Private investments in climate and sustainable development are still not catching on in Africa

- The African continent is considered the next frontier of private sustainable finance, but its GSSS market accounts for less than 1% of the global market value.

- The market remains uneven, with South Africa dominating most GSSS bond issuances through commercial corporates (mainly banks).

- Deals have remained erratic and hardly surpass the benchmark size of USD 500 million, which is necessary for impactful projects.

- Of the GSSS bonds, the green bonds seem to overshadow other equally important social and sustainability-focused bonds.

In the world of sustainable development and climate action, considerable hope is placed on private-sector financing. The main private finance instruments are the green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds. The proceeds of these bonds are intended for use in achieving social, environmental and climate objectives. These bonds have mandatory progress reporting, which appeals to sustainability- focused investors. However, research shows that, despite GSSS bonds’ high potential for green and sustainable projects, compared to other private financing mechanisms, this potential is yet to be realised in Africa.

Green-labelled bonds are popular

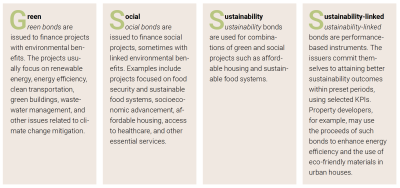

GSSS bonds are fixed-income financing instruments for projects that benefit the environment, climate and sustainable development. Green, social and sustainability bonds (the ‘GSS’ in ‘GSSS bonds’) are the useof- proceeds instruments; hence, the funds raised by issuing these types of bonds must be used to finance green, social and sustainability projects. Sustainability- linked bonds (the last S in ‘GSSS bonds’), on the other hand, are performance-based instruments using selected key performance indicators (KPIs).

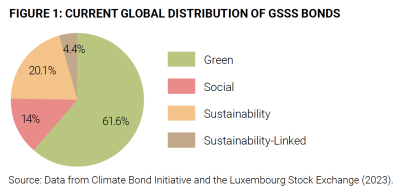

Figure 1 illustrates the global GSSS bond distribution. Green bonds lead at 61.6%, sustainability bonds at 20.1%, and social bonds at 14%. Sustainability-linked bonds are the smallest at 4.4%. Green bonds, especially those for clean energy, are profitable and are prioritised, but in general, green bonds are favoured as they offer a straightforward means for firms and organisations to convey sustainability since ‘green’ has become an essential tag. Sometimes, green claims are dishonest, as debates on greenwashing have shown.

Africa’s GSSS market share is low

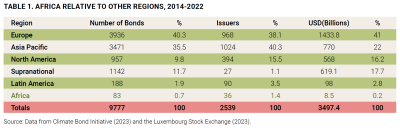

Table 1 illustrates the minuscule size of the African GSSS markets relative to other regions. Europe has maintained dominance across all classes of GSSS bonds over the years and has led in terms of cumulative value and volumes of GSSS bonds issued since 2014. In contrast, African issuances have remained very low in value (0.2%), number of bonds issued (0.7%), and number of issuers (1.4%). The combined value of African GSSS bonds is below USD 10 billion, spread across all GSSS categories and all issuing countries.

Uneven distribution and small deal sizes

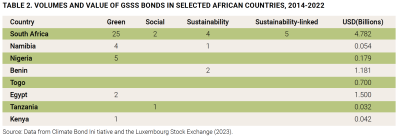

GSSS issuances are unevenly distributed in African countries. South Africa dominates over 60% of the GSSS market, with many African countries yet to participate (Table 2). Mobilising private finance through GSSS bonds is intertwined with other impediments to economic development in low-income nations. Each country’s ability to participate in the GSSS markets is influenced by its GDP per capita, financial market depth and investment climate. In this sense, development and climate finance is linked to general financial stability.

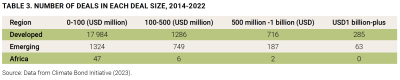

The second issue is the small size of the few deals finalised in Africa. Table 3 highlights that deals are rare and small. No deal has exceeded USD 1 billion. Deal size is crucial because many sustainable projects require substantial capital. This also implies that investors are careful about big projects in less stable economies, with the tendency that investors prioritise GSSS bonds from regions with reputable issuers. In Africa, such issuers are rare, as most economies are dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises with a few large corporations. Collaboration is thus required for large-scale deals, which are vital for decarbonising the energy sector.

The green transition agenda remains an energy agenda

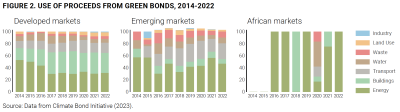

Figure 2 illustrates some of the principal uses of green bond proceeds in Africa alongside the patterns in developed and emerging markets. The underlying message is that the investments in the energy sector remain very low, but as a share of the totals, the energy sector attracts most of the green bond proceeds. The green transition agenda is largely an energy agenda. The energy sector is a major focus for green bonds, particularly in emerging markets and Africa, where in certain years (2016, 2017, 2019 and 2022), all proceeds have been directed towards this sector. Clean energy is prioritised given that the power sector can accelerate transitions in other sectors, including industry, transport and buildings. While Africa is regarded as a possible next renewable energy superpower, only 45% of Africans can access electricity.

Moving forward

The optimism surrounding GSSS bonds, especially as a tool for unlocking private sector finance, must be tempered when looking at the current GSSS markets in Africa. What the GSSS bonds have raised on the African continent remains a drop in the ocean. Currently, there is no feasible framework to guarantee the success of these instruments at the required scale. Although there is hope that GSSS bonds could be the quintessential private finance instrument, this should not overshadow alternative private and public methods for financing sustainable development.

There are contexts where GSSS bonds are most suited, especially in energy sectors where prospects for cash flows are better than in other projects such as health care, which may take time to realise profit. In such cases, other approaches, such as blended finance, can be more fitting to allow risk sharing. In the interim, traditional funding approaches such as bilateral and concessional finance remain vital in direct assistance and, crucially, in catalysing private sector finance.

What should African countries do?

- African countries should develop taxonomies and frameworks for GSSS market expansion, including local currency markets. They need to establish credible commitment standards and reduce investor exit risks.

- By fostering public-private partnerships, African countries could learn from the financial corporations that have so far led in the issuance of GSSS bonds.

- African leaders could also facilitate national-level collaboration for strengthening market integration and increasing possibilities of joint issuances of GSSS bonds, especially for the bigger deals necessary for truly impactful projects.

What should advanced economies, multilateral development banks and donors do?

- Mitigating investment risks through de-risking mechanisms and catalytic grants is necessary to unlock private-sector financing. The role of official development assistance in catalysing private finance remains critical.

- Climate projects have global implications and, therefore, have become global public goods. African governments and stakeholders cannot be solely responsible for developing bankable projects, particularly from a climate justice standpoint. All international actors, both public and private, must contribute to pre-feasibility capacity building and project preparation.

- Honouring commitments and pledges made through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, such as those outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement and subsequent Conferences of the Parties, fosters credibility and international confidence around proposals. This is necessary for gaining support and solidarity for future proposals and enabling practical planning.

DIIS Experts