Energy as a weapon - decoding blackmail tactics in Europe

Energy blackmail in Europe

In legal terms, blackmail occupies a paradoxical space, somewhere between lawful actions that should be treated as a crime and non-criminal ‘hard bargaining’. Blackmail involves threats to inflict embarrassment or financial loss unless certain demands are met. Put simply, it is the act of extracting money through extortion, employing techniques such as threats, violence or abuse of authority.

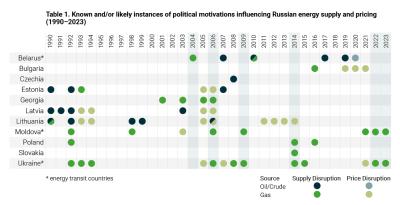

■ Energy blackmail has been frequently employed against European countries for economic and political reasons since the 1990s.

■ The shift in the EU energy policy towards Russia since 2022 deprived the latter of much leverage in terms of employing the energy blackmail tactic.

■ The practice of weaponising strategic resources extends beyond energy, increasingly encompassing sectors like cyber.

Energy blackmail follows a similar rationale. Although it lacks an established definition, energy blackmail (or energy weaponisation) can be understood as a strategic manipulation of energy resources, primarily oil and natural gas, but potentially also other fuels (e.g., nuclear fuel) for political and/or economic gain. Energy blackmail can assume different forms encompassing complete or partial disruptions in supply, both implicit and explicit threats (related to supply interruptions or other issues), coercive pricing strategies (employing prices as incentives or deterrents) or leveraging existing energy debts, and asset control (e.g., influencing decision-making through ownership of critical supply pipelines).

Generally speaking, energy blackmail frequently falls into two categories: coercion and market manipulation. Coercion relates to the practice of forceful persuasion, as when the supply of strategic energy resources is made conditional upon the fulfilment of some political or economic ultimatum. Market manipulation involves the deliberate interference with the free and fair operation of the market, creating artificial appearances or misleading impressions regarding the price and market conditions for various products, securities, commodities or currencies.

In the energy sector, this often pertains to the strategic manipulation of prices for specific - often political - gains. The success and impact of energy blackmail depend heavily on its context. Russia’s strategic weaponisation of energy in Europe - evident since the early 1990s - was made possible by a range of factors. These included Moscow’s geopolitical considerations rooted in the Cold War rationale, the concentration of strategic energy resources in Russia, a complex network of dependencies created by the pipelines connecting former Soviet/satellite states with Russia as well as with each other, and the limited institutional and economic capacities of the newly independent states. The period following the collapse of the Soviet Union marked a significant political transition in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) as countries aimed to establish market economies despite their institutional weaknesses. This left them particularly vulnerable to Moscow’s use of energy exports as a foreign policy tool, as the Kremlin’s direct political and military control of their ‘near abroad’ was masterfully being replaced with non-military means.

In the early 1990s, however, Russia frequently resorted to coercion. For instance, shortly after Lithuanian independence was restored on 11 March 1990, President Mikhail Gorbachev issued an ultimatum, demanding its annulment. The lack of Lithuanian compliance resulted in a 78 day economic blockade, which completely halted oil deliveries to Lithuania and led to an 84% decrease in gas supplies, together with the disrupted delivery of around 50 other products and materials. Moreover, Gorbachev threatened retributive actions towards the fellow Baltic States, warning of severe consequences should they choose to provideassistance to Lithuania. Thus, in the pivotal narrative of political independence, energy blackmail stood out as a critical element, significantly influencing the dynamics of this struggle. Over the years, the Russian approach to market manipulation became increasingly subtle and often challenging to identify. Many of its instances were easily misconstrued as routine market fluctuations, inflation or other common economic phenomena.

Nevertheless, in 2018, in response to the antitrust investigation, the European Commission imposed binding obligations on Gazprom to enable the free flow of gas at competitive prices in CEE. Its conclusions noted that unfair prices might have been imposed on Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Indeed, the conclusions only reaffirmed the issues that Lithuania addressed to the EC Competition Directorate back in the spring of 2011. In 2019, Bulgaria resumed antitrust proceedings against Gazprom, as the country became subjected to the highest gas prices in Europe. Multiple CEE states claimed the ‘highest paying country’ title over the years. Seeking to fortify its economic resilience, the EU introduced a new legal tool in October 2023 against ‘Economic coercion by third countries’.

It is critical to recognise that the Russian capacity to manipulate gas prices has been significantly aided by its strategic implementation of a discount policy. For instance, after paying below-market prices for Russian gas imports for many years, Ukraine found itself in a dispute with Gazprom over price increases on a number of occasions. Although raising gas prices to market levels is not in itself controversial, such disputes would typically coincide with political developments in Ukraine that contradicted Moscow’s interests. Multiple similar incidents have been recorded across the post-Soviet space, including Belarus, Moldova and others.

