Migration on the intimate stage of marriage

Migration is most often depicted as frozen moments in time: migrants scaling border fences, clinging to capsized boats or waiting in line at immigration authorities in Europe. These moments are pivotal to document the perils of high-risk migration – but to fully understand the circumstances and choices that lead to migration – and the consequences of migrating – we need to follow the lives of migrants over the course of time.

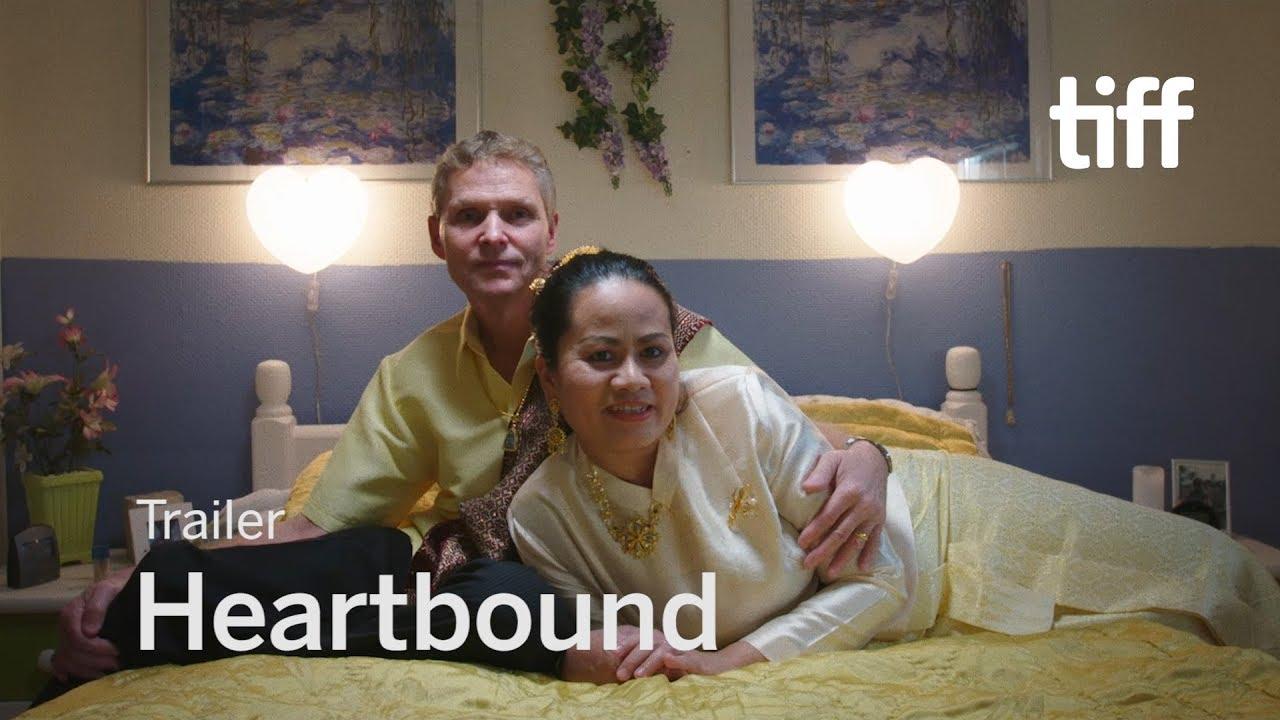

The rural Danish region of Thy is home to more than 900 Thai women. 25 years ago, there were none – except Sommai, who met Niels when she was a sex worker in Pattaya, married him and moved in with him in Thy. Ever since, she has arranged marriages between women from her home village in Isaan in northeastern Thailand and Danish men.

In the new documentary film ‘Heartbound’, we witness life as it plays out for these Thai-Danish couples over the course of ten years. Shot both in Thy and in Thailand, the film is a mirror-image story that shows how destinies in these two diametrically opposite places unfold. The film, made by DIIS senior researcher Sine Plambech and director Janus Metz, is also a document of anthropological research on the mechanisms and long-term consequences of migration.

The FKK-Sapere Aude project "Women, Sex & Migration: Seeing Sex Work Migration and Human Trafficking from the Global South" (2016-19) is based on case studies and ethnographic fieldwork in Thailand and Nigeria – two of the countries where many women migrating independently to Europe come from. Heartbound focuses on the Thai case of the research project.

Thai women began migrating to Europe primarily via marriage and short-term sex work migration in the late 1990s. Through remittances they financed houses, education and healthcare at home. Nigerian women, by contrast, began migrating to Europe a decade later. Facing increased migration control, they resorted to undocumented high-risk migration through the Sahara Desert, across the Mediterranean, finding work in the European sex industry.

Female breadwinners half a world away

The research behind Heartbound is funded by Sine Plambech’s FKK-Sapere Aude project “Women, Sex & Migration: Seeing Sex Work Migration and Human Trafficking from the Global South”. The project shines light on the interconnectedness of women’s migration, human trafficking and sex work migration as it relates to EU’s increasing migration restrictions.

In 2003, Sine Plambech visited the Thai migrant women in Thy for the first time. Three years later, when she and Janus Metz started filming the lives of transnational migrant families, Sommai had found a husband for Kae from her village. Ten years later, Kae is a cleaning worker in Thy, sending remittances to her family in Thailand. In Heartbound, Sommai and her husband Niels are visiting Sommai’s home village in which she has built a large brick house paid for with the money she has earned by working in a fish factory in Denmark.

These scenes from Heartbound emphasize that the women who migrate to Denmark contribute to economic prosperity in their home villages. Often, the migrant families in north-eastern Thai villages can afford to build houses, pay for healthcare and education through the money sent by the daughters, mothers or sisters in Europe.

