Fragile states

- Denmark should seek to create a space in international policymaking where a collective vocabulary can be created that is based on mutuality and collaboration rather than hierarchy and judgement. The UN is a good place to start.

- Denmark should actively work to disentangle development issues from security risks, and to prioritise development for the sake of development rather than for narrow national security concerns.

- Context-specificity – rather than universally applied policy concepts – is the basis of greater understanding of the world and stronger interaction both with and within it.

Over the past decade the fragile state concept has lost its academic mojo, cast over the years as analytically vacuous, overgeneralised, and a normative judgement on countries in the global South, commonly sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. But despite these critiques, its use in policy circles has continued unabated. We contend that this is precisely because of its vagueness, which allows donors to use it to justify a wide range of interventions in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Mali and Somalia.

The seemingly coherent narrative that characterises fragile states as those suffering from instability and conflict underpins the notion that international interventions are necessary to mitigate the risk they pose to ordinary people and global security. However, interventions primarily reflect the interests of those who intervene, and the notion of fragility is a part of Western countries’ rationalisation for doing so.

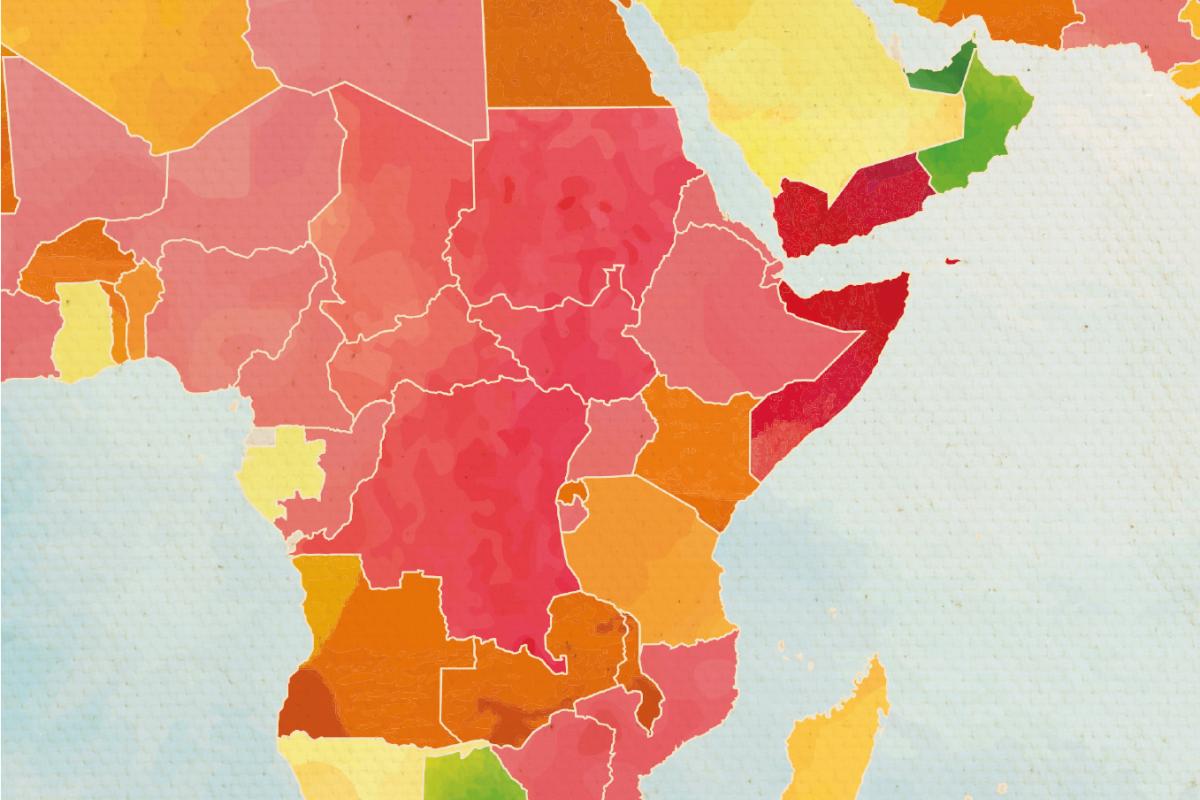

Instead of narrowing the scope of state fragility, policymakers have tried to counter resistance to the concept by doing the opposite and expanding its meaning to become ever-more encompassing. This is reflected in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) designation of no less than 57 countries and territories as ‘fragile’ or ‘extremely fragile’.

