Joining hands in the Sahel

© EPA/Christophe Petit Tesson

Denmark should use its well-established position in the Sahel to bring European, North African and Sahel powers closer together when addressing the current challenges from jihadists and migrants in the Sahel.

with a role as a mediator between European,

North African and Sahel countries in combating

jihadism and curbing undocumented migration.

■ Danish mediation efforts should focus on aligning

the interests of regional powers like Algeria with

Europe’s foreign policy strategies.

■ Denmark should prioritize assisting the Sahel and

the North African countries in expanding their

economic and trade relations, e.g. through investments

in infrastructure that links the two regions.

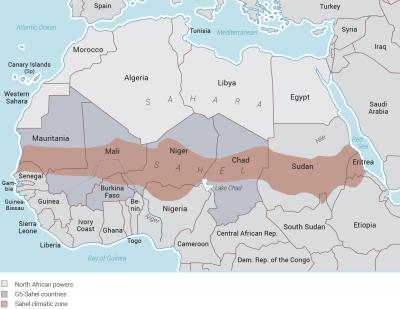

In the wake of the state’s collapse in Libya, European decision-makers have come to realize that state failure in the Sahel region, the semi-arid strip that runs for some five thousand kilometres across the African continent from Mauritania to Sudan, represents a challenge to European security and stability. The EU and its member states have identified undocumented migration out of the Sahel towards Europe and jihadist mass mobilization within the Sahel as the two immediate threats it wishes to confront in the coming years.

European foreign policy-makers have also understood that, in order to tackle these threats from the Sahel effectively, they must collaborate actively with the North African states – Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, once stability has been restored there. In this spirit, the foreign services of the EU and its individual member states have issued several strategic documents over the past decade identifying North African engagement in the Sahel as a key element in ensuring European stability and security. The core thinking in these strategic documents is that the North African states’ geographical position between the Sahel and Europe makes them geopolitically important. In addition, their comparatively larger resources mean that they are capable of assisting Europe in handling the crises in the Sahel.

European powers have most often engaged directly in the Sahel without proper inclusion of the North African states

However, the EU and its member states have provided few tangible results when it comes to convincing the North African powers to collaborate with each other and with Europe on handling the threats to the security, development and stability of the Sahel’s states and societies. Instead, European powers have most often engaged directly in the Sahel without properly involving the North African states. In particular, European countries have a poor track record when it comes to including Algeria, which, due to its role as Africa’s biggest purchaser of arms, and in the absence of competition following the collapse of Libya, ranks as the probably most important geopolitical North African power in the Sahel. A case in point was Operation Serval, the French-led military intervention against jihadists in Mali in early 2013. The Algerians initially opposed this intervention and agreed not to obstruct it only reluctantly. Another example is the so-called “G5-Sahel Initiative”, in which France, supported by other external actors, provides incentives for five Sahel states to increase their collaboration against jihadists and undocumented cross-border migration. Once again, Algeria has only reluctantly agreed not to obstruct this initiative as well.

In several recent cases where external powers have ignored the specific interests of regional powers, results have been poor – even when the world’s only global super power, the United States, was willing to massively deploy troops on the ground and assume full regional hegemony as in Iraq and Afghanistan.

It is still too early to evaluate whether these efforts to combat jihadists and control migration by working directly with the Sahel states and omitting or ignoring the interests of Algeria and possibly other North African states will succeed, though comparative analysis suggests it will not. In several recent cases where external powers have ignored the specific interests of regional powers, the results have been poor, even when the world’s only global superpower, the United States, was willing to deploy troops massively on the ground and assume full hegemony over the region as it did in Iraq and Afghanistan. In these cases, regional powers like Iran and Pakistan have extended their long-term influence: while the US grew weary of fighting and wished to retrench, the respective regional powers had little choice but to hang on in and keep fighting.

European foreign policy-makers should draw the lesson from these examples that, while integrating a regional power like Algeria into European foreign policy in the Sahel may seem complicated in the short run, it is likely to become significant in the long run.

It is not advisable for the EU and its member states to roll back their current direct engagement in the Sahel region, nor is it likely. However, European foreign policy-makers should address the failure to include the North African powers in their solutions to the Sahel crises more seriously. They should also recognize the limited strategic reach of their current efforts. In spite of the difficulties of bringing the unwilling and suspicious North African states onboard, Europe has a clear strategic interest in pursuing this goal.

First of all, such an engagement would entail a targeted diplomatic effort, including international dialogue between Algeria and Morocco to limit potential spoiling effects spilling over from their regional competition for hegemony into the security and stability efforts in the Sahel. Secondly, it would entail an active attempt to ensure equal support from major European powers such as France, Italy and Germany, each of which has their own core concerns to cater to. Finally, it would require ensuring proper support for the shared strategies of the Sahel countries themselves. While their high degree of dependence on external donor funding may limit their ability to counter policies elaborated by European and North African powers, their relative fragility and weakness have often prevented them from properly curtailing jihadism and migration. Ensuring proper bid-in by the local Sahel states is therefore of the utmost importance.

Denmark should aim to take the lead in the crucial effort to align the security and stability policies of the European, North African and Sahel powers in the region. Denmark has a unique position as a European small state with a broad portfolio within the development sector in the Sahel, as well as committed participation in anti-terrorism campaigns and peace-keeping there. In recent decades the Danish government has ensured that its engagement is well-aligned with broader European strategic priorities in the region. Most recently, this has implied that the objectives for Denmark’s engagement there are increasingly being defined in terms of anti-terrorism and the control of migration.

In this spirit, Denmark’s most recent foreign-policy strategy from June 2017 contains pledges to continue its military contribution to Operation Barkhane, the French anti-terrorism coalition in the Sahel, as well as MINUSMA, the UN stabilization mission in Mali. In 2018, this was further expanded with a Danish pledge to support the G5-Sahel Platform. In parallel, the government has promised to continue prioritizing the Sahel region in its economic, social and political development assistance program and its global stabilization efforts.

The priority the Danish government gives to security and development provision in the Sahel region should not be seen as a reaction to any direct threat to Denmark. Most of the jihadist groups operating in the Sahel primarily focus their attention on local authorities and rivals. Those who actively target international actors tend to look for major European countries – in particular France – rather than Denmark. Moreover, Denmark is not a major recipient of undocumented migrants from either the Sahel region or sub-Saharan Africa, who are traditionally drawn to larger European countries like Italy and France instead. In sum, this means that Denmark is relatively free to decide where and how it engages in the Sahel.

While a small Scandinavian state cannot force the North African powers to engage more actively in handling the challenges and threats from the Sahel, Denmark’s size may give it a strategic advantage in international and regional diplomacy. In contrast to Germany, which may have trouble convincing France that it should be in charge of a diplomatic effort to bring together the North African and Sahel powers, Denmark does not pose a threat to French hegemony in the region. In combination with Denmark’s long-term involvement in stabilization efforts, humanitarian assistance and economic and political development in the Sahel, Denmark may have a good basis for taking a more active role in regional and international diplomacy.