Post-Liberal Visions: Memory, Virility, and Geopolitics on the French New Right

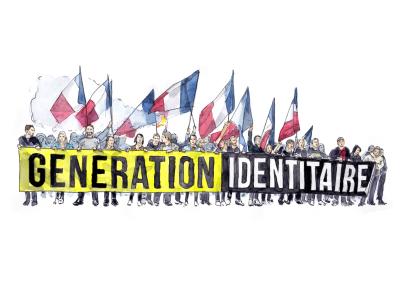

In 2013, the French far-Right group Génération Identitaire uploaded a YouTube video labeled “A Declaration of War from the Youth of France.”

In the video, a dozen young men and women address the camera head on. They claim to be the generation of “ethnic fracture,” “anti-white racism,” and “imposed cultural intermixing” – and add: “Don’t think this is a simple manifesto, it’s a declaration of war! The Lambda painted on proud Spartan shields is our symbol.” The group promises not only war but memory war: “We reject your history books and redefine our memory.”

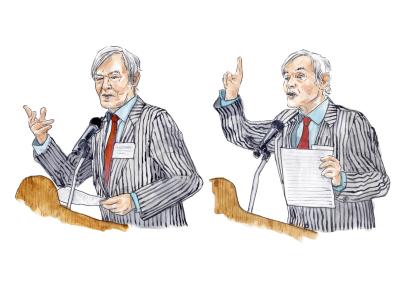

Five years down the line, the neo-Spartan warmongers have the wind in their sails, no longer easily dismissed as a bunch of lunatics. Since 2013, Génération Identitaire has morphed into a transnational movement with branches in a host of countries spanning the US, UK, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Italy, Hungary, Scotland, and many more. In that same period, their anti-immigrant slogans have moved from the fringes of national policies to the agendas of presidents, prime ministers, and far-Right luminaries all over Euro- America. It is hardly a coincidence that the Identitarian movement took off in France, though. If we sift through the current infatuation with anti-liberal ideas, France appears a vibrant epicenter. Génération Identitaire explicitly refers to the French “New Right” (nr) or Nouvelle Droite, an intellectual movement that appeared in 1968. Today its leading figures – Alain de Benoist, the late Guillaume Faye, and others – stand out as intellectual signposts for a broader transnational trend which I term the “disruptive far-Right.”

This disruptive far-Right stands in contrast to more traditional conservative movements. The French new right explicitly brands themselves as “new” in contrast to more traditional French far-Right thinkers – figures like Chateaubriand, Maurras, and Barrès – who advocate Catholicism, monarchism, and the French soil. Against a conservative nostalgia for a prerevolutionary past, Faye and de Benoist hope to embrace a post-liberal future. For that larger agenda of subverting the America-centric world order that was imposed on Europe after 1945, they consider the nostalgia of the traditional far-Right unfit.

Against a conservative nostalgia for a prerevolutionary past, Faye and de Benoist hope to embrace a post-liberal future. For that larger agenda of subverting the America-centric world order that was imposed on Europe after 1945, they consider the nostalgia of the traditional far-Right unfit

Although the traditional, Catholic Right is regaining ground in France with Marion Maréchal’s establishment of an academic college in 2018, the international influence of this intellectual movement does not yet compare with that of the New Right.

The French New Right, and the ethos of subversion which informs it, has substantial transnational ramifications. Russian philosopher Aleksandr Dugin – whose geopolitical doctrine of “Eurasianism” has supposedly inspired Putin – shares longstanding ties with de Benoist who, as Dugin puts it, is “the foremost intellectual in Europe today” new right writings and ideas are increasingly translated and disseminated through militant networks, journals, blogs, and social media, and by way of far-Right publishing houses across the world (Bar-On 2011). Indeed, one observer claims, Faye’s Why We Fight – a call to whites to unite against the “colonization” of Europe by non-whites – is now read so widely as to have “become the lit- erary cri de coeur for right-wing nationalists all over the world” (Kennedy 2016). It is also noteworthy that both Faye and de Benoist pop up regularly in alt-Right and pro-Trump digital forums (Collins 2016) where their work is promoted by American white nationalists; they have even appeared in person at a number of US white natio- nalist events, including Jared Taylor’s annual American Renaissance conference and Richard Spencer’s National Policy Institute. nr out- looks, in other words, seem increasingly to capture the zeitgeist and, irrespective of any direct influence, to rhyme with broader Western anti-immigration sentiment, praise for strongmen, and yearnings for renewed virility and geopolitics.

