Power and path dependencies may weaken EU counter-piracy efforts in the Gulf of Guinea

- The invisible characteristics of the EU’s counter-piracy infrastructure must be extensively mapped to expose elements of activity duplication and unequal distribution of resources.

- The EU must be innovative and adaptive in addressing potential path dependencies that result from its resource flows to the region.

- EU counter-piracy activities must be designed and constantly reshaped through dialogue and collaboration with regional partners.

In 2013, West African coastal states in the Gulf of Guinea region (extending from Senegal in the north to Angola in the south) signed the Yaoundé Code of Conduct to combat maritime crime. The code promoted a trend of increasing donor activity intended to sustain the resulting Yaoundé Architecture (which includes the code, a declaration and a memorandum of understanding between regional organisations), through capacity-building and counter-piracy operations (see Box 1).

A decade later, piracy in the Gulf of Guinea grew increasingly urgent as the world’s hotspot of attacks, and questions remain about whether the Yaoundé Architecture (YA) is fit for purpose.

EU support to the Yaoundé Architecture

As a regional bloc with significant socio-economic interests tied to the Gulf of Guinea, the European Union (EU) emerged as a critical supporter of the YA.

On 25 June 2013, Gulf of Guinea states gathered in Cameroun’s capital Yaoundé to sign a flagship agreement that would change the course of counter-piracy efforts in the region. The agreement, called the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, established a region-wide security architecture that would facilitate information sharing and coordinated law enforcement across West and Central Africa.

The code also fostered international cooperation with coastal states by providing a maritime security infrastructure through which international partners could support the region. This was further propelled by the adoption of two UN Security Council Resolutions at the time, encouraging regional and international actors to collaborate around creating maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea.

Support included the training of naval authorities to combat maritime crime through operations at sea, implementing maritime security strategies in maritime-related security and law enforcement agencies on land and establishing information-sharing centres to strengthen maritime domain awareness.

To ensure the sustainability of the Yaoundé Architecture, over-arching policy fora were formed to facilitate continued dialogue on progress, needs and solutions in the region.

Since 2015, the EU has facilitated resource flows to address maritime insecurity in the region. It has spent over €92 million on nine different programmes and initiatives across the region, intended to strengthen regional cooperation and information sharing, enhance maritime domain awareness capabilities, and contribute to the effective rule of law through legal reform. More than €65 million of this total is channelled to programmes that specifically address piracy and armed robbery at sea.

In 2021, the EU rolled out its Coordinated Maritime Presences concept – a flexible tool which allows the EU to use existing naval and air assets of member states in the region to share information, analysis and awareness in support of counter-piracy operations.

Despite the millions of euros spent by the EU to support the YA in the decade since its establishment, maritime crime in the Gulf of Guinea remains a major security challenge. Identifying successes and shortcomings of the EU’s counter-piracy support may provide a first step in retooling and reshaping the YA as an effective counter-piracy framework.

To this end, comparing EU counter-piracy activities in the Gulf of Guinea to the image of a large-scale infrastructure project can provide guidance.

The counter-piracy infrastructure

Infrastructure can be described as systems that support the effective functioning of society. It facilitates the circulation of people, goods, ideas and other valuable resources on a global and local scale. It is also characterised by both material and non-material flows – think of not only railways and water pipes but also SWIFT banking and the internet.

The materiality and non-materiality of infrastructure has a logic of both visibility and invisibility: some resource flows are easy to recognise, while others remain hidden. This is relevant to the EU as a counter-piracy actor in the Gulf of Guinea, because its actions in the region rely on both.

Visible infrastructures include port facilities, patrol vessels, maritime monitoring and surveillance systems. Invisible infrastructures are less tangible. They include, for instance, flows of funding to specific areas of the YA, transfer of certain expertise, and the relative weight and attention given to specific maritime crimes.

Material flows in the infrastructure may dominate because they are more readily visible. They can therefore prevent a sensitivity towards the invisible flows within the same network, for instance, the dynamics around how problems and solutions are defined and the deeper power dynamics in the relationship between donor and recipient.

