Managing Africa's resources equitably demands accountable states

- When in Africa, foreign investors should live up to the same legal standards as in their home state.

- African leaders and governments should be consistent about only trading with strong, inclusive and accountable institutions.

- Policymakers and politicians in Africa and beyond should be asking: What are the benefits for the locals?

- Any interventions need to be considered for their political role and what kinds of existing power structures they end up supporting.

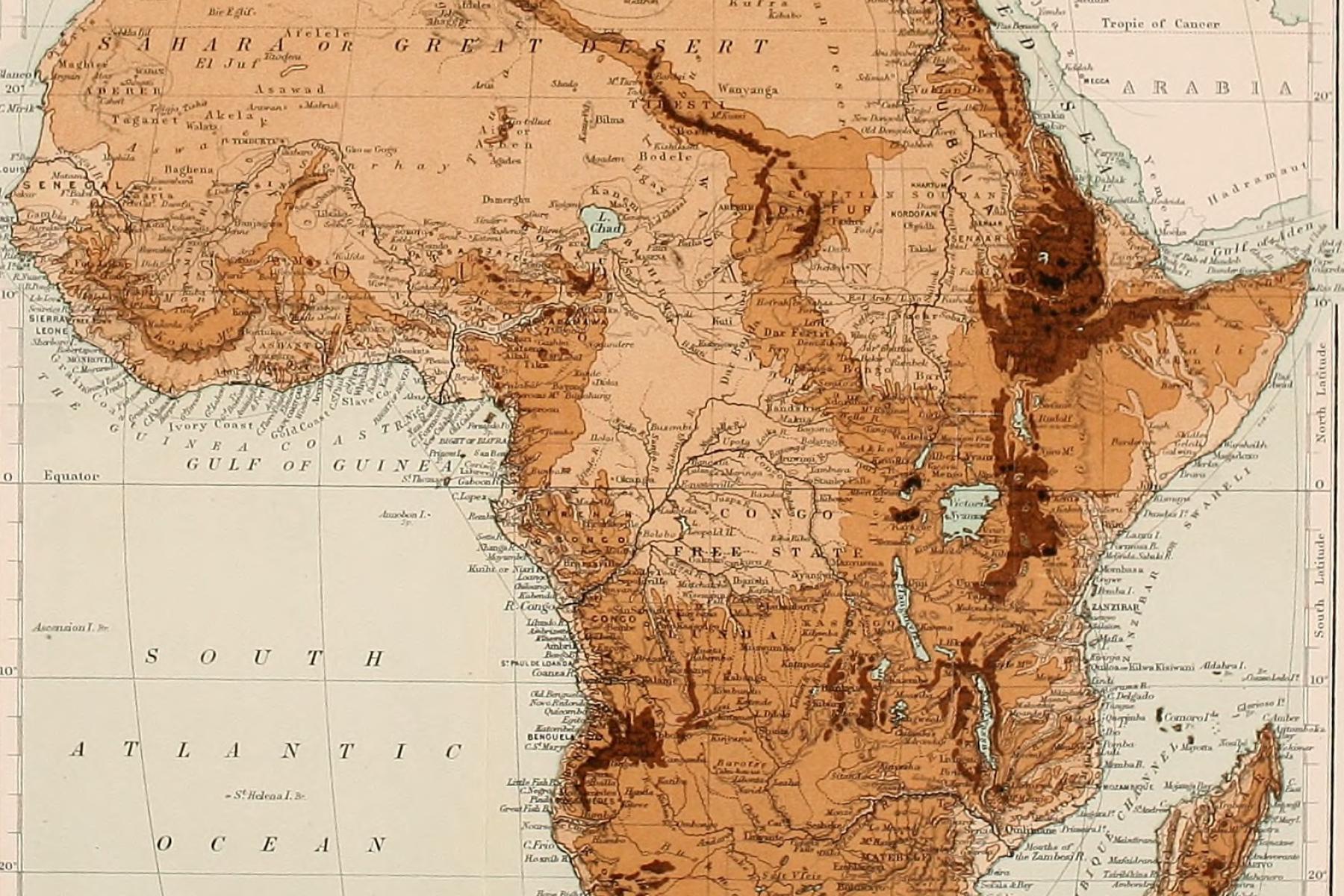

Africa’s vast natural resources present both opportunities and challenges. Securing their sustainable extraction depends on African states’ ability and willingness to enforce equitable legislation and policies. This does not take away the huge — and historical — responsibility of external actors from Asia, Europe and North America.

