Caught between a nuclear past and a fish farm future

“When the French departed, they left us in the dark”

Anthropologist Lis Kayser heard this sentence – or variations of it – many times during her stay at Hao, a French Polynesian atoll that once housed a major military-logistical base supporting the French nuclear testing programme in the Pacific.

However, it was only well into her stay that she realized that the ‘dark’ the Hao population referred to was not just a figurative metaphor for how the abrupt withdrawal of the French military presence had left the small atoll wondering in bewilderment what would come next: the French had quite literally left the small island ‘in the dark’. When the last military personnel returned to France in 2000, they pulled the plug that had provided free electric light to Hao for over thirty years.

“Clean” tests and "beautiful" mushroom clouds

Under the French Center for Experimentation in the Pacific (CEP), French Polynesia was ‘nuked’ 193 times from 1966 to 1996. France did not sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963 when the other nuclear superpowers at that time, the US, UK and Soviet Union, pledged to stop nuclear testing in the atmosphere. Accordingly, in 1966 the then French president, Charles de Gaulle, allegedly remarked ‘It’s beautiful!’ when he witnessed a massive mushroom cloud rise over French Polynesia, polluting not only the nearby islands and atolls, but also other countries as far away as New Zealand and Peru.

It was only after local and global protests that France stopped atmospheric testing in 1974, but it continued testing underground, claiming for decades that its tests were ‘clean’. In 1996 the last nuclear device was tested on the French Polynesian atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa.

