Fortifying the EU’s eastern border countering hybrid attacks from Belarus

Since August 2021, the EU-Belarusian border has been subject to approximately 50,000 illegal border-crossing attempts. The unprecedented influx, organised by the Belarusian authorities, weaponised immigrant groups from MENA countries to destabilise the EU, resulting in 8,000 illegal immigrants entering the EU. The situation on the Belarusian side of the border metamorphosed into a humanitarian crisis that has claimed multiple lives. Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland (with 173, 679, and 418 kilometres of border respectively) found themselves at the forefront of these hybrid attacks. They introduced extraordinary measures, including both technological and physical barriers, to protect their borders with Belarus, and hence the EU’s eastern border.

- Surveillance technology plays an essential role in securing the EU’s border with Belarus

- Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland emphasise the need for physical barriers in addition to surveillance technology to secure the border with Belarus

- Erecting physical barriers at external borders goes against the EU’s preference for democratic dialogue and cooperation

- While EU member states remain divided over their support for physical barriers, EU agencies provide administrative help to bordering states

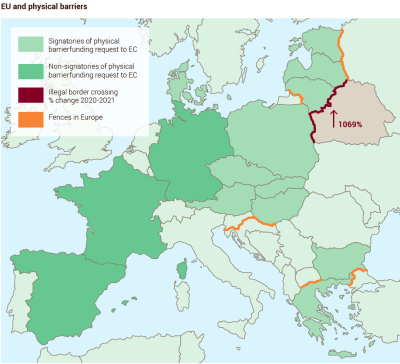

This approach is consistent throughout most of the EU’s eastern enlargement states, while standing in sharp contrast to the EU’s official “diplomacy over fences” policy, with certain exceptions, such as Denmark, which sent 15 km of barbed wire to Lithuania. The Member States remain divided with regards to support for fences on external borders, as erecting physical barriers undermines long-cherished European ideals of shaping the EU’s neighbourhood through democratic means. Moreover, the EU’s external border surveillance is a less regulated element of land border control that remains fragmented and leaves gaps in the common border protection protocol. This results in incoherent surveillance and funding policy on external border protection as well as divided support for the use of physical barriers.

Between 2005 and 2017, the EU implemented integrated surveillance and control systems at its external eastern border, installing cameras, thermal imaging equipment, radar, infrared barriers, microwave sensors, and sensor cables. The operation was focused on guarding the Russian border, and primarily designed to fend off contraband. Following the post-election political crisis in Belarus in 2020 and the orchestrated migration crisis in 2021, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland urgently extended their national investments for border protection. Latvia is considering permanent fence implementation by 2024. Lithuania has committed to erecting both technological and physical barriers on the Belarusian border by September 2022, while Poland plans to install electronic surveillance along its entire external land border (with Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine) as part of its recently adopted Uniformed Services Modernisation Programme for 2022-2025.

The virtual barrier: surveillance technology at play

Consisting of a wide range of modern surveillance technologies, the virtual barrier, constitutes a more preventive rather than confrontational measure. Usage details and locations of specific technologies employed along the EU-Belarusian border remain undisclosed for security reasons. Detection of border violation systems, including stationary and mobile technical equipment, play a key role. Perimetric surveillance detects and identifies objects within the border protection zone, transmitting alarms to the control centre. Such technology includes continuous surveillance equipment: seismic ground sensors with their own power supply and data transmission systems, as well as special detection cables that can be installed on surveillance towers and fences to detect e.g., attempts at scaling, cutting and undercutting the wall.

This is supplemented with re-deployable technologies, notably optoelectronics, which are used for video verification of alarm signals, such as advanced thermal and motion sensors that identify and differentiate movements, infrared systems for restricted light areas and degraded weather conditions, as well as standard and night-vision cameras. All data is transmitted to control centres, which are responsible for the evaluation of, and appropriate response to, the situation at hand. The data are processed using a specialised control software that analyses the visuals in real-time and identifies border crossing patterns. Archiving and analysis of data on such violations are vital for informational exchange between Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland to improve the regional security response.

Portable technical equipment assigned to border guards and patrol officers is used for quick response operations, and is especially important when no clear patterns are displayed. Thereby, body-cams, mobile thermovisors and radars, multimedia messaging service (MMS) cameras, standard and night-vision binoculars, as well as more mundane equipment, such as speakers, torches, etc. are essential. Optoelectronic devices are also integrated into new patrol vehicles.