In 2019, Ghana banned rosewood extraction following years of over-logging that had decimated these slow-growing trees. Nevertheless, illegal harvesting and export of rosewood have continued since the ban. Research shows that the Ghanaian state has been unable or unwilling to deal with the violations because some of its representatives profit from these illegal activities.

The situation with rosewood in Ghana is not an isolated incident. Across the African continent, states and governments are passing policies in relation to the management and use of natural resources within their territories. Yet criminal networks, both local and international, often challenge, frustrate and manipulate these policies, in some cases working alongside state institutions and their representatives. In East Africa, recent studies present similar patterns with respect to sandalwood, where well-organized and resilient transnational criminal syndicates engage in the extraction and smuggling of this endangered tree species.

Securing inclusive and sustainable exploitation of Africa’s natural resources begins and ends with state legitimacy. The responsibility for resource management ultimately lies with those who have the mandate to enforce policies, that is, African politicians and policymakers. Even the clearest legal frameworks become ineffective and meaningless if politicians and officials disregard them.

At the same time, these national and local dynamics are in many ways entwined with international relationships, as Europe and Asia have sought to capitalize on Africa’s rich resources. Europe, despite having officially withdrawn from Africa, still exerts influence and, in many cases, benefits disproportionately from the continent’s wealth. Given this ongoing history of exploitation, it is imperative for African governments not only to manage their resources for the benefit of their populations, but also to hold external state and private sector actors accountable for the way they do business.

The heart of the matter: inequality and exclusion

The concept of ‘elite capture of the state’ denotes a form of neo-patrimonial practice where business-people and politicians collaborate to further their own interests through the manipulation of state institutions. This typically means neutralizing enforcers of the law, or bypassing legislation completely. For decades, scholars have debated whether donor-driven development programs should work in tandem with or counteract these socio-historical dynamics. For now at least, such dynamics are among the primary factors in diminishing the state’s capacity to consistently deliver services and ensure security for their citizenry. Owing to this fundamental circumstance, investments in green sectors like geothermal energy and wind power, as well as tourism-driven growth in the conservation sector, have often been non-inclusive. Indeed, in some instances, legal protocols have been skirted to seize land for these projects, not only to move the green transition forward — a laudable objective — but also to make a profit.

Even the clearest legal frameworks become ineffective and meaningless if politicians and officials disregard them.

A well-known case is the Lake Turkana Wind Power Project in northern Kenya that can provide green energy for one million households. Although this is a positive scheme in environmental terms, the Kenyan court ruled that the local community’s land was unjustly expropriated for the project. However, this verdict did not result in returning the land to its original owners. Instead, the responsible politicians were requested to make the land transfer legal.

The Lake Turkana Wind Power Project, alongside similar initiatives, highlights a central challenge in addressing Africa’s resource conflicts. Drylands — like Turkana — have become a frontier for green energy, and traditional users that already reside in these spaces are generally being ignored. There is a need for a state — an overarching body with geographical reach — that oversees and manages resource extraction. However, this state must be representative of and accountable to its electorate, all while balancing external economic and political interests. Otherwise, it exacerbates inequalities, fuels local discontent, and undermines the very legitimacy and trust that the state is meant to uphold among its populace.

Communities living in and accessing Africa’s resource-rich areas often witness the degradation of their pastures and forests and are at the same time sidelined from the wealth that resources on or in the ground yield. As a result, many local actors, in their pursuit of access to and control over the land they live on, resort to illegal activities like small-scale mining or logging. This, in turn, has prompted a more militarized response from both state institutions and private companies, escalating tensions and leading to increasingly violent confrontations.

Mechanisms of exclusion and bypassing often lead to localized competition, conflict and resistance against the state which governments might label as illegal or even terrorist activity, partly to secure international support from the West as well as Asia. We have seen this in the Niger Delta’s oilfields, Ghana’s gold-rich regions, and more recently in Mozambique’s mineral-rich Cabo Delgado. In many cases, however, people are simply trying to make a living.

The need for a transnational perspective and the post-colonial critique

In the context of Africa’s natural resources management, the role of the state is pivotal. Yet, to truly grasp the complexities at play, one must also adopt a strong transnational perspective. This broader view helps illuminate the global implications of local and national resource conflicts within the continent. Chinese investors, commercial and trading interests are widely blamed for being exploitative, but products from China often end up being sold in European and North American markets. Understanding the movement of natural resources within and beyond the African continent and individual states is therefore crucial as we do not advocate for an overly state-centric perspective. It is necessary to maintain a focus on how to deal with unfair trade regimes and tax evasion by international corporations, which directly and indirectly shape states and drive tensions and conflicts over resources at both local and national levels.

At the same time, these national and local dynamics are in many ways entwined with international relationships, as Europe and Asia have sought to capitalize on Africa’s rich resources.

African politicians often see Western investment and engagement, for instance through ‘development cooperation’, as exploitative and neo-imperialist. For a Tanzanian fisherman or a Mozambican farmer, the demands for good governance from European and American donor agencies are distant and not immediately beneficial. However, they will understand and appreciate infrastructure projects, such as building a hospital or a road, which is what China does in return for accessing the continent’s resources.

Coupled with lingering resentment towards Europe due to its colonial history in Africa, the visible benefits from Chinese involvement garner a stronger endorsement of China among Africa’s populations, and by extension its resource extraction efforts. While it’s crucial to decode the global political and economic systems African resources are embroiled in, the primary responsibility to uphold the interests of local populations and address their needs still rests with the African state. In the end — history shows — there is no alternative.

The brief is an output of the conference “Natural Resource Management and Conflict in Africa” held in Copenhagen on 26-28 June 2023, a collaboration between the Danish Institute for International Studies and the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana. The conference was funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs with support from the Danida Fellowship Centre.

Authors: Peter Albrecht (paa@diis.dk ), Marie Ladekjær Gravesen (malg@diis.dk), Frank Agyei (Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology), Kwesi Aning (Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre), Richard Asante (University of Ghana), Deborah Atobrah (University of Ghana), Anne Bartlett (United Arab Emirates University), Sandra Bhatasara (University of Zimbabwe), Veronika Čáslavová (Masaryk University), Mamadou Cisse (Donkosira), James Drew (University of Gothenburg), Esther Egele-Godswill (University of Edinburgh), Sophie Erfurth (University of Oxford), Abel Gwaindepi (Danish Institute for International Studies), Rahma Hassan (University of Nairobi), Stig Eduard Breitenstein Jensen (University of Copenhagen), Saymore Ngonidzashe Sayid’Ali Kativu (Zarawi Trust), Eric Kioko (Kenyatta University), Kandie Kipkemboi (University of Eldoret), Per Knutsson (University of Gothenburg), Marie Müller-Koné (Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies), Alexandra Krendelsberger (Wageningen University & Research), Jeremy Lind (Institute of Development Studies, UK), José Jaime Macuane (University of Eduardo Mondlane), Kennedy Mkutu (United States International University, Kenya), George Tonderai Mudimu (University of Western Cape), Peter Narh (University of Ghana), Ndubuisi Nwokolo (Nextier), Robert Ojambo (Kyambogo University), Willis Okumu (Institute for Security Studies, South Africa), Nelson Oppong (University of Edinburgh), Evelyne Owino (Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies), Narcisse Mideso Vincent de Paul (Université Libre de Bruxelles), Lindsey Pruett (Cornell University), Paul Stacey (Roskilde University), Ilse Renkens (Danish Institute for International Studies), Padil Salimo (University of Eduardo Mondlane), Janpeter Schilling (University of Kaiserslautern-Landau), Pius Siakwah (University of Ghana), Mkuti Sky (Independent Institute of Education, South Africa), Ophelia Soliku (University of Business and Integrated Development Studies, Ghana), Mike Speirs (Danish Institute for International Studies), Dzodzi Tsikata (SOAS University of London), Mads Yding (University of Oxford).

DIIS Experts