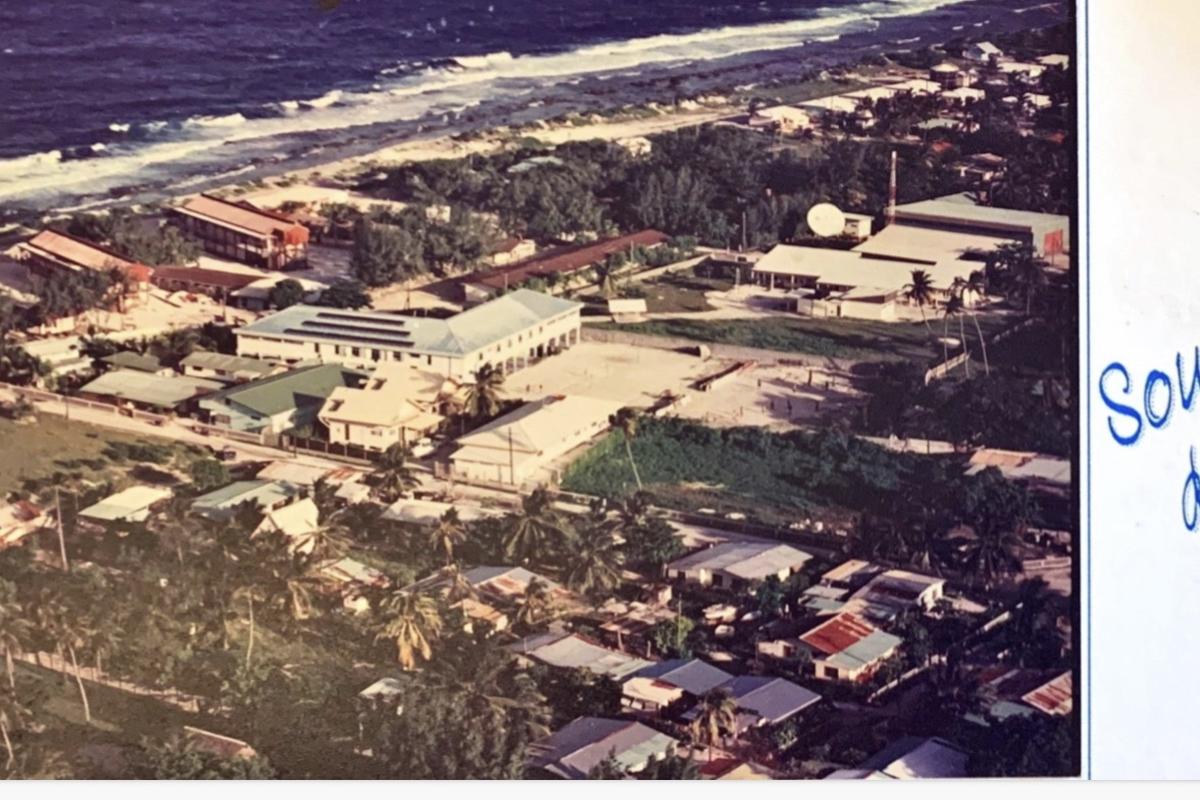

A small but pivotal site for the CEP was the atoll of Hao in the Tuamotu archipelago. Despite being a coconut tree-filled, sunny, beachy island, Hao really had only one main quality for the French – its length. The harp-shaped atoll was long enough to build a three-kilometre airstrip on it, and this simple fact – as well as Hao’s strategic location between France, Tahiti and the two test sites on the Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls – led the French to decide to build their military base on this undisturbed atoll in the middle of the South Pacific. Ultimately, the presence of the French military would change the lives of the people on Hao for decades.

■ For thirty years, from 1966 until 1996, the French military tested 193 nuclear devices on the remote, uninhabited atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa, located 1,000 kilometres southeast of Tahiti, the main island in French Polynesia.

■ 46 of the 193 nuclear devices were tested in the atmosphere, contaminating French Polynesia with radioactive fallout.

■ Data released by the French Polynesian Ministry of Health in 2018 shows a steady increase in the number of radiation-induced diseases, with 93 new cancer cases reported in 1992, compared to 467 in 2017.

■ Thousands of French military and technical personnel settled on Tahiti, as well as on the two testing sites and numerous nearby islands (including Hao), causing the population to increase by 250 percent, and dramatically changing French Polynesians’ everyday lives.

■ France’s nuclear testing policy has faced a lot of local and global criticism. 24 years after the last test, this anti-nuclear attitude is still very common on Tahiti, especially among pro-independence politicians, anti-nuclear NGOs and people suffering from radiation-induced illnesses.

■ Only in 2010 did France pass a law authorizing financial compensation for military veterans and civilians whose cancer could be attributed to nuclear testing. Only around twenty of approximately a thousand people who filed complaints against France have received financial compensation (source: AFP, 2018).

■ In 2013, the French declassified Ministry of Defence documents showing that French nuclear tests in the South Pacific in the 1960s and 1970s were far more toxic than had been previously acknowledged and that they had affected a vast swathe of Polynesia with radioactive fallout

A bikini and a Geiger counter

Lis Kayser arrived on the Hao atoll in the autumn of 2019. In her luggage were sunscreen, a bikini (the two-piece swimsuit famously named after another nuclear test site, the Bikini atoll, on the Marshall Islands), a lot of mosquito repellent and a Geiger counter. She had also brought with her rather clear ideas about how the people on Hao would feel about their nuclear past.

"As a European anthropologist trained to view nuclear testing as a phenomenon with adverse effects on ecosystems and human beings, I initially thought I was going there to mostly talk about the afterlife of nuclear testing, marked by residual radiation, pollution, radiation-induced diseases, and environmental injustice.”

Working on her PhD at the Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Lis is part of the project ‘Radioactive Ruins: Security in the Age of the Anthropocene’. The project explores the Anthropocene in the context of the radioactive afterlife of the Cold War and focuses on three geographical areas: the Marshall Islands, Kazakhstan and French Polynesia.

Before joining the project, Lis mostly associated French Polynesia with high-class resorts on expensive honeymoon destinations like Bora Bora. But prior to her field trip, she did extensive research on the history of French nuclear testing, the impact of nuclear testing on ecosystems and human health, and nuclear military pollution on Hao.