At the heart of the French new right – and again, in synch with broader transnational trends – sits a profound contempt for the liberal inter-national order. Even if the new right is sometimes at odds with political far-Right parties and movements of today (the Rassemblement National in France for instance, is red-hot nationalist while the new right is very critical of the modern nation state), the disruption sought by the nr is first and foremost directed at the project of liberal internationalism and driven by a visceral anti-Americanism.

This chapter makes a foray into the new rights anti-liberal contempt and to its alternate vision of virile antagonism and imperial geopolitics. In so doing, the chapter explores the ways in which the French nr plugs into broader French and Western lineages of remembering and narrating the twentieth century. The post-1945 world order was sustained by a particular kind of liberal memory – a memory that justified a liberal ethos of self-restraint and binding international cooperation in the post-war period. Not only does the new right, like its far-Right peers, reject that memory in its ambition to subvert the post-1945 liberal order. As we shall see below, it also suggests a very different take on the functions and use of historical memory as such.

The thinkers of the French new right are convinced that the liberal age is drawing to a close. Inspired by theories of catastrophe from René Thom to Ilya Prigogine, Faye claims that the West is currently living a “convergence of catastrophes” – immigration, ecological disaster, and so on – that will lead to an imminent collapse “somewhere between 2010 and 2020”. To some, the twilight of liberalism sounds like a doom and gloom scenario, but to the new right, it heralds a new and promising beginning. Whether one laments or applauds the imminent cataclysm is intricately linked to one’s conception of the twentieth century: the nr and its sympathizers are at odds with the long-dominant liberal version.

To the new right, however, the world order that emerged from the ashes of 1945 was not a civilizational peak but a grievous decline: a pacified, depoliticized globe where all diversities and contradictions were overcome

World War II and the deep trauma of the Holocaust are crucial moments in liberal memory that was constructed in the aftermath of the two world wars. The experience of war and tyranny in the first half of the twentieth century led to a deep-felt plus jamais ca! a resounding “Never Again.”

The specific version of liberalism that materialized after 1945 was a “liberalism of fear” that was first and foremost about avoiding: avoiding war, pain, tyranny, and fascism. To the new right, however, the world order that emerged from the ashes of 1945 was not a civilizational peak but a grievous decline: a pacified, depoliticized globe where all diversities and contradictions were overcome. To them, the liberal world order was nothing other than an American world order, giving way to a “totalitarian” (sic), homogeneous, globalized maelstrom of the market: savage capitalism, vulgar consumerism, and political correctness at the level of thought (Champetier and de Benoist 1999). This visceral discomfort with the post-1945 Pax Americana has deep resonance in a French context, where post- war politicians were still preoccupied with the rang de la France. A liberalism of fear, self-restraint, and international governance never had a deep draught in France, where Charles de Gaulle’s “certain idea of France” implied that France was too exceptional to be bound by international institutions that were merely a cover-up for American domination.

When Paris was liberated in August 1944, de Gaulle made a speech expressing zero gratitude for the American, Canadian, British or other lives that were lost on the beaches of Normandy: “Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France!” This was memory politics with a vengeance. De Gaulle’s nationalist rhetoric turned out to be merely the harbinger of a thinly veiled anti-Americanism that was to permeate French foreign policy during the Cold War: rapprochement with the Soviet Union, distance from nato, and veto against the UK’s entry into the eec because it was America’s “Trojan horse” in Europe.

Charles de Gaulle - the grand figure of French politics after World War II - wasn't keen on the cultural and political domination the US exerted in Europe after the war

The new right plugs into this pervasive anti-Americanism and yet their hostility is different. It is not just geopolitical or preoccupied with “eternal France,” but puts forth a broader cultural, social, and philosophical critique of the homogenizing effects of American capitalism and its way of life. Echoing contemporary American neoconserva-tives and their observation that the liberal project ultimately led to “flabby, prosperous, self-satisfied, inward-looking, weak-willed states whose grandest project was nothing more heroic than the creation of the Common Market,” the new right views the liberal end state as a world devoid of greatness and heroism. Yet American neoconservatives still support the liberal order, despite its defects, while the new right wants to do away with it altogether.

