When armies enforce the law

- Understanding the role of the Ghana Armed Forces in internal security requires an understanding of the political development of Ghana as a country during and after the colonial era.

- A clearer division of labour between the police and armed forces is unlikely, given the history of civil-military relations in Ghana specifically, and West Africa more broadly.

- The considerable political pressure to deploy the Ghana Armed Forces internally is combined with pressure from individual soldiers and their families, due to the advantages reaped from doing so.

The Ghana Armed Forces play a significant role in domestic security. To fully comprehend how and why requires a deeper understanding of the way that individual, local, national and regional factors interact. A blurring of the duties of the police and armed forces speaks to a never fully realized separation of who oversees internal and external security.

The division of labour between a police force that deals with domestic security concerns and armed forces that defend the borders of a country against external threats has become a generally accepted ideal during the past 150 years. In practice, this separation has been historically tenuous, which was emphasized when the Cold War came to an end, and new security threats such as civil wars and international terrorism emerged.

The terrorist attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001 strongly reinforced pressures towards the development of expeditionary security capabilities, which was done partially by expanding the roles and responsibilities of the armed forces in internal security.

In Ghana, these international transformations in the role of the armed forces together with the country’s particular history of civil-military relations have led to an expansive set of functions for the Ghana Armed Forces domestically. Today, the armed forces play a consistent role in internal security operations, sometimes referred to in public debates as ‘internal peacekeeping’. Military personnel are deployed to deal with a wide range of law enforcement matters across the country, such as illegal mining, illegal logging, armed robberies (patrolling), and chieftaincy disputes.

Blurred lines

Since Ghana was first declared a republic in 1960, the military has played an intimate role in the country’s political life. This is part of a larger pattern of military involvement in politics in West Africa that has the highest rate of coups on the continent. For example, the Nigerian Armed Forces were in power until the late 1990s and the army ran Sierra Leone in different formations during the war that engulfed the country in 1991-2002.

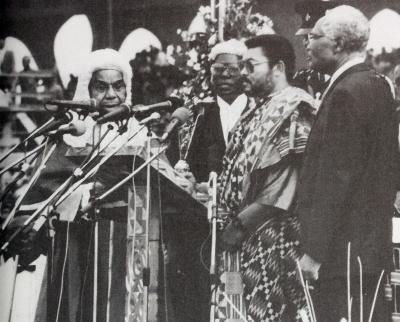

Most recently, in 2021, the militaries of Mali and Guinea have successfully carried out coups. From the mid-1960s until the early 1980s five military coups took place in Ghana, culminating in Jerry Rawlings, a flight lieutenant, leading a group of junior officers to power in 1981. Rawlings headed a military government until January 1993 when the Fourth Republic was announced and as a civilian, he won the democratic elections as the head of the National Democratic Congress, remaining in power until 2001.

Over time, our police has lacked capacity in many ways. He doesn’t know how to shoot, nobody fears him, he can’t enforce the law, he is somewhat stale. The military came and filled that gap.

The fact that Ghana was ruled by the military, or a president with a military background, for more than 30 years has led to a blurring of civilian and military roles in Ghanaian politics. This period saw a normalization of a broadened set of domestic responsibilities for the armed forces that were exposed and consolidated by Rawlings’s seamless transition from military to civilian leader.

Despite obvious differences — one is, of course, illegal, while the other falls within the constitution — there is one important similarity between military coups and the deployment of the military to deal with internal security matters: they both reflect the never fully institutionalized separation of military and civilian domains. This colonial legacy has translated into weak oversight and contributed to corruption.

Colonial administrations typically organised and mandated African security forces around regime preservation, that is, to protect executive offices and strategic resources as well as to control and suppress individuals and groups perceived to be a threat to the status quo. In turn, this has meant that as a democratic governance system was re-introduced in Ghana in 1993, after more than 25 years of military rule, the newly elected politicians did not seek to insulate themselves – and the civilian sphere – from the armed forces and keep them in check. On the contrary, politicians saw and continue to see soldiers as constituting one among many instruments of enforcing domestic security at their disposal.

