Barry and me

Part of my research work for the “World of the Right” project is to look at the origins of contemporary right-wing populism. In the given American context, no politician’s legacy has been surrounded by as much lore and speculation as Senator Barry Goldwater, the 1964 Republican candidate for President, who many consider the father of modern-day American conservatism. In the United States, what’s known as the “Goldwater effect” remains contentious, either extolled, decried or excused, never more so in the wake of the election of Donald Trump.

Sometimes the best way to get to know someone is to get a sense of their adversaries. In Goldwater’s case, the person who stands out as his leading antagonist might just be Nelson Rockefeller, who is forever linked to him as both men competed for the Republican nomination in 1964. A bellwether moment not just for the heart and soul of the American Right, but for US politics in general. So before heading out to Goldwater Country, the high mesas and open deserts of Arizona, I started my research trip in New York, home of the Rockefeller Archive Center.

The relics of Rockefeller republicanism

Today, “Rockefeller republican” denotes a form of liberal republicanism and is bandied about as the worst kind of epithet in conservative circles. They constitute what can be described as an endangered species on the Right, who long before the advent of the Trump administration, were labeled “RINOs”, Republicans in Name Only. But once you enter the Rockefeller archives, a former mansion on the grounds of the leafy Rockefeller estate, you are transported to a lost civilization that politically in America once thrived like Atlantis. There you find the bones and ruin of a civic-minded republicanism that Nelson Rockefeller proudly personified, which very much led the machinery of the Republican Party between the Second World War and 1964, arguably the highpoint of Pax Americana.

Pragmatic and open-minded, Rockefeller republicans were, however, fanatical on one key point. Their unbending commitment to the standards and norms of moderation, which is why, beyond differences over such political questions as the government’s role in society or issues dealing with US foreign policy, Goldwater’s influence on the Right represented an existential threat.

To appreciate how the Rockefeller republicans perceived Goldwater, rather than read his best-selling book, the “Conscience of a Conservative” you may be better served by checking out his autobiography, “With No Apologies” a rather contrarian title considering its alleged conservative source. No wonder, then, they pilloried him as a dangerous radical, as Burke once warned of the Jacobins in Revolutionary France. This point is buoyed by Goldwater's famous quote at the 1964 Republican convention, “extremism in defense of liberty is no vice”, which Rockefeller and others interpreted as giving cover to right-wing extremists such as the John Birch Society and the Ku Klux Klan.

Goldwater’s advocacy for “states’ rights”, moreover, outraged those Republicans who saw themselves as the Party of Lincoln. By voting against the Civil Rights Act in 1964, on which he claimed his opposition to be solely based on constitutional grounds, Goldwater’s ascent was a tipping point in US politics as the Republican Party transformed into the party of the American South. With the “Southern Strategy” settled, Goldwater set a foundation for political success later enjoyed by Nixon, Reagan and ultimately Trump.

“Barbarians about a campfire”

Within the Rockefeller collection, document after document, Goldwater is cast as the lead villain impeding Nelson’s White House ambitions, not due to his politics per se, but because he is a harbinger of things to come, the “politics of emotion.” At the same time, I should point out that I was left with this hostile impression of Goldwater after wading through the Graham Molitor papers.

This matters because Molitor was a consultant hired specifically by Rockefeller to produce one of the most comprehensive dossiers on any opposing political candidate. This meant shining a light on Goldwater’s personal life, on his alleged nervous breakdown, on his marriage troubles, and anything else unsavory that Rockefeller could use against him in the fight for the Republican nomination. Ironically, this sort of scrutiny backfired as the Right turned further against Rockefeller in part because of his own marital issues. At any rate, Rockefeller’s hatchet work may have as much lasting effect in fostering the toxicity of today’s American political scene as Barry Goldwater’s reputed brand of conservatism.

In the end, to the shock of many outside observers, Rockefeller lost the Republican nomination to Goldwater. Mercilessly booed on the convention floor, Rockefeller ignited the wrath of the Goldwaterites. Norman Mailer, recalling the episode years later, said they resembled “barbarians about a campfire.” As a Rockefeller, it is not a surprise that for the Goldwater-faithful Nelson represented everything that was wrong with post-war Republicans. Too elite, too effete and most importantly, too liberal. A real mouthful, but no exaggeration as it is the only way to explain the waves of thinking which fueled Goldwater’s path to power, just as it did for Donald Trump fifty-two years later.

What’s funny though is that Goldwater came from a family that was in many respects the Arizonan version of the Rockefellers. Not as fabulously wealthy, but the Goldwater name carried and continues to carry a great deal of prestige in Arizona, a state they helped establish, while at same time building a very successful retail business. Despite his “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” image, Goldwater, personally, never shied away from his cushy background proclaiming, “I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth and I intend to keep it that way.”

Departing from New York with a clearer picture of things, I continued on my research trip, landing at the Barry Goldwater Terminal of Phoenix’s Sky Harbor International Airport. On arrival, my first port of call was the town of Prescott, the former capital of Arizona, which Barry himself called home. Goldwater’s uncle had served as an 11 time mayor in Prescott and it is here that Barry kicked off his Republican presidential campaign in 1964. Something that John McCain, another Arizona senator, would replicate during his own ill-fated presidential campaign in 2008.

An Arizonan Republican, as the joke goes, may be the most redundant term in American politics. In Prescott these days, Republicans tend to tilt heavily towards Trump. As the midterm elections approach, political placards blanket the town, many displaying the acronym #MAGA (Make America Great Again), like incumbent Congressman Paul Gosar’s, a view which compelled six of his siblings to publicly disavow him and support his opponent. Democratic candidates (they do exist), on the other hand, are politically savvy enough to run towards the center, referring to themselves as a “pragmatic Democrat” or “independently-minded Democrat.” Waving your liberal credentials is no vote winner in Prescott.