the new right views the liberal end state as a world devoid of greatness and heroism

Since 1945, defending anti-liberal opinions anywhere in the West has not been an easy feat: due to the vigour of liberal memory, such far-Right positions are instantly tainted with the memory of “fas- cism,” ‘‘racism,” “Nazism,” and “anti-Semitism.” In France, however, the post-war “Never Again” slogan was primarily about war and tyranny; not about the Holocaust. “In retrospect, it is the universal character of the neglect that is most striking. The Holocaust of the Jews was put out of mind “[...] one of many things that people wanted to forget” (Judt 2010, 808). Or, according to Enzenberger, “In the fat years after the war [...] Europeans took shelter behind a collective amnesia.”

In France, that collective amnesia has a name – “the Vichy syndrome” – which refers to the deliberate “forgetting” of the dark years when the Vichy regime collaborated with Nazi Germany and helped deport French Jews (Rousso 1987). But French memory politics has evolved. Since the 1960s, the Holocaust has step by step made its way into liberal memory in France, where it has become the object of debate and controversy. To deny or belittle the Holocaust today is, as Judt points out, “to place your- self beyond the pale of civilized public discourse”.

Despite this predicament, de Benoist has to grapple with the Holocaust head on to enable his critique of the liberal world order. De Benoist is by no means a Holocaust denier and disavows the founder of the Front National, Jean-Marie le Pen, who claimed that the gas chambers were merely a “detail in history.”

Nevertheless, de Benoist starts his disruption of liberal memory by stressing that it is memory; not history. “Memory” is memory politics; a narrative constructed for political purposes, in this case to uphold the moribund liberal order, in contrast to “history,” which is the outcome of scientific inquiry, critique, and free thinking. Memory “is not about truth but about loyalty”.

In line with other revisionist historians, de Benoist relativizes the importance of the Holocaust and suggests that it was not a unique case of metaphysical Evil but a horrendous act on a par with other forms of human suffering.

The entire World War II with its long cortège of disasters and dramas, massacres and deaths of all kinds is boiled down to the horrendous anti-Jewish persecution. This event becomes the key event of contemporary history, if not of human history as such

“The entire World War II with its long cortège of disasters and dramas, massacres and deaths of all kinds is boiled down to the horrendous anti-Jewish persecution. This event becomes the key event of contemporary history, if not of human history as such” (de Benoist 1994, 12). Although the Holocaust was horrific, human history is punctuated by pain and evil and it therefore does not make sense to “establish a dreadful hierarchy of suffering”.

The horrors that occurred under Stalin were just as bad but did not – according to de Benoist – fit into liberal memory. As the liberal democracies had allied themselves with one totalitarianism to fight another, “the two totalitarianisms cannot be compared since in that case the justification of the world order that emerged out of the 1945 victory would collapse”.

De Benoist not only debunks the sacrosanct status of the Holocaust but also the liberal interpretation of the twentieth century as an evolution from “madness to prudence” and from tyranny to freedom. In contrast to liberal memory that sets World War II center stage, de Benoist suggests that the most significant event of the twentieth century was World War I. It was World War I that introduced all the elements that came to fruition after 1945: the rule of law in international relations (Wilson’s Fourteen Points), the end of empires (the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian ones), and the moral, ideological war. World War I was a rupture and decline which marked the transition from war as a noble and regulated confrontation between armies, animated by a gentlemanly spirit, to a moral if not metaphysical confrontation between good and evil in which one party can claim to fight a legal war against a barbaric subhuman enemy who is the incarnation of absolute evil.

Transposing the historical center of gravity from the second to the first world war, in other words – and presenting the two wars as basically of the same nature – de Benoist destabilizes liberal memory and minimizes the significance of the Holocaust, which he considers to be the responsibility of one crazy lunatic. The Holocaust had nothing to do with racism: the Jews “were not at all killed in the name of biological inequality! They were killed in the name of the crazy dream of a certain Adolf Hitler”.