Typically, they are equipped with thermal imaging technology that can trace movement within a 6 km radius and radar that facilitates tracking people within an 11 km range and cars within 20 km. Technical border protection is also provided by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), such as the “FlyEye” UAV platform, that is used in the airspace to monitor the border and carry out search flights. Border guards also use different types of drones in operational and reconnaissance activities, e.g., to follow up on and monitor the activities previously detected by motion sensors. Anti-drone equipment, such as portable cannon-type guns that enable catching drones “from the other side” is of equal importance.

Some of the technological solutions employed at the EU-Belarusian border to deter illegal immigrants have taken less conventional forms. For instance, in 2018-2021, Latvia was part of the EU’s trial programme “iBorderCtrl” that tested AI-powered lie detectors scanning migrants’ faces to verify statements’ reliability. Loud announcements in different languages (including Kurdish and Sorani dialects, Arabic, English, French, and Russian) have been played at the border zones of all three countries, informing people that crossing the border illegally is subject to criminal liability. Additionally, Poland sent out automated text messages to immigrants approaching the border: “The Polish border is sealed. BLR authorities told you lies. Go back to Minsk!”

Erecting the physical barrier: fences and barbed wire

The European Commission has repeatedly stated that it will not finance fences. However, countries bordering Belarus insist on the necessity of physical barriers alongside technological solutions to protect the EU’s eastern border, despite restricting possibilities of democratic dialogue with the eastern neighbourhood.

In 2021, after unsuccessful attempts to access EU funds for physical barrier construction, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland proceeded with national funds allocation instead. To respond to the escalation at the border, Latvian authorities installed a temporary barrier: 37 km of barbed wire rolls and 22.8 km of fence in the most vulnerable areas. The country is also considering erecting a permanent fence of 130 km by 2024. In August 2021, the Lithuanian government allocated EUR 152M for 500 km of physical barrier on its border with Belarus to be finalised by September 2022. In October 2021, the Polish parliament approved PLN 1.6 B (EUR 352M) for a 5.5 m high technology-enhanced wall that will cover approximately half the length of Poland’s border with Belarus (186 km) by June 2022, while the electronic barrier will extend along the entire border.

National border authorities highlight that physical barriers restrict manoeuvring space and ensure additional time for border guards to respond to violations, thereby helping to prevent border crossings in general. It is stressed that the physical barrier will be used in combination with surveillance systems to produce the desired effects, as the barrier itself is a purely preventative measure. While illegal crossing attempts to Lithuania and Poland have plateaued, the Latvian border is under intensified pressure. The local border guards speculate that immigrant flow was diverted after unsuccessful attempts to cross the increasingly fenced-up Lithuanian and Polish borders. In locations where the physical fence and surveillance systems are fully integrated, no violations have been recorded. Until the modern surveillance equipment and the physical barrier are finalised across the perimeter, their precise effect cannot be evaluated and the border area must be protected physically. Long-term, the barriers are expected to decrease the need for physical monitoring, as the operations will be carried out from the control centers, thereby decreasing the overall costs.

The EU’s reserved response

Managerial assistance provided by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), including asylum procedures, illegal border-crossing registrations etc., played a significant role in dealing with the consequences of the illegal immigrant influx in all three countries. Upon request, Frontex also provided on-site support such as standing corps officers deployed in Lithuania and Latvia. To counter the hybrid attacks on the Lithuanian-Belarusian border, the Rapid Border Intervention operation also included operational experts as well as technical assistance: 30 patrol cars and two helicopters. Furthermore, Lithuania and Latvia acquired interpreter assistance due to the lack of an Arabic-speaking population.

Other EU institutions also came into play, contributing to the overall support of over 200 EU agency staff. The European Commission allocated EUR 360M to cover Border Management and Visa Instruments across the three countries, with an available top-up of EUR 200M for 2021 and 2022. Furthermore, the Commission proposed evoking Article 78(3), covering temporary legal and practical measures for asylum and return, for the Council’s adoption. Although the Commission firmly refused to fund any physical infrastructure – with exceptions for surveillance towers and previously funded control posts – technology as a means of security stands central here. The Internal Security Fund, Frontex, and individual member state funds forefront technology to secure the EU-Belarusian border. Europol has strengthened its cyber-surveillance by flagging data related to illegal border-crossings from Belarus. Furthermore, security measures were tightened within the EU in an attempt to control illegal migration within the Union.

The EU’s restrained response owes much to internal contestation regarding the means by which its external boundaries should be drawn. Thereby, the EU’s support has thus far been framed by assistance for technological border management solutions and migration management systems. Meanwhile Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland continue to advocate for measures combining both new technologies and physical barriers to efficiently guard the EU’s border.

DIIS Experts