My first stop in town was the Sharlot Hall archives. There, I learned more about how the Goldwater family came to settle Arizona. Originally of Jewish extraction hailing from northern Poland, they became well practiced refugees. First escaping Czarist pogroms, they made their way to France, then to London and finally arrived in the US, but via the Central American country of Nicaragua, a point of origin that I reckon would surprise many today on the American Right.

The migratory path of the Goldwaters as immigrants and refugees is interesting when considering the way in which the political debate on immigration, as in Europe, is being shaped by those on the Right. Here, Goldwater differs mightily from his modern day conservative brethren in that he was fascinated with all things Latin America, spoke Spanish fluently, and let’s not forget that the Hispanic’s community’s support in Arizona was always an instrumental part of Goldwater’s political success.

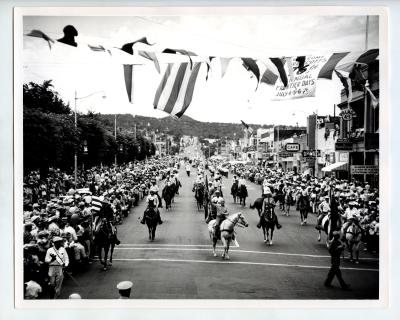

I also checked out materials and ephemera covering that memorable day in 1964 when Goldwater commenced his campaign. The Senator rode horseback down to the town square wearing jeans and cowboy hat and led a parade in his honor. It’s a day that is remembered as fondly as when Hollywood came to town to film the Steve McQueen rodeo movie, Junior Bonner. Prescott, after all, is home to the world’s “oldest Rodeo”, something the locals won’t let you forget.

What caught my attention about Goldwater’s visit, though, was one particularly unsettling anecdote in a local periodical I found. Apparently on the same day, a rumor had swept through town about “black militants” coming to Prescott with the aim of disrupting Goldwater’s parade. Their pending arrival never materialized because, well, it was the summer of 1964. Before the Black Panthers, before the likes of Stokely Carmichael ever reached the national stage. It seems to me that to be labeled a black militant in the town’s mind meant simply a person who was an advocate of the Civil Rights Movement. Though I would not peg Goldwater as a racist, it’s difficult to deny what his critics say, that racial overtones were never too far away from his campaign, which by association casts a dark cloud over his legacy.

A serious man

Leaving Prescott, I drove by the old Goldwater department store and Goldwater Lake, before heading down Black Canyon Highway to Phoenix. I was on my way to see Barry Goldwater’s personal papers, housed at Arizona State University, and as you can guess, ASU is not too far away from Goldwater Boulevard and Goldwater Park.

On my arrival, sun-soaked students zipped around from class to class on motorized scooters and banana skateboards, provided to them by courtesy of the university. Not having the time, nor the courage to partake in such escapades, I met the head archivist at the school’s library and there stacks of boxes encompassing Goldwater’s entire life were waiting for me. Leafing through the first few pages of my opening document and finding a letter from none other than William F. Buckley, one of the leading intellectual lights of the American conservative movement, as a historian, I knew I was in for a treat.

The papers showed that Goldwater was no mealy-mouthed politician, a point on which everyone agrees, nor was he a bombastic knuckle dragger as he was characterized by many of his most severe critics. The papers show him to be erudite, yet never pretentious. He was serious-minded but with a charming capacity for whimsy. Attesting to his catholic tastes, he was a keen aviator, a ham radio enthusiast and one of the world’s foremost collectors of Hopi Katsina dolls. Although stout in his conservatism, he was by no means dogmatic. Bullish and blunt, Goldwater in the final tally comes across as a sensitive and thoughtful man. But what about the 27 million across the country who had voted for him for president?

There is a disconnect between the two that makes me think of what Rick Perlstein, the scholar of American conservatism, observed shortly after Trump’s election. By analyzing the subject as a serious intellectual proposition, he admits that he overlooked and diminished the part played by the downright bizarre and profane fringe elements of the movement that lived closer to the Right’s center than he realized.

Of course, it would be remiss of me to pigeon-hole all of Goldwater’s followers and the activists backing him. Many of those people and groups were as passionate, independent of mind and intellectually stimulating as Goldwater himself. But collectively, reading through the correspondence a pattern began to emerge in which Goldwater’s support tends to be either sycophantic or equally, plain irate when the senator veers from their own perception of him. Denouncing him as a “Democratic stooge” during the Watergate investigation was commonplace, for instance, just as upbraiding him for not being conservative enough when he backed the moderate Gerald Ford over Ronald Reagan in 1976.

As another example of this ongoing trend, later in 1993, Goldwater, the then octogenarian retired senator, due to his uncompromising support for gays in the military, generated the most despicable hate mail he had yet to receive during his long career. For this perceived heresy many Republicans at the time sought to cast Goldwater out of the party altogether.

The full conclusion of my research trip will come later as the “World of the Right” project unfolds and I dig deeper into the material. My early impression upon leaving Arizona is that if Goldwater and Trump do align, it is not wholly the common ground of their politics and personality, but rather the common ground of their base of support. The same unblinking fervency of the Goldwater phenomenon that scared the Rockefeller republicans so much circa 1964 is the same powerful force that frightens their modern-day equivalents, the shrinking “Never Trumpers” who sit uncomfortably on the American Right in 2018.