Three frontlines in Africa's resource conflicts

- The demand for natural resources is increasingly shifting from oil and gas to the precious minerals that are needed for greener technologies.

- The ‘green transition’ and nature conservation, although vital to curb climate change, are frequently carried out at the expense of local, often poor, communities’ livelihood.

- As windmills and solar panels are set up, Africa’s drylands are emerging as an area of increasingly militarised conflict over access or usage.

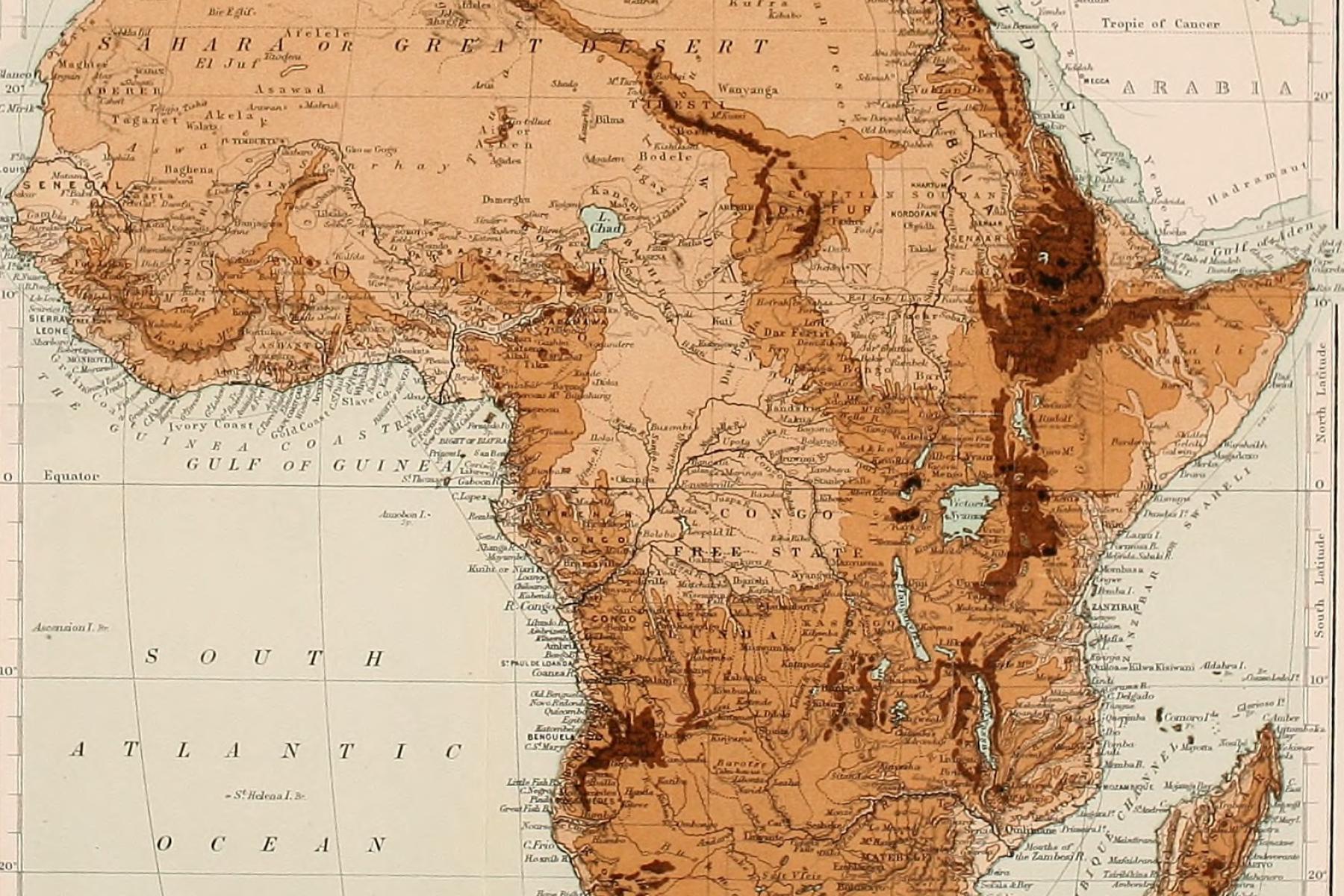

Conflicts over land and resources are nothing new on the African continent. However, as global attention has turned towards environmental issues – as well as Africa’s rich renewable energy sources and precious minerals – the nature of these conflicts has changed. Research shows three frontlines that investors, humanitarian actors, and policymakers need to be aware of as they invest or engage in green initiatives in Africa.

First, global investments in renewable energy sources such as solar panels, windmills and geothermal energy, along with the tech industry’s demands for precious minerals, are resulting in casualties and conflicts just like those connected to the extraction of oil and gas. Second, the growing demand for nature conservation increases the potential for conflict over control of essential resources and land. And third, previously undesired areas such as drylands are gaining traction as sites for renewable energy initiatives like windfarms and are becoming new battlegrounds for control.