Politicized police

Resorting to the deployment of military force internally is partially defined in negative terms, because it reflects the Ghana Police Service’s limited authority and legitimacy in the eyes of the Ghanaian public. It is widely emphasized among observers and scholars on Ghana that an underlying sense of mistrust characterises police-public relations, which can be explained by four factors:

First, the militarised and regime-preserving policing practices that were established during the colonial era in Ghana have been inherited and continued by the governments that have come after independence.

Second, the Ghana Police Service’s struggles with underfunding have resulted in limitations on equipment, such as means of transportation, a general inability to serve the public broadly speaking, and widespread corruption.

Third, the police are notoriously partisan, meaning that they always serve the party in power, and therefore are mistrusted by the opposition. This is in large part a consequence of the Inspector-General of Police being appointed by the president.

Fourth, the police organization is shaped by neo-patrimonial practices, what is often referred to as corruption, and political interference. Recruitment into the police is a good example, as currently it is close to impossible to become a police officer without political backing.

Because the Ghana Armed Forces are seen as more neutral, better equipped and trained, but also more robust and aggressive, politicians who want to appear resolute, tough on crime, and responsive to security challenges across Ghana prefer to deploy the military over police officers. Combined with underfunding, politicisation and a history of limited public legitimacy, this has weakened the Ghana Police Service and contributed to a self-reinforcing situation where the Ghana Armed Forces are generally seen as the more reliable security actor.

Pressures from within the armed forces

Pressures to deploy soldiers for internal operations also come from within the armed forces rank and file. On one level, soldiers will push to be sent on operations outside their own units – ‘even if they don’t go to do anything,’ as one former security adviser to the government noted in an interview.

On all operations, soldiers will receive an allowance and are fed, which cuts down the financial burden at home in the barracks. There are additional benefits that may be accrued from deploying with internal security operations, namely engaging in the illegal activities that their very presence is meant to prevent. This has left them open to the same accusations of corruption that have weakened the police’s authority, and concerns among military officers that they are heading down the same path.

Finally, there is pressure from within the family unit itself. Just as in the case of international peace-keeping, there is social pressure to go on operation. ‘The soldiers will want to continue to go; the wives are all interested in who is given these opportunities,’ one interviewee noted, because it generates – and saves – resources.

In sum, there are multiple pressures on soldiers to engage in internal security operations, including a personal interest to do so. Combined with the direct and indirect structural pressures on the Ghana Armed Forces, such social pressures contribute to why it is ‘very easy to enter and difficult to exit’ internal security operations, as the security adviser quoted above noted.

I do see a direct link with internal security operations, it is basically the same thing we go and do in international peacekeeping.

International peacekeeping

On one level, internal security operations and international peacekeeping both provide arenas that ‘help [soldiers] to build their own capacity’, as one officer noted. Because the Ghana Armed Forces have never engaged in prolonged warfighting to defend Ghana’s borders, the main experience of the armed forces is from these two types of activity. And there is a striking similarity between them in terms of roles played, as routine patrolling and reconnaissance, protecting dignitaries (politicians, traditional leaders) and civilians, liaising with local state and non-state authorities, and guarding are central to both.

It is because of these similarities that international peacekeeping and internal security operations have been mutually reinforcing. On the one hand, the Ghana Armed Forces have deployed in peacekeeping roles that resemble law enforcement; this in turn has redefined the role of the armed forces somewhat and facilitated its position in domestic security roles. On the other hand, their performance domestically prepares soldiers for the role that they will play abroad.

In this regard, peacekeeping is part of a wide set of historical, political and social factors that have shaped the space in which the Ghana Armed Forces have become a central player in internal security operations.

This policy brief is an output from the research programme Domestic Security Implications of Peacekeeping in Ghana (D-SIP), funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and supported by the Danish Fellowship Centre.

DIIS Eksperter