Beyond the liberal order: revitalizing masculinity, virility, and war

The critique of liberal memory was merely a first step in the attack on the liberal world order and liberal societies. In contrast to a peace-loving, security focused, comfort-seeking liberalism, the think- ers of the new right seek to restore “conflict” and “politics.” This does not mean a gung-ho praise of war as such, nor does it mean that they are against peace. What the new right opposes is the liberal idea of perpetual peace, or pacifism. They believe that war and conflict cannot – and shall not – be eradicated. Peace is not the original condition of man, but a situation obtained through war. All peaceful polities are the outcome of war, the liberal world order being no exception.

This recovery of agonism requires a restoration of the Spartan virtues of discipline, heroism, and virility – a trend which resonates well with broader calls for masculinity across the far- and alt-Right political landscape today

This critique of liberal peace is clearly underpinned by Carl Schmitt’s notion of “the political” as a distinction between friends and enemies. Man is a political animal and would “no longer be man, if he was no longer political”.

But this recovery of agonism requires a restoration of the Spartan virtues of discipline, heroism, and virility – a trend which resonates well with broader calls for masculinity across the far- and alt-Right political landscape today.

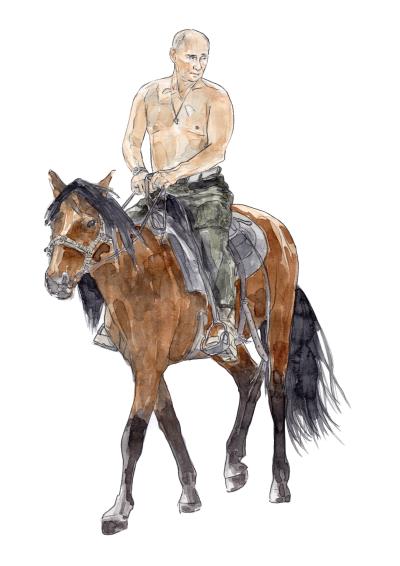

It is no coincidence that Vladimir Putin has become an icon of hypermasculinity and “macho-politics,” posing bare-chested in several official photos. This call for virility, however, has little to do with intensifying Western military spending or “technological edge.” The nr thinkers are not preoccupied with military strength per se. To them, technological war – ushered in during World War I – is a decline from limited, non-ideological combat in which real men, animated by a chivalresque ethos, fight face to face.

Their preoccupation with strength is about (the decline of) masculinity. In their view, the agonistic phenomena of politics, war, and conflict are intimately linked to virility in contrast to the soft, fluid spheres of economy and consumption. The liberal attempt to swallow up agonis- tic politics in the vortex of international law and the market has gone hand in hand with a broader trend of “feminization.” According to de Benoist, the liberal pacification of “polytheistic” values was enabled by a feminism that has run amok, entailing a loss of male virtues such as virility, discipline, and heroism. In the words of Faye – who finds Western men less manly than Muslims and Africans – “Europe is in a process of devirilization” (Faye 2000, 6).

This reading of European history is inspired by the Italian fas- cist thinker Julius Evola, who has become a luminary for disruptive far-Right intellectuals. To Evola, the process of feminization is not only a feature of post-1945 liberalism but of modernity as such: a modernity that has coincided with the rise of “gynecocratic” values and “increased domination of the feminine pole of being over the masculine one” (de Benoist 2007, 8). In Benoist’s words, modern lib- eral society is “fatherless” and narcissistic, giving priority to economy over politics, consumption over production, discussion over decision, dialogue over authority – a society of victimization, therapy, and end- less psychological debriefing. In late modernity, even war – the male domain par excellence – has become feminized: fluid, asymmetrical, and without a clear beginning or end. The current use of drones in Western warfare stands as the epitome of such feminization.

Geopolitics, ethno-pluralism, and a “europe of 100 flags”

The post-liberal order not only sounds the death knell of feminized pacifism but also calls for a new nomos of the earth: a new international order. To de Benoist, the liberal world order is first and foremost an American world order: “the main enemy is, on the economic level, capitalism and the market society [...] and on the geopolitical front, America”.

Seen through new right spectacles, the “unipolar moment” of hegemonic US power was an all-time low where the geopolitical enemy – America – could finally reign supreme over a potentially “depoliticized” world. The main question to de Benoist is therefore whether there is an alternative to US military and cultural hegemony: “Unity or plurality of the world, universe or ‘pluriverse’, homogeneous globalization or globalization according to the diver- sity of cultures and peoples” .