Bringing to light these non-material or invisible dimensions can be a powerful driver in assessing the efficacy and sustainability of counter-piracy efforts. Employing this lens, two central characteristics are particularly instructive in assessing EU counter-piracy efforts: power distribution and path-dependent systems.

1. Power distribution

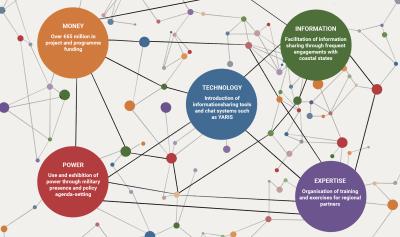

Mapping the EU’s counter-piracy programmes and activities in the Gulf of Guinea as an infrastructure highlights the various flows of, for example, money, technology, information, expertise and power to combat piracy in the region. As depicted in Figure 1, notable examples of each of these flows exist. Beyond the millions of euros in counter-piracy investments by the EU, projects such as the Gulf of Guinea Inter-regional Network (GoGIN) led to the adoption of useful tools and technologies within the region, such as the Yaoundé Architecture Regional Information Sharing Network (YARIS), for enhancing maritime domain awareness.

Frequent engagements with Gulf of Guinea states, both within the framework of the EU’s activities and through multilateral fora such as the G7++ Friends of the Gulf of Guinea plenaries, have facilitated information flows from the EU to the region. In terms of expertise flows, capacity-building initiatives such as those conducted in cooperation with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s Global Maritime Crime Programme have centred on building counter-piracy judicial and prosecutorial capacity amongst member states.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of power flows is the EU’s expansion of counter-piracy efforts into the dimensions of defence and diplomacy. The Coordinated Maritime Presences, which facilitates the use and exhibition of European military power in the Gulf of Guinea, has been criticised by regional observers as an example of neo-colonialism.

2. Path-dependent systems

EU counter-piracy efforts rely on pre-established structures and past practices or actions. This makes them inherently resistant to change, thus continuously consolidating into path-dependent systems. Under the YA, path dependencies are evidenced by the strong focus on maritime regulation and enforcement, without regard for the root causes of piracy. Issues like maritime domain awareness, for example, are left invisible in the infrastructure, and therefore remain unaddressed. Another example is the multiplicity of actors, donors and capacity-building programmes within the YA, which risks overlap and duplication of efforts. It also means that funding flows may be skewed towards sustaining certain parts of the YA over others.

The EU’s activities in the region not only shape but are also shaped by the logic of the YA. This implies that inherent flaws within the YA may generate similar flaws in the counter-piracy infrastructure of the EU within the region. The EU may therefore reproduce both the intended and unintended effects of the YA.

Way forward

Assessing EU activities in the Gulf of Guinea through the lens of infrastructure exposes potential successes and shortcomings. As one of the region’s largest maritime security providers, these intricate dynamics between the EU and the Gulf of Guinea should be fully explored, and successes and shortcomings better understood if the YA is to function effectively. Findings apply not only to the EU. They may also be extended to the YA and other similar contexts.

Thus EU counter-piracy efforts must be designed and constantly reshaped through dialogue and collaboration with regional partners. This will have a dual positive effect: first, it is likely to result in a greater balance of power (and less fear amongst regional actors of hidden neo-colonialist agendas); and second, it will ensure that interventions are shaped by an understanding of regional undercurrents and underlying causes, and not merely by EU interests and priorities in the region – a pragmatic shift that is necessary if security in the region is to be sustained in the long run.

Further, the invisible characteristics of the EU’s counter-piracy infrastructure must be extensively mapped to expose elements of activity duplication and unequal distribution of resources. For both the EU and Gulf of Guinea states, the potency of visibility may also help develop notions of shared interests, progress, functionality and effectiveness in addressing piracy in the region.

Finally, the EU should employ tools of innovation and adaptability to address potential path dependencies that result from its various resource flows to the region. Research and best practices can play a crucial role in ensuring that the EU is primed to embrace rapid advancements in technology and potent alternatives, even when heavy investments are made along existing trajectories.

Sections of this policy brief were written as part of the project ‘Counter-piracy Infrastructures in the Gulf of Guinea’ (COPIGoG), kindly funded by a Grant from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, administered by the Danida Fellowship Centre.

DIIS Eksperter