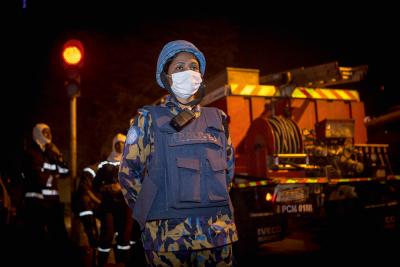

Peacekeeping in the shadow of Covid-19 era

UN leaders and member states should:

■ Sustain and where necessary boost funding for UN operations and other international actors to support host states’ efforts to manage the consequences of COVID-19.

■ Commit to maintaining current levels of UN deployments throughout 2020 and to ensuring that deployed personnel are not carrying COVID-19 in order to reduce uncertainty over the future of missions.

■ Offer specialists in public health management and related fields to strengthen planning within missions at UN headquarters and thus help manage the crisis.

COVID-19 has had an immediate impact on UN peace operations. Troop rotations have been frozen, and interactions with local populations minimized. Yet the long-term economic and political consequences for peacekeeping look more severe.

Just as Security Council members and the main contributors to the UN budget are facing a global recession, coronavirus or COVID-19 is liable to increase instability in fragile states, including those where the Blue Helmets are deployed. These converging challenges have the potential to reshape UN crisis management, but the results are uncertain. Tensions and conflicts aggravated by the pandemic could increase the demand for large-scale UN peace-keeping operations as bulwarks against instability and violence. But the financial pressures arising from the economic recession may push the UN to prioritize smaller-scale mechanisms as affordable alternatives,such as light-weight observer missions and civilian Special Political Missions. The UN Secretary-General,the Department of Peace Operations and UN member states need to work together to identify crisis-management tools that are both financially and politically feasible in the shadow of COVID-19.

Responding to the first wave of COVID-19

While nothing could prepare the UN for the enormity of the COVID-19 pandemic, peacekeeping officials have been able to draw on their experience with a number of other recent health crises as the virus has spread.

Peacekeeping forces were involved in managing ebola outbreaks in Liberia in 2014 and in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2019. Less positively, UN officials are still haunted by memories of a Nepali peacekeeping contingent that introduced cholera into Haiti in 2010. During the initial phase of COVID-19, the UN’s priorities – in addition to protecting its own personnel– have been to support public-health initiatives and ensure peacekeepers do not spread the disease.

Accordingly the UN immediately paused all troop rotations until the end of June and sent out guidance to ensure that those personnel who regularly deal with local populations did not spread the virus. UN police have been instructed to suspend training for local partners that involves “physical contact and proximity”and to avoid coming closer than two metres to civilians while on patrol. Many missions have also reduced military patrolling, and the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) put personnel into lockdown after a few tested positive for COVID-19 in March.

In Somalia, Al-Shabaab has accused African Union

peacekeepers (who are backed by the UN) of bringing

the virus into the country. Nonetheless, the UN has

succeeded in avoiding a ‘Haiti scenario’.

The overall number of infections in UN missions has been low, with 137 confirmed cases by the end of May, although the virus killed two peacekeepers in Mali. Some communities have continued to fear that international operations could be carriers of COVID-19. UNMISS has faced vehement attacks in the social media. In Somalia, Al-Shabaab has accused African Union peacekeepers backed by the UN of bringing the virus into the country. Nonetheless, so far the UN has succeeded in avoiding a “Haiti scenario”. In collaboration with the WHO, UN operations have taken steps, such as broadcasting health advice on UN radio and donating equipment to local medical centres, to help local authorities and communities manage the virus.

The coming crises

Although UN missions might have managed the immediate disruption of COVID-19 as best they can, the pandemic could have longer-term strategic implications for how the UN responds to violent conflict:

- Economic and political shocks arising from the pandemic threaten to undermine state institutions and complex peace agreements in the countries where the UN operates, reversing UN efforts to establish sustainable peace and creating the risk of new violence.

- Facing a global recession or depression, UN member states are likely to search for further savings in the UN peacekeeping budget (projected to be just over $6 billion in the next financial year), while also reducing financing for broader conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts.

- Squabbling between China and the US over the origins of the virus has increased frictions in the already tense Security Council and prevented a collective security response to COVID-19. While the permanent members of the council have generally continued to cooperate on existing peace operations, including routine extensions of mandates that are up for renewal, an overall decline in US-China relations could make it harder for the Council to agree on the terms for new operations or significant modifications to existing mandates.

To date, no UN peace operation has faced an acute political crisis attributable to COVID-19. Nonetheless, the pandemic is likely to foster further instability in many weak states. Food shortages and spikes in food prices stemming from COVID-19-related restrictions threaten to create unrest in many parts of the world this year. In the medium term, the intensifying global recession, coupled with aid cutbacks, is likely to leave many fragile governments facing budgetary crises, mass unemployment and elevated levels of public distrust and unrest.

In the near future, the Security Council is likely to

continue asking the UN to find cheaper options for

responding to crises.

UN operations will need to help manage these stresses in many of the countries where they are deployed by helping maintain public order and aiding governments and other actors in resolving disputes over how to handle COVID-19-induced political pressures. Peacekeeping forces and other international actors have an especially significant load to bear in cases such as the Central African Republic, where the authorities are already weak and under-resourced.

If COVID-19 does have a serious impact on one or more countries hosting a UN peace operation, the Blue Helmets may be expected to take on additional tasks, possibly including:

- Increased responsibility for facilitating and securing basic services, such as the delivery of food supplies and maintaining public order, that national political actors may struggle to deliver.

- Protecting and facilitating medical and public-health initiatives by the World Health Organization and NGOs, as UN peacekeepers have done in the DRC in response to ebola.

- Offering mediation support and political backing to help political rivals sustain peace processes and political bargains, despite social or political turbulence linked to COVID-19.

To undertake additional tasks, existing UN missions may need to maintain or increase their current resources and deployments. Growing instability and violence in countries where at present there is no UN force might also lead to calls to deploy a completely new UN mission. Will the UN be able to respond to such demands?

COVID-19 restrictions on peacekeeping

UN officials are expecting to face budget cuts due to COVID-19, as the pandemic will adversely impact member states’ resources. Many will want to focus their funding on global health, not peacekeeping.

The expected cuts may not come immediately. After the 2008 financial crisis, UN Member States did not kill off any Blue-Helmet operations overnight. Decisions to draw down and/or cut spending on existing missions came gradually in the years that followed, along with a general reluctance to mandate sizeable new operations. Although the operations in Mali and CAR were exceptions, even they were controversial with some Council members. In the COVID-19 era, the Council may take a similarly cautious approach, neither slashing costs nor risking much new expenditure on peace operations.

In the near future, the Security Council is likely to continue asking the UN to find cheaper options for responding to crises, such as special political missions, rather than large-scale Blue Helmet efforts. If COVID-19 leads to a new wave of crises in fragile states, the council’s collective instinct will be to look for ‘agile’ and ‘flexible’ low-cost responses, especially if tensions among the permanent members complicate debates over mandates. In this context:

- The Security Council will urge existing peace operations to handle COVID-related crises within existing resources, even if this means dropping other priorities.

- The Council is unlikely to mandate many new missions to handle COVID-related disorder.

- If the Council does launch new missions, they are likely to be relatively limited.

DIIS Experts