Fragility evolved out of debates on the failed state that emerged in the early 1990s, at that time reserved for a few cases such as Somalia and Sierra Leone that imploded into war and bureaucratic collapse in 1991 and 1992 respectively. The concept has since been detached from the state, and fragility is now seen instead as a spectrum of situations which, in principle, have the potential to affect all areas of life, including at an individual level. It is our argument that such an expansive notion of fragility, attached to situations rather than states, becomes an all-encompassing concern, which opens the door to more and more intrusive interventions.

Ultimately, because the use of the fragile state concept is a judgement by the West of countries in the global South, it is political. And because it is political, it is also deeply contested. However, a broadly used definition is the following taken from the OECD:

‘The OECD characterises fragility as the combination of exposure to risk and insufficient coping capacity of the state, systems and/or communities to manage, absorb or mitigate those risks. Fragility can lead to negative outcomes including violence, poverty, inequality, displacement, and environmental and political degradation’.

OECD. States of Fragility 2020.

From failed states…

When ‘failed state’ entered the academic vocabulary in the early 1990s, the concept was construed to capture a world transformed by the end of the Cold War. It was seen as an unprecedented phenomenon of states that were considered incapable of upholding themselves as functioning members of the international community.

Analysts in the West even likened the failure of states to mental and physical illness thereby legitimising the establishment of trusteeships and guardianships where governments had stopped functioning, as witnessed in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo and East Timor during the 1990s. The failed state rhetoric confirmed a global hierarchy of states where some, the West, could pass judgement on the rest and especially those located in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, i.e. many former colonial territories of Europe. At the same time, failed states transitioned from being a development concern to being a key security threat to the US and its Western partners.

The failed state, as disturbing as it might have been when it emerged in the early 1990s, was an anomaly. It was extremely rare that governments collapsed or were removed and not immediately replaced as happened in Somalia after 1991 (where a government did not return to Mogadishu until 2012).

...to fragile states...

In the 2000s failed state was gradually superseded by ‘fragile state’ as the dominant analytical category, which indicated a small but important shift in meaning. Fragile states were described as not quite failed political entities, but still dysfunctional and characterised by central governments and bureaucracies that were unable to provide basic public services to populations within their jurisdiction. This broadened the scope of the concept considerably in terms of the number of potential fragile states and therefore also types and sites of interventions. Rather than being an outlier in policy, intervention became mainstream.

The seemingly coherent narrative of fragile states as those suffering from instability and conflict underpins the notion that international interventions are necessary to mitigate the risk they pose

‘Fragile state’ became the catch-all category for a wide range of developmental weaknesses, and indicators of fragility were both selected and analytically applied by states in the West. These processes were ultimately set in motion to rationalise and legitimise whether and when to intervene. At the same time conflict became an increasingly integral part of how the concept was applied, because states were seen as either particularly vulnerable to transnational causes of instability – terrorism, migration, climate change – or exacerbating already-existing insecurity and war.

…to fragile situations.

Since the early 2000s the notion of fragile states has been criticised for being overly state-centric, resulting in attempts to construct alternative frameworks of analysis. The OECD has played a key role in this process of establishing a more multidimensional understanding of fragility. An example of this is the emergence of ‘fragile situations’, which expands the notion of fragility from being a condition of state institutions to one that potentially affects all areas of life. Doing so paves the way for ever-more invasive and expansive interventions, where concepts such as ‘risk’ and ‘coping capacity’ introduce new layers of ambiguity and further discretionary power to the intervener.

Reconfiguring development

Labels are deeply relational and political. When they represent poorly defined – or overly flexible and simplified – concepts, they can be exploited in the interests of those who develop and apply them. Fragility is one such label. Its political usefulness reflects historically embedded structural inequalities between the global South and the West, and it continues to reinforce those inequalities. While this condition will be difficult to change, establishing a more level playing field is crucial, one where the point of departure is not a hierarchical relationship, but one of mutuality and collaboration.

The fragility agenda is symptomatic of a shift where development has gradually been subsumed into security concerns; our (Western) security concerns. In this process, the entity posing a risk has gradually become more localised (state à community à individual) while fragility has become more encompassing. We need to challenge how we hierarchise the world with our concepts and strive for greater context-sensitivity in recognition of our own limitations.

DIIS Experts