To break free from American hegemony and pave the way for a new plurality of empires and cultures, de Benoist and Faye agree that Europe should pivot to Russia

To pursue that move, de Benoist – once again taking his cue from Schmitt and his distinction between land and sea powers – seeks to bring the “geo” back into geo-politics. In other words: to replace the fluid (and feminized) American world order with the solidity and fixity of the earth. In contrast to the US and Britain, both sea powers and trading nations, continental Europe embodies earth power par excellence. This “earth” though, has nothing to do with the territory of the modern sovereign state. To Schmitt, the partitioning of planetary space will not in the future divide the globe into territorial states but into “Great Spaces,” which he envisions as larger political and geographical units of regional or continental scope.

To break free from American hegemony and pave the way for a new plurality of empires and cultures, de Benoist and Faye agree that Europe should pivot to Russia, but they have different notions of what such a pivot might entail.

Faye envisions a Euro-Siberian Federation from “Brest to the Bering strait” (Faye, 2010). In his view, Europe must turn to Russia because the major geopolitical fault line today is not the one between East and West but that between North and South, the main security threat to Europe being “colonization” from the South.

The role model for this new European empire is not the German Reich, which was built on a specific nation (or race), but the Roman Empire, with its manifold “multicultural” provinces

To erect a bulwark against rampant Muslim immigration, a post-liberal Europe must go hand in hand with white Christian Russia (the prominence of the theme of “colonization” in Faye’s thought probably also explains why he recently adopted a more conciliatory attitude to America and Christianity). Confronted with the virility of the South, countries in the North must unite. Faye’s Euro-Siberian utopia is not only a hierarchical polity but also presupposes a return to small, self-sufficient, ethnically pure enclaves.

To de Benoist, in contrast, the over-arching aim of a European empire, including Russia, remains to oppose the liberal globalitarism of the Anglo-American sea powers. The role model for this new European empire is not the German Reich, which was built on a specific nation (or race), but the Roman Empire, with its manifold “multicultural” provinces. The empire is to be not a magnified version of the modern nation-state defined by a territory and a Volk but “a spiritual or politico-legal idea” (de Benoist 1993, 3). Not a material entity defined by a “national interest,” but a polity that is “animated by a spiritual fervor. Without this fervor, it would merely be the outcome of violence – imperialism – a mechanical superstructure without a soul” (de Benoist 1993, 5).

Finally, the empire which de Benoist hopes to restore is an “area of civilization.” De Benoist’s civilization is far from homogeneous, and not necessarily based on religion. Indo-European civilization – spanning a territory from the Atlantic to India – is a mosaic of various religions, cultures, languages: a federation of organic com- munities with large degrees of autonomy. It is not a colonial empire, which would presuppose the conquest or inclusion of people from other “areas of civilization.” This idea of a re-spiritualized Europe is, of course, far from the current EU – an institution deliberately established by its liberal architects as a grey and technocratic con- struction. It is also something very different from the current French republic, and what de Benoist considers the cultural suicide of its “melting pot” ideal. The Europe of de Benoist’s dreams is a patchwork of local cultures and legal systems: a “Europe of 100 flags” allowing each ethnic, cultural entity to flourish.

Conclusion

In a recent issue, the American journal Telos suggests that “Across the West, the old liberal center is coming apart and the extremes are resurgent” (Pabst 2017). These rumors of liberalism’s imminent collapse are probably exaggerated, but the tectonic plates of the global political landscape are definitely shifting. This essay provides a glimpse into some ideas integral to the French new right and elucidates its critique of liberal politics and its vision of an alternate global future. What are the most crucial points to be drawn from that glimpse?

First of all, that France and French political thought is key to the development of transnational far-Right, and that this is so for a number of historical reasons. To begin with, the post-war liberal proj- ect of self-restraint and deliberate impotency never had deep roots in France. The French founding fathers of the European Coal and Steel Community, Robert Schuman and Jean Monnet, envisioned a supranational institution that was to end centuries of war and power politics in Europe.