Countering energy blackmail

Energy blackmail ceases to be effective once states start to anticipate and counter potential coercion proactively. As such, multiple energy projects have been recently developed, especially in the CEE region, where post-Soviet infrastructural lock-ins were most prominent, making supply routes hard to diversify. LNG terminals in Lithuania (2014) and Poland (2016) and new energy corridors, as between Estonia-Finland (2019) and Lithuania-Poland (2022) along with earlier and upcoming gas connections, showcase a unified and strategic shift towards European energy independence. The weaponisation of energy supplies by Moscow against many Member States following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 prompted the EU to further increase the resilience of its energy system by greater diversification, tackling of bottlenecks, phasing out Russian fossil fuels, accelerating the green transition and increasing energy-saving measures across the EU.

Together, these measures have reduced the Russian capacity to wield energy as a strategic weapon. However, the growing digital interconnectedness of the European energy infrastructure introduces new vulnerabilities, highlighting the complexity of modern energy security challenges. Whereas gas and oil markets are typically dominated by a few powerful players and driven by state interests, threats emerge in the cyber domain from a varied mix of actors - from individuals and groups to states and state-sponsored entities.

Digital dilemmas and energy security

The increased interconnectedness of energy systems is meant to improve the integration and optimisation of energy resources. Smart grids and Internet of Things (IoT) devices leverage high interconnectivity to adapt to energy demands with unprecedented efficiency, propelling us towards a renewable energy future. However, digital integration also expands the potential attack surface for cybercrimes and complicates the security efforts to protect them. With each additional device or communication system incorporated into the power network, the potential for unauthorised access grows, as each device can serve as a gateway for cyberattacks. Such vulnerabilities pose significant risks, as a single cybersecurity breach could trigger widespread grid failures or compromise sensitive data.

The public does not fully grasp the extent of cybersecurity threats, as major breaches frequently go unreported or undetected. However, evidence suggests a worrisome trend: Cyberattacks on utility services have increased since 2018, with a significant uptick in 2022 following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Moreover, according to the recent assessment by the Danish EnergiCERT, up to 65% of the cyberattacks against the European energy sector since 2015 were ransomware attacks. Ransomware - a type of cryptovirological malware - operates by encrypting files on the victim’s system, rendering them inaccessible. These files are ‘held hostage’ while the perpetrators demand a ransom in exchange for the decryption key, which can restore access to the blocked personal data. Ransomware attacks across the European energy sector have impacted supply companies, gas distributors, refineries, wind turbine producers, wind-farm operators and prepaid electricity services. These cyberattacks have disabled wind-farm controls, disrupted prepaid meters and caused data breaches.

Like other European countries, Denmark experienced significant attacks, as when the control systems of 22 energy companies were compromised in May 2023, forcing many into ‘island mode’ operation. Amidst rising attacks, the financial toll of a single data breach in the energy sector hit an unprecedented EUR 4.33 million in 2022. This stark reality highlights the urgency to strengthen cybersecurity defences. While the EU adoption of the Cyber Solidarity Act in April 2023 marks a significant advance in its cybersecurity efforts, recent events underscore the continuous necessity for robust and evolving cybersecurity measures.

Beyond blackmail: Securing European energy landscape

The weaponisation of energy in Europe illustrates how strategic resources can be utilised in political power games. Potential blackmail is by no means confined to the energy sector and has also been employed in other sectors. In the energy sector, the relative success of the EU in reducing its dependence on Russia since February 2022 has deprived the latter of much of its leverage. However, increasing the resilience of the European energy system necessitates both heightened security measures and learning from past lessons about the pitfalls of overdependency.

Hence, several steps can be undertaken to further counter energy blackmail in the future:

Diversification: Diversify current supply routes and avoid overdependencies on singular energy resources and technology suppliers (e.g., renewable energy technology from China).

Self-sufficiency: Accelerate the deployment of low-carbon energy, cut energy demand and improve energy efficiency measures.

Innovation: Increase funding for the large-scale development of new energy technologies (e.g., green hydrogen, carbon capture and storage).

Contingency planning: Develop robust contingency plans for efficient responses to energy supply and infrastructure disruptions.

Cyber resilience & network management: Embrace the EU Cyber Solidarity Act, integrating the Cybersecurity Shield and Emergency Mechanism, along with thorough log collection, network segmentation and consistent vulnerability scans for enhanced cybersecurity and swift EU response.

DIIS Experts