Timbuktu: A quest for visual engagement with jihad in Africa

When the stoning of an unmarried couple in the northern Mali town of Aguelhok wasfilmed and diffused on the Internet by jihadi terrorist in 2012, it hardly stirred international public opinion.To Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissako (Bamako, Waiting for Happiness), it proved that the suffering caused by jihad in West Africa does not get the same media coverage as in Syria/Iraq, Afghanistan and Europe.

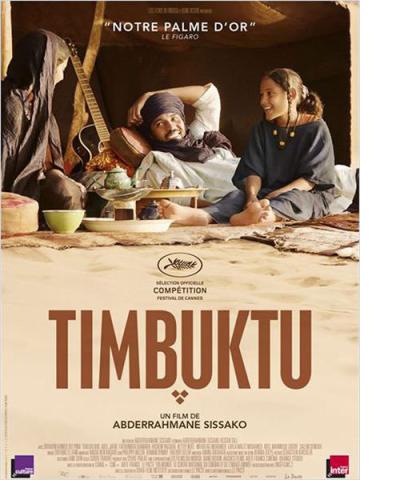

In his latest feature filmTimbuktu,Sissako therefore decided to portray the unseen drama of jihadi occupation of a desert town in northern Mali in 2012, a moment in time when the area was inaccessible to researchers, journalists and photographers.

Although the ‘occupation’ of the main towns in northern Mali by these jihadi fighters is officially now over, the lack of coordination and trust among security actors continues to result in many casualties among civilians, external actors (the UN peace and stabilisation mission in Mali, called MINUSMA) and humanitarian organisations (the Red Cross). The security situation in northern Mali has spiralled downwards since the 2012 events, which is why parts of the movie were shot in neighbouring Mauritania.

Taking home several prizes from festivals such as Cannes and FESPACO,Timbuktucommemorates the dramatic occupation of the West African city of Timbuktu (Mali) by a jihadi group called Ansar Eddine in 2012.The movie begins with jihadists practising their shooting skills on a row of wooden African statues, in their eyes the ultimate symbol of the problematic local African blend of Islam and so-called pagan or animist remnants. The destruction of these idols symbolises the ideal reformist goals of jihad: to purify Islam from syncretism and idolatry. Sound familiar?

The audience is led to sympathise with a proud nomad (cattle herder) and his family living in the desert dunes on the outskirts of Timbuktu. They are among the few who decide not to flee, and they try to survive in an area increasingly policed by ‘foreign’ jihadists, who cooperate with some of the locals. The poetic scenery and the beauty of the lifestyle of these nomads are painstakingly over-romanticised; and to underline the drama, the movie uses rather obvious metaphors. Fortunately, Sissako compensates somewhat for this by inserting humour, absurdity and understatement: a young rapper who fails to talk convincingly in front of the camera about why he gave up on his life as a musician to serve God; the jihadists who have to rely on locals who do not speak (or only very badly) their language (Arabic for the Algerians, English for the Nigerians); technology that does not function at crucial moments; and donkeys that come and go as they please. The double standards of the jihadists themselves are addressed with a good deal of irony: the sexual desires, football passion, smoking and dancing that they prohibit for the locals are just as much a part of their own daily lives. This irony also deconstructs the idea that this is a war of clashing religious ideologies. The characters are people of flesh and blood navigating the opportunities available to them in their respective situations.

While jihadists worldwide currently make it to the international media’s front pages, Sissako reminds a Western audience that jihadi violence in the African region victimises fellow Muslims more than anyone else. Shooting a movie for a broad audience to denounce the African drama of terrorism is however a complex balancing act on a very thin rope. By taking time for romantic aesthetics Sissako makes the audience identify with his victims, but this comes with the risk of reinforcing age-old clichés of African suffering. Nevertheless, Sissako does manage to underline a certain universality of human suffering and in so doing points to the strong geopolitical blind spot for mediatisation and commemoration of victims of jihad in Africa. The current insecurity caused by jihadists from Lybia to Nigeria suggests we might want to give human suffering in this so-called southern backyard of Europe more visibility. At the same time, it is precisely the visibility and media-savviness of jihadists that feed into their current success. Seen from that perspective, the relative silence around African jihad could paradoxically turn out to be an advantage. Therefore, making a realist feature movie like Timbuktu on the issue, is probably the most diplomatic in-between solution.