But the idea of a European cooperation that could stifle French sovereignty met stiff opposition from de Gaulle and the Gaullists who were to define French foreign policy during the Cold War and beyond. De Gaulle was skeptical about post-1945 interna- tional institutions. To prevent future wars in Europe, he preferred to conclude a bilateral agreement with a weakened Germany that was divided into two and no longer a military power. The idea of deliberate French impotency was not within de Gaulle’s comprehension, nor was the post-fascist appreciation of uncharismatic leadership. The current French constitution that was tailormade to fit “the general” installs a strong president elected directly by the people, and de Gaulle himself had a predilection for so-called bains de foule – crowd-mingling – that allowed him to reenact his direct relationship with the French people.

To them, the artificial construction of the modern nationstates went hand in hand with the oppression of the real multicultural Europe, an ethnic pluriversum of vibrant, organic cultures spanning the Mediterranean, the Nordic cult of Odin, the cultures of Basques, Bretons, Laplanders, Siberians, and many more who, despite differences, share a common pagan, Indo-European ethnos

Secondly, that the new far-Right is not necessarily nationalist. The glimpse into French new right thinking provided in this chapter warns against easy labels and reductive analysis. It is true that the current surge of far-Right movements is often seen as a return to nationalism. For instance, the French political party, le Rassemblement National, is EU-hostile and subscribes to the slogan of “préférence nationale,” which echoes Donald Trump’s “America first” or “make America great again.” But the new right is not in favor of a parochial form of nationalism and has no intention of defending le rang de la France – a stance that is echoed by far-Right thinkers elsewhere.

This has to do with the nature of their anti-liberalism, which is ultimately anti-modern. That de Benoist and Faye are “anti-modern” means that they have a pronounced aversion for the nation-state. To them, the artificial construction of the modern nationstates went hand in hand with the oppression of the real multicultural Europe, an ethnic pluriversum of vibrant, organic cultures spanning the Mediterranean, the Nordic cult of Odin, the cultures of Basques, Bretons, Laplanders, Siberians, and many more who, despite differences, share a common pagan, Indo-European ethnos, if not a common purpose.

This, then, is perhaps the French new rights most important contribution to current developments: its clever rephrasing of identity and pluralism in ways which avoid invoking the memory of Holocaust, genocide, and racism. De Benoist’s concept of “identity” performs a rhetorical stunt, elegantly replacing the uncomfortable associations of the term “race.”

Insisting that there is no hierarchy between different cultures or identities, de Benoist can claim to equally “respect the destiny of the sometimes afflicted Innuits, Tibetans, Amazonians, Pygmies, Kanaks, Aborigines, Berbers, Saharans, Indians, Nubians, the inevitable Palestinians, and the little green men from outer space,” and simulta- neously insist that these “Others” should stay apart and at distance from Europe.

At a time when the question of migration is high on the political agenda everywhere, he and his French new right peers would seem to have delivered a most crucial piece of intellectual and rhetorical ammunition to new r voices everywhere, struggling to escape the no-goes of their post-45, post-Holocaightust, post-segregation past: “racism” and “white supremacism.”'

Will this continuous undermining of the old liberal order give way to a new geopolitical arena where might is right, authoritarian men strike deals, and cultures throw off the shackles of binding agreements and institutions?

Seen from the perspective of the old liberal order, the foreign policy of a Donald Trump may appear unpredictable, dependent upon the whims and tweets of the day. But seen through a new right looking-glass it makes a remarkable amount of sense: the constant, ostentatious disruption of “feminized” if not “feminist” liberal institutions personified by Merkel, Mogherini, Macron, or Trudeau; the EU a “foe”; NATO “obsolete”; multilateral agreements and institutions betrayed by the hour.

Will this continuous undermining of the old liberal order give way to a new geopolitical arena where might is right, authoritarian men strike deals, and cultures throw off the shackles of binding agreements and institutions? The French new right, sharing de Gaulle’s ambiguous stance towards the liberal world order as well as his preference for strong leadership, stands right in the midst of this revolt. At this historical moment, when liberal memory is waning, the ideas of the new right have become essential to the broader political climate.

Beyond a liberalism of fear and restraint, a new confident authoritarianism is rearing its head, giving rise not only to a budding Identitarian movement but to a larger far-Right vision of global order.

This essay is an adopted version of a chapter in the book Geopolitical Amnesia: The Rise of the Right and the Crisis of Liberal Memory published by McGill Queens University Press. An interview with editor Vibeke Schou Tjalve and contributor Louise Riis Andersen can be read here.