When she arrived on Hao, she wanted to know what all this meant for the present-day lives of the people on the atoll. But almost everyone Lis interviewed preferred to talk about the past rather than the present. And the times they wanted to talk about was not the pre-nuclear days of coconut harvesting and fishing.

"I remember being invited to my friend Gabrielle’s family for a lunch barbecue. And while I was – once again – trying to talk to them about their lives now, they continued to talk about the past, when the French military was still on the atoll. L’epoque CEP, as they called it. And I would listen politely and then try and return to the conversation about their lives now. But everything reminded them of the past – they just loved to talk about it."

After a while, Lis realized that the locals she was speaking to, though informed and in many cases sceptical about the consequences of the French nuclear testing programme, were longing for this past, this age of nuclear modernity.

Lis would often hear remarks like: "It was a whole other world. It was the golden age. On avait tout!" they remembered… We had it all!.

Mami Blue has grown old

When the French came, they build the three-kilometre long airstrip and an airport. Between the airport in the north and the Hao village of Otepa, they build a large military zone with administrative buildings, supermarkets and housing facilities.

The family Lis visited for lunch lives in the former military area, in the house of the former military doctor. And they are not the only ones living in the architectural remains of their nuclear past. Charlie, for example, lives in the premises of the former restaurant he owned during the CEP era. After he had closed the restaurant (due to the lack of clients), he decided to use the space as an extension of his house, that is located next to it, placing his wardrobe in the former dining area. Romain lives with his family in the old navy bar, where they use the former bar counter as TV furniture. Hiru and his wife Kalea live in the former water sports club.

The atoll celebrity, a transwoman called Mami Blue, once owned a lively bar called Mami Blue International, where locals and military personnel alike danced and partied every weekend. Now Mami Blue lives in a small house on the outskirts of the village, with a ‘souvenir’ from one of her former French lovers, a military hat, hanging on the wall of her living room.

The restaurants, the bars, the water sports club: they all closed when the French left, and today Hao’s inhabitants occupy the decaying buildings and treasure the souvenirs of lost times. The jewel of the island, the beautiful Mami Blue, has grown old, and the young people now have to drive their pick-up trucks into the coconut fields to play loud music – no nightlife exists anymore.

"The whole landscape reminds you of this very specific past. But it is not only that the past is so present in the architectural landscape: it is also present in peoples’ minds. Everything reminds them of the past," Lis says.

Lis realised that though people did acknowledge that "apparently we are sick" and "apparently our land is contaminated", the vivid memories of the festive life, new and modern commodities, and the comforts of the CEP era mentally outweighed their knowledge of the more invisible harms that had come from three decades of nuclear testing.

“At some point I had to comprehend that my idea of their nuclear past was completely different from their idea of the same past,” Lis says.

When the French military came, the population of Hao suddenly grew from a thousand to almost six thousand, and the military base provided work for many locals. Now the unemployment rate on Hao is 35%, and most people do not have the means they used to. Many islanders feel that there was a totally different sense of community when the French military personnel were there and everyone was always inviting everyone else over for barbeques – today many people have put up large fences around their houses, and invitations are few and far between.

"During the CEP era, life was just full of parties, bars, clubs, restaurants and water sports activities. Groceries were cheap. It was a time of fun and wealth. The French brought new cars to the atoll; they built a cinema. So very quickly, the French introduced this dream of modernity, of comfort and opportunity. And how do you go back to fishing, from one day to another, after that?"

However, a lot of the people Lis interviewed on Hao were very well aware of the price they have had to pay for this golden age of nuclear modernity: they knew that military waste and nuclear radiation have negatively impacted on humans and the environment. And they also knew that for the last twenty years, since the French left in 2000, they had still not moved on: ‘On attend’, ‘We are waiting’, they kept telling her.

"These years are often just referred to as ‘after CEP’, and most people find the present hard, boring and dreary. There are no jobs, and the island is badly maintained,’ she says.