While there is no precise data on Thai women’s remittances specifically, data from the World Bank show that remittance payments to Thailand have increased significantly in the past ten years, and in most countries in Europe, 85 percent of Thai immigrants are women. Worldwide, women constitute slightly less than half of migrants, and migration of women from the Global South to Europe is commonly understood as part of a broader global feminization of migration (domestic workers, marriage migrants and sex workers) where a particular burden is put on women to ensure development and the well-being of families in the Global South through migration. However, the significance of gender plays out in a multitude of ways. The need for female migrant breadwinners increases when male breadwinners lose their job as day labourers, become sick and can’t afford medication or struggle with alcohol or drug addiction.

Research-based documentaries like Heartbound reach much wider audiences than academic papers.

At the same time,statistics show that academic articles are read by fewer and fewer people.

Rather than continuing to argue against this development, I think we need to accept it, while we insist that there are multiple ways in which we as researchers can bring our research to use while not jeopardizing the quality of the research, Sine Plambech writes in this DIIS Comment.

However, migrating in search of a better future for themselves and their children is not without consequences for the Thai women. In Heartbound, Kae travels back to her village in Thailand, after being married to Danish Kjeld, to talk to her 12-year-old son Mark who does not understand why the family can’t stay in Thailand. Eventually, he joins Kae and Kjeld in Denmark, goes to cookery school and moves to Copenhagen to pursue a career as a chef.

Sommai, who has been living in Denmark with Niels for 27 years, feels torn between Denmark and her home country. She doesn’t want to die in Denmark, and Niels does not want to live in Thailand. Love, deprivation and longing are also causes and effects of migration.

Restrictions lead to risky migration

One of the key findings of Sine Plambech’s research project is that stricter migration laws don’t discourage migrants from travelling, but instead entail riskier forms of migration.

In the beginning of Heartbound, 22-year-old Saeng asks Sommai to help her find a Danish man to marry. However, because of Denmark’s 24-year rule, Saeng can’t migrate through marriage yet. Instead, she travels to Pattaya and starts working in the sex industry. Eventually, she marries a Finnish man and moves to Finland with him. As such her migration is not hindered, but rerouted and prolonged through a riskier route – the sex industry in Pattaya, before she eventually reaches Finland.

One scene shows the particular pain and heartbreak that migrant mothers face. Saeng is speaking with her mother over Facetime from Finland. Her two sons now live with their grandmother, but Saeng discusses the idea of only seeking family reunification for her youngest son – she fears that the oldest son has lived in Thailand for too long to be able to start a new life in Finland. Her efforts to create a better life for her children eventually leads to them being separated.

Another woman from the village, Lom, who has been working in the sex industry since she left school after 9th grade, returns home to her village to take care of her ailing mother. Her father complains that Lom isn’t contributing enough to the family’s economy working in their rice paddies, so when her mother passes away, Lom travels back to Pattaya to work in the go-go bars selling sex to European tourists. For these women, both marriage migration and sex work are ways of improving life for their families and for future generations.

RISK

One of the key findings of the project is that stricter migration laws don’t discourage migrants from travelling, but instead entail more, specifically gendered, and indebted forms of high-risk types of migration.The project effectively documents the interconnection of stricter migration laws to riskier migration for female migrants, and how this relates to some of the women ending up in situation of human trafficking and exploitation.

In areas that have depended on migration for survival, such as Edo State in Nigeria and Isaan in Thailand, the women and their families migrate in more risk-filled ways. They borrow more money for the journey, which then has to be paid off in Europe, before they can start sending money back. This means than more and more female migrants from both Thailand and Nigeria turn to the sex industry. In Heartbound, this is depicted when two young Thai women, Lom and Saeng, migrate to Pattaya to become sex workers to send back remits to their families in Isaan.

A consequence not described in the film is that a lot of Thai women end up working in brothels in Denmark and in the rest of Europe in order to make money fast. The deeper underground a woman lives, for example working alone in a brothel, the more she earns.

DEBT

Migrants take ever greater risks to release themselves or their families from the clutches of debt. Female migrants acquire more and more debt in order to migrate to Europe to make money to send back to their families. Entire debt industries profit of this, and the women often take new loans to pay off old ones. The stricter the EU border laws become, the more money the women have to borrow to make the journey to the north, and the longer and harder they have to work to pay it off. The question of debt is deeply connected to questions of cash flow and access to banks and state guaranteed loans for day labourers, unemployed people and women in the Global South. The project recommends more focus on the bank sector as a part of migration polices, as debt produces migration.

MIGRATION REDUCES MIGRATION

The project documents how migrant women are able to lift their families out of poverty and debt when given access to stable and legal labour markets, thereby reducingthe number of family members migrating to Europe.

In one of the final scenes of Heartbound, Kae, who migrated to Denmark 10 years ago to marry Kjeld, sits with her now grown son Mark at a train station, waiting to send him off to his new life in Copenhagen. Because Kae migrated, her children don't have to. Mark will never have to leave his future children with his parents in order to find employment in other countries.

News, reviews and interviews on 'Heartbound'

- Love in a cold climate (The Nation)

- Is the key to happiness a daughter in Europe? (The Isaan Record)

- TIFF review (5 stars)

- Review by hammer to nail

In Danish:

Heartbound is funded by The Danish Film Institute, DR, European Council - Eurimages,The Swedish Film Institute, Netherland’s Film Fund and Production Incentive, Nordisk Film & TV Fund and VPRO.

It had its world premiere at Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), North Americas largest film festival, to much critical acclaim. It is selected for a long range of international festivals and has been awarded the 'Best Feature' by the American Anthropological Association. It will have theatrical release and will be shown on TV in Denmark (DR1) and across Europe.