Green transitions

Oil and gas are no longer the main extractives when it comes to energy on the African continent. They now share that status with tech industry minerals such as aluminium, cobalt, copper, lithium and manganese – needed for smartphones and solar panels – as well as land appropriated for the installation of windmills, solar panels and geothermal installations. Although these ‘newer’ sources of energy are directly linked to the global green transition, their extraction and associated land appropriation lead to conflicts that are comparable to those surrounding oil and gas.

Getting to grips with these dynamics of exclusion and suppression in the name of curbing climate change means understanding the broader implications of the green transition for local communities.

Because the extraction of oil and gas is linked directly to the global climate emergency, it has been relatively simple to point to the ills of the industry, for instance, when it leads to the loss of habitable land for local communities. This is less straightforward in the case of the green transition, as its goals are more easily justifiable in current debates on climate change. Yet, extraction and land appropriation related to the green transition demand similar casualties, for instance, when people are forcibly displaced to make space for windmills. Getting to grips with these dynamics of exclusion and suppression in the name of curbing climate change means understanding the broader implications of the green transition for local communities – as well as the moral question of whether this is an acceptable consequence of the green transition locally and globally.

Nature conservation

There is growing pressure on allocating protected area status to land and water bodies in Africa. With 15% of land and sea under protected status globally today, it was agreed during the 2022 UN biodiversity conference, COP15, that targets should be doubled to 30% by 2030 (known as 30 by 30). Most areas deemed suitable for conservation contain populations that use the lands they inhabit in various ways and face displacement when conservation practices are expanded. The push to increase conservation areas has already heightened the potential for conflict over who can control or be excluded from using essential resources.

Land appropriation generates accentuated patterns of exploitation in the name of conservation, leading to resistance from local communities to what is perceived as forceful impositions by state agents, private security companies, and other groups spearheading conservation. Although resistance by those affected by conservation practices is not new, the way dynamics around them play out are changing. Protection of wildlife and nature has entered global policy agendas much more acutely, leading to more fragmented funding streams that include private as well as public sources (examples among many others include Jeff Bezos’s Earth Fund and principles of inclusionary approaches such as the International Union for Conversation of Nature’s ‘Nature-based Solutions’).

The last decade has also seen a fragmentation of approaches used for conservation, including elements of conflict resolution (e.g. peace parks initiatives), militarised responses (e.g. anti-poaching units) and initiatives that are inclusive and community-based on paper but exclusionary in practice (e.g. fencing of former pastoralist grazing areas). While accentuated power dynamics and accelerated plans for upscaling nature protection have become a global policy priority, there is a flipside to this movement: an undeniable increase in conflict potential, which is already visible in many localities across the continent.

When international corporations appropriate land in drylands to set up wind farms or militarise exclusionary nature conservation initiatives, some people are bound to be marginalised.

The drylands

Few, if any, pieces of land in Africa are outside formal ownership or control by organised user groups. The best agricultural lands are long claimed following decades of land reforms, (re)settlement schemes and informal land appropriations. While the lawful status of ownership may not in itself alleviate contestation, struggles have for the past decade moved into areas that previously were seen as inhospitable and undesirable, for instance in northern Kenya. These areas are now being increasingly sought after and fought over, whether by pastoralists, farmers of different wealth classes, private investors, or to make public infrastructural investments.

The demand-driven movement into peripheral drylands to appropriate natural resources, and the contestations that follow, redefine what is considered scarce. Resources that were previously seen as ‘not worth the struggle’ are now being pursued, which heightens the potential for conflict in spaces that hitherto were relatively peaceful.

For this reason, drylands can be conceptualised as a new frontier or even as the new epicentre of conflict over natural resources.

Global policy regimes that shape local conflicts

Scarcity has driven and is driven by global policies, and push conflicts over the various types of resources, armed and political, into new spaces. When international corporations appropriate land in drylands to set up wind farms or militarise exclusionary nature conservation initiatives, some people are bound to be marginalised. In turn, this generates responses and protests, which again may harden the methods used to maintain the appropriations.

Global policy agendas relating to green energy and nature conservation are pushing the fight over resources into new frontiers. These developments can indicate a newfound sense of resource scarcity that intertwines with the pressure on existing resources from climate change and population growth. Adding to this, the implications of climate change – that is, more unpredictable and extreme weather events, less rainfall and increasing temperatures – accentuate pressures on livelihoods as productive land becomes scarcer.

At times, the global narrative of climate change as an impending doom can be so influential, that it heightens the stakes of contestation and the risk of violent conflict. Indeed, it can lead to the recruitment into violent organisations, particularly of young men in the pursuit of alternative livelihoods.

With these dynamics come the potential for greater instability, and more militarised responses to gain access to or defend formal or informal rights of usage – by the state, private security companies, and other groupings that may or may not be affiliated with a central government. In this way, the relationship between natural resources and conflict in Africa is changing form, from its places of occurrence, what it fosters, nurtures and generates, to who is responding to it and how.

The brief is an output of the conference “Natural Resource Management and Conflict in Africa” held in Copenhagen on 26-28 June 2023, a collaboration between the Danish Institute for International Studies and the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana. The conference was funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs with support from the Danida Fellowship Centre.

DIIS Experts