■ French Polynesia has the status of an Overseas Collectivity of the French Republic.

■ Papeete, located on Tahiti, is the capital. Almost 70% of French Polynesia’s population is living on Tahiti.

■ The Hao atoll is one of 118 islands in the South Pacific that make up French Polynesia. Out of the 118 islands and atolls, 67 are inhabited.

■ The dispersed islands and atolls stretch over an expanse of more than two thousand kilometres.

■ French Polynesia’s economy is dependent on tourism and imported goods. However, French Polynesia also exports goods like black Tahitian pearls and high quality vanilla.

Nostalgia and the loss of a future

Lis decided that her research should focus on the nuclear afterlife on Hao through the prism of nostalgia. Nostalgia, like that Lis encountered on Hao, can shape people’s understandings of the past, make them cope with present challenges and act towards a future yet to come. Lis perceives the nostalgia on Hao as a longing for what is lacking in the present time of socio-economic and political uncertainty.

"Nostalgia is often triggered when people find themselves in a current situation that is unstable, when an abrupt break with the past has disturbed the continuity of life. And it seems to me that the moment the French military left Hao in 2000, when they literally pulled the plug, this marked the end of what are seen in retrospect as the more stable, ‘golden’ times of the French military presence, when people had lucrative jobs, electricity and running tap water were free, and the future seemed bright and predictable. These are the times that the people on Hao now feel nostalgic about," Lis says.

With her research, she hopes to highlight the complexity of the nuclear afterlife.

"Obviously, the Hao population has suffered from the ecological and health consequences of decades of nuclear testing carried out by France. But at the same time, they also benefitted from it in some ways and at some points. And they remembered their lives as very nice and happy-go-lucky. Now they feel guilty, to some extent, for what they have done to their atoll and to future generations. Many people feel torn by having both worked for and participated in the testing programme, while also being affected by radiation, disease and economic dependence."

The ruination of dreams

The DIIS research project “Radioactive Ruins” not only deals with the material ruination of the areas affected by nuclear testing. On Hao, it also deals with the ruination of dreams.

"When former French President Charles de Gaulle delivered a speech in French Polynesia in the 1960s, he said something along the lines of: “We give you the atomic bomb, this is a gift to the people, you have a chance to work with us and to make France and the overseas territory even more powerful.”’

In return, France would give the people on Hao an economic lift and a vibrant, ‘modern’ island life, with lucrative jobs, bars and nightclubs, as well as a promising future marked by a striving for a nuclear utopia.

"France realised its dreams of nuclear modernity. It went as fast as it could with its nuclear programme and continues to be a nuclear superpower. Its nuclear dreams became a reality. But the people on Hao? What happened when their dreams could not be sustained? When the French departed, they started to realize that their idea of the future had relied on these dreams of a nuclear utopia, and now that they could not be realized, they slowly turned into nostalgia."

Will nuclear past become fish farm future?

Something that often came up in the conversations Lis had with people on Hao was the plans for a new fish farm on the atoll. At first, Lis did not show too much interest in the project: a Chinese company with 300 million dollars to spend would turn the Hao lagoon into a massive fish farm. The population on Hao, however, were excited. Someone had already opened the atoll’s third supermarket in anticipation of the Chinese coming to Hao in large numbers.

"At first I did not understand why they were referring to the Chinese fish farm project when I asked them about how contemporary everyday life on Hao is affected by the aftermath of nuclear testing. Later, I realised that the French nuclear testing programme and the Chinese fish farm project had more in common for the local population than I expected," Lis says.

She elaborates:

"Their nuclear military nostalgia and their anticipation of future economic projects are local ways of coping with the socio-economic challenges of the present. The French nuclear-testing programme is the point of reference or ‘guiding star’ for future development projects in French Polynesia, including the Chinese fish farm project on the Hao atoll. The Hao population, like many other French Polynