertaken in six locations – three in Tanzania and three in Uganda (Map 1) – which since the 2007-2008 food price hikes have received not only foreign, including Danish, but also domestic non-local commercial agricultural investments.

The six locations include cool and population-dense, coffee growing areas as well as warmer and more sparsely populated areas where grain crops such as maize and beans as well as cattle ranging dominate. Combined, the six locations cover an area of a bit more than 11,000 km2, about a quarter of the size of Denmark, and is home to close to 670,000 persons.

Overall, the results show that the employment generation capacity of non-local, including foreign agricultural investments, is limited both in absolute and relative terms compared to that of local, primarily small-scale family farms. They also show that while the employment opportunity offered by non-local agricultural investments is appreciated by some, and seen as an important safety net by others, the majority of the adult population in the six locations deliberately chose not to take such employment, based on a preference for engaging in own farming activities, which only combine with difficulty with the employment conditions offered in foreign agricultural investments.

Neither abundant…..

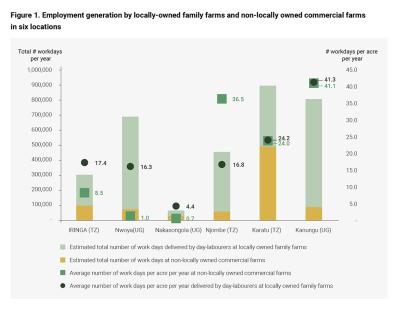

Currently and in absolute terms, the employment offered by locally-owned, primarily smallholder family farms to individuals from neighbouring households substantially outweighs that offered by foreign, including also domestic but non-local commercial farms (illustrated by the stacked columns in Figure 1).

Only in the Karatu location, which for decades has had the presence of significantly-sized foreign-owned, primarily coffee farms, and in the Nakasongola location, which until recently served as an area for seasonal cattle grazing but has now become an area where new farms are established, does the amount of employment offered by non-locally owned commercial farms resemble that offered by locally-owned family farms. This obviously reflects the fact that, again with the exception of Karatu and Nakasongola, in terms of acreage, the locally-owned farms cover a much larger area than the non-locally owned farms.

However, neither the assessment of the employment generation capacity, i.e. employment per acre (=0.4 hectare), of respectively locally-owned family farms and non-locally owned commercial farms (represented by the dots in Figure 1) seems to justify the strong job creation expectations associated with foreign agricultural investments compared to locally-owned family farms. Only in the Njombe location where non-local commercial farms tend to engage in highly labour-demanding crops such as tea and flowers, whereas locally-owned family farms engage in food crops (grain and vegetables), does the employment generation capacity of non-locally owned commercial farms exceed that of locally-owned family farms.

In the mainly grain producing locations (Iringa, Nwoya and Nakasongola) where the choice of technology rather than of crop differs between foreign and locally-owned farms, employment generation per acre at the locally-owned family farms exceeds that of the more mechanized foreign-owned farms. Finally, in the two coffee growing locations where neither crop choice nor technology differ substantially among the locally-owned family farms hiring in labour and the foreign-owned farms, there are great similarities in the figures for employment generation per acre.

…. nor preferred

The preference for taking employment at foreign agricultural investments is limited, and for many it is hard to combine such, often full-time, employment with own farming activities. Across the six locations, only a fraction of the adult population (around five percent) takes employment at farms with foreign or domestic but non-local ownership. Even so, of these five percent, less than one-third describe their decision to take such employment as a – fully or partly – positive choice.

Rather, they describe their decision to take such employment out of necessity, due to a lack of other employment opportunities, including with locally-owned family farms, or due to a lack of land for own farming. Mirroring this, among the vast majority of the adult population of the six locations who do not take employment at commercial farms, this decision is primarily motivated by a preference for being self-employed, including in own farming.

Policy implications

This calls for a significant rebalancing of the policy initiatives aimed to promote the generation of attractive employment opportunities in the agricultural sector in countries like Tanzania and Uganda where family farming constitutes an important source of livelihood. Since the 2007-2008 food price hikes and the renewed international interest in farm investments, e.g. in sub-Saharan Africa, both national and international policy attention has been strongly focused on promoting foreign agricultural investments.

While in some cases such a focus may be justified, policies which favour foreign investments may work to the detriment of locally-owned family farms, and thus to the detriment of an often even stronger source of employment generation than that of foreign agricultural investment. That is the case e.g. when favourable tax exemptions or financial arrangements are negotiated for foreign investors only, or when public investments in infrastructure or in land tenure administration are channelled to facilitate foreign investments, thus creating an unlevelled playing field. Recognising the significant role that locally-owned family farms play in employment generation provides a strong argument for rebalancing this policy focus.

DIIS Eksperter