Decolonising academic collaboration

In September 2021, researchers from Kenya, Ghana and Denmark, working together in three multi-year collaborative research programs funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, met to discuss the inequality inherent in their collaborations. Following from this conversation, this brief explores the nature and implications of inequality in North-South collaborations while also suggesting some immediate steps that could be taken to address inequalities.

- The process of decolonising academic collaboration should be led by research institutions in the South. Northern funding agencies and researchers should support this endeavour without dominating it.

- Northern funding agencies should support broader South-driven regional and international initiatives that seek to address decolonisation and strengthen South-driven knowledge production.

- COVID-19 has reinforced approaches that centre on “remote fieldwork.” These approaches must be careful not to reproduce inequalities where Southern researchers end up as data producers and “fixers” for Northern researchers or contribute analytical insights without full recognition in research outputs, e.g., as co-authors.

- Funders in the North should ensure that the geographical scope of funding allows South-based researchers to also conduct development research in and on the North.

The nature of inequality in academia

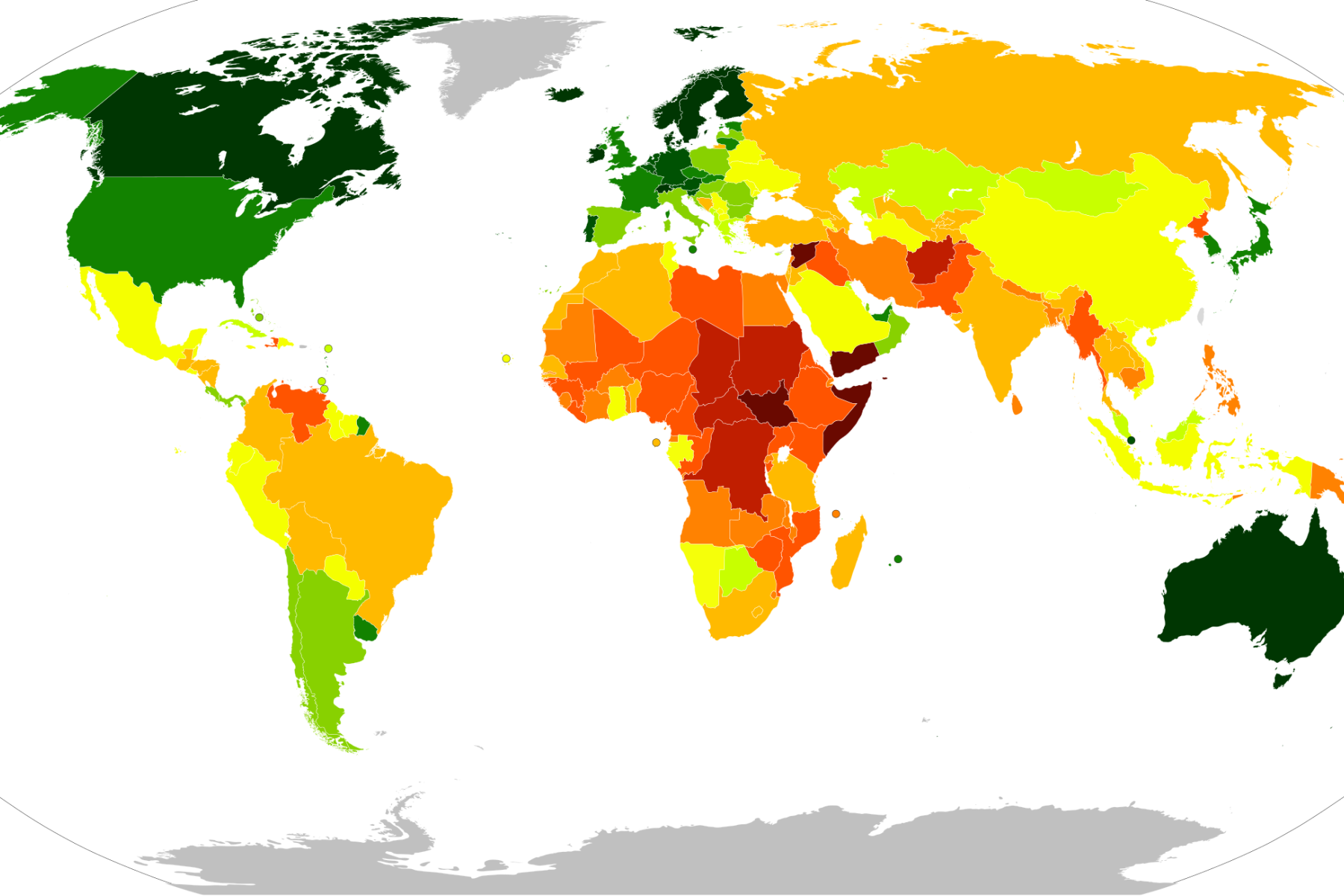

Structural biases in academia are the product of lopsided power relations. They have historical roots in colonial legacies but are perpetuated by contemporary dynamics of inequalities between South and North. Financial support for research projects usually comes from donor agencies in the North. Consequently, it is often Northern research institutions that define the focus of research and set the agenda on which methodological and theoretical approaches to apply. The reluctance of many African governments to invest consistently in the production of academic knowledge compounds this bias.

Inequalities are further consolidated by an uneven North-South balance in academic publishing where reward systems favour publication in high-ranking journals with a global reach. Most academic journals, however, were founded in and continue to be managed from Europe and North America and are dominated by Western academics and perspectives. African universities have limited access to these journals – and thereby to the production of this dominant body of work in global academic knowledge.

“Why do we still depend on the North to drive agendas that we need to drive? In the last two months we have run seminars on decolonising knowledge. [However,] if we look at how partnerships are built, there are a lot of researchers [in Africa] that work closer with Northern than African researchers.”

The consequences of inequalities in academic collaboration

When research projects are defined in the North, there is a significant risk that the production of knowledge does not reflect the interests and perspectives of academics and stakeholders in African countries. Research results may furthermore be irrelevant or miss vital points because the framing, methodologies, and analysis of research projects and findings overlook key aspects of the local context and people’s lived experiences.

Moreover, when projects are defined by researchers in the North an implicit hierarchy emerges within them, where the knowledge and publications of North-based researchers end up dominating the process. By default, this perpetuates inequalities.

A frequent outcome of North-driven projects is that researchers in African countries end up mainly as the collectors or providers of data, and on-the-ground “fixers” for Northern academics. In its most problematic (but not uncommon) form this leads to data grabbing where African researchers collect empirical data, sometimes in highly dangerous circumstances, and may even carry out parts of the analysis – yet are not recognised as co-authors.

These issues are particularly important at the current time when academics based in the North seek to develop methods for “remote fieldwork” in response to COVID-19 and high-risk security situations. Ideally, such efforts provide an opportunity to review and reconfigure inequalities in research collaborations. However, if poorly conceived they can turn into North-led data extraction mechanisms which reinforce inequalities and racial hierarchies.

Who should lead the decolonisation process?

Decolonisation was originally intended as a revolutionary concept and approach, but contemporary debates, including in the global North, have arguably mainstreamed the concept of decolonisation. Indeed, one might ask whether the debate on decolonising academia itself has been colonised. This does not make decolonising academia irrelevant. On the contrary, it emphasises the importance of continuous attention to how structural imbalances of inequality are reproduced.

If poorly concieved current debates on "remote fieldwork" can lead to data extraction mechanisms than reinforce inequalities and racial hierachies

African scholars have frequently pointed to inequalities in research relationships with Northern scholars. Yet there have, until recently, not been many successful attempts in African academia to establish united visions and collaborative initiatives that address these inequalities, despite long-standing debate and advocacy on principles of non-alignment and Pan-Africanism. As one Kenyan workshop participant put it:

“Why do we still depend on the North to drive agendas that we need to drive? In the last two months we have run seminars on decolonising knowledge. [However,] if we look at how partnerships are built, there are a lot of researchers [in Africa] that work closer with Northern than African researchers.”

African networks certainly do exist, but it is important to further strengthen collaborative efforts in African academia that can establish tangible joint activities to strengthen African-led research.

What to do?

The authors of this brief believe in and support international collaboration in development research. However, there is a need to focus the overall aim of development research funding more strongly on breaking down inequalities between South and North – and indeed, on eradicating the South-North dichotomy altogether. Basic first steps include:

- Institutions in Africa and the Global South should lead efforts to address structural inequalities in research. Funders in the North can support this endeavour, e.g., by financing South-driven regional and international networks that work on issues such as enhancing access and equality in publishing, and recognition of Southern researchers and fieldworkers.

- Support efforts to strengthen the production and global dissemination of knowledge by the South. This can include ensuring funding for South researchers to present work internationally and rewarding funding proposals where partners commit to publishing some articles in regional Southern journals (thus providing an incentive to overcome resistance to this).

- Open up research funding towards a more contemporary scope whereby development challenges are researched as global issues instead of issues specific to the South. This includes providing the means for collaborative South-North research across regions and levels of scale and allowing Southern researchers to conduct research in and on the North. This will help overcome the “glass ceilings” that constrain South-based academics’ engagement in international research discourse.

- There is a need to establish national spaces for discussing decolonisation. This could include PhD summer schools and curriculum development, to ensure that the issue is on the agenda for younger researchers and support them as they face dilemmas when engaging with inequalities in research.

- Abandon the emphasis on “capacity strengthening” of African universities as a key qualifying criterion in calls for research proposals. This frames the relationship as unequal from the outset, whereas in practice it is usually more a process of mutual learning. This does not mean that doctoral-level education and similar activities are unimportant, but PhDs are a standard academic endeavour and do not need to be wrapped in capacity enhancement terminology.

- Reconfigure communication between funders and research partners. North-based research institutions tend to sit at the nexus of this communication to the detriment of insights and perspectives from their Southern partners. Even if a research project is led by a partner in the North, funders should be more active in seeking and encouraging direct feedback from Southern partners (beyond rare evaluation missions).

Authors: Abdirahman Edle (University of Nairobi and University of Copenhagen); Alphonce Mollo (University of Nairobi and University of Copenhagen); Eva Dzegblor (University of Ghana); Fatima Dahiir (University of Nairobi and University of Copenhagen); Iben Nathan (University of Copenhagen); Jackson Wachira Waiganjo (University of Nairobi and University of Copenhagen); Joanes Atela (Africa Research and Impact Network); Karuti Kanyinga (University of Nairobi); Kwesi Aning (Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre); Martin Marani (University of Nairobi); Mikkel Funder (DIIS); Mustapha Abdallah (University of Ghana); Nauja Kleist (DIIS); Paul Stacey (Roskilde University); Peter Albrecht (DIIS); Peter Bembir (University of Ghana); Rahma Hassan (University of Nairobi and University of Copenhagen); Sylvia Rotich (University of Nairobi and University of Copenhagen)

DIIS Experts