Renewable energy in Africa is about more than climate change

Development assistance for new renewable energy in Sub-Saharan Africa is increasingly being used to mobilise additional private capital. Recipient countries do not always share the priorities of donors. Realism and long-term support are key.

■ Continue funding, but also acknowledge different interests and objectives, in order to move new renewable energy to scale.

■ Balance the support for market development with support to government entities.

■ Support longer-term capacity-building to ensure energy sector sustainability in recipient countries.

■ Adopt flexible approaches and ensure independent advice to governments and institutions.

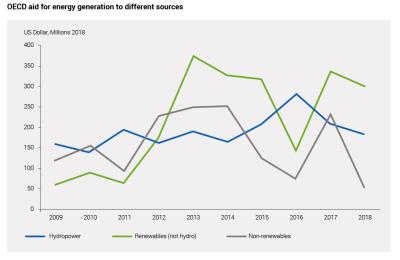

Investments in new renewable energy like solar and wind are increasing rapidly in sub-Saharan African countries, albeit from a low starting point. Development assistance plays a key role in this development as it increasingly is being used to mobilise private development finance. This change has occurred in tandem with the maturation of new renewable energy technologies, which has made them more price competitive. In the 1990s and into the 2000s, large hydropower projects were also implemented with donor support, but concerns over sustainability have made Western donors focus more on new renewable energy over the last couple of decades. China, in turn, has become a more significant actor in hydro projects as well as in coal and gas.

Previously, aid for new renewable energy tended to be aimed at developing or adapting specific types of technology to African contexts or at promoting specific projects. Now, it is increasingly being channelled into larger programmes and integrated into energy system planning.

At the same time aid is increasingly being used to promote an enabling environment and to mobilise private investments and finance. Whereas such market-led solutions have contributed to cheaper renewable energy projects they also tend to be very complex and may pose financial and managerial risks to recipient countries with limited capacity. Recent stories of the oversupply of energy from private producers in Kenya, Rwanda and Ghana document this. Contracts may pose a threat to state power utilities and state coffers and suggest that governance and administrative capacity in recipient countries is crucial.

Bilateral donors often promote and finance projects and programmes in areas where their own companies have strongholds.

Market-led approaches

Among the notable recent market mechanisms being promoted by development assistance are feed-in tariffs (FiT), renewable energy auctions, and mini-grids, which all typically involve the participation of private sector actors. FiTs involve a fixed price for energy, initially a de facto subsidy to energy producers at a time when the cost of new renewable energy was higher than conventional sources of energy.

Renewable energy auctions are of a more recent date and they are more focused on bringing down costs. They are used for bids from independent power producers (IPPs) for long-term contracts with a government-owned energy utility. Mini-grids are decentralised power networks and they have become more prominent in rural electrification. They too are characterised by an increased focus on crowding in private finance.

These new mechanisms may attract global lead firms and international finance, but contracts and financing models are complex, and their risks and implications are hard to assess for low and lower-middle income countries with less developed capital markets and limited public and private sector capacity. At times, donor organisations play so significant roles during implementation that the ownership of programmes is unclear to outsiders. In Zambia, the involvement of donors in auction and FiT programmes reportedly led bidders to perceive them as donor tenders, not government ones. Research into the outcomes of these particular combinations of development assistance, market-promotion and new renewable energy is still limited.

Do not undermine capacity-building in the quest for cheap energy

Whereas aid has helped promote new renewable energy at still lower prices there is a tension between reducing the cost of new renewable energy through market-led approaches on the one hand and the sustainability of these approaches in African countries with limited capacity on the other. The stories of oversupply point to this. Moreover, support is often linked to specific projects and interventions, there being less focus on capacity at the system or sector level, although this is clearly needed as well.

The frequency with which energy projects and programmes have been initiated as a response to energy crises also points to problems with long term planning capacity.

Past experience suggests that medium- to long-term approaches and more comprehensive efforts to build capacity are important. In the years of fast- tracked liberalizing reforms promoted by donors, implementation often stalled due to different priorities of governments or lack of local capacity. This to some extent changed as donors became more flexible and governments and donors developed a joint agenda of improving access to modern electricity and more efforts were made to build the capacity of existing state utilities and institutions. There is a risk that these lessons are forgotten in the quest for cheap new renewable energy

Many African countries have signed up to the Paris agreement on climate change, but energy projects on the continent often display other priorities than sustainability and decarbonization.

Relations between donors and recipient countries are however not always conducive for facilitating such processes. The continued pursuance of large-scale hydropower and fossil-fuel projects by many African countries suggests that they may be interested in new renewable energy more due to the availability of donor funding than out of interest in sustainability, decarbonization and market-driven new renewable energy. Many African countries have signed up to the Paris agreement on climate change, but energy projects on the continent often display other priorities than sustainability and decarbonization.

-

Kenya has mobilised donor funding and private capital for energy more effectively than most other countries.

-

Renewable energy accounts for 87% of Kenya’s electricity for the grid.

-

Hydropower and geothermal are the largest sources of energy but the country also has large wind and solar projects.

-

Like other Sub-Saharan African countries, Kenya came under pressure from donors to liberalise its power sector in the 1990s, but the link to the reform agenda is ambiguous.

-

Though donors pushed for renewable energy, three quarters of Kenya’s commissioned private power producers’ projects run on fossil fuels.

-

The choice to develop geothermal energy, with significant donor funding and dominated by a state utility, was as much about energy security as about decarbonization. Geothermal was seen as a domestic resource that could reduce the country’s importation of expensive fossil fuel products.

-

Coal still features in energy sector planning.

Improving access to cheap modern energy services tends to be their bigger priority. Similar questions can be asked about the interests and motives of the donors. Bilateral donors often promote and finance projects and programmes in areas where their own companies have strongholds. Multilateral banks play a prominent role in many reform and procurement processes, but as banks they also have a business case that may not always be easy to reconcile with being a main advisor.

Moving new renewable energy to a larger scale in sub-Saharan Africa requires acknowledgement of these different interests and objectives and being realistic about how to bridge them. More funding is needed if a transition to cleaner energy and universal access to energy services in recipient countries are to be achieved. This should include not only continued support for new renewable energy. It should also support longer term energy sector development, including capacity- building and more independent advice.

This DIIS Policy Brief has received financial support from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. It reflects the views of the authors alone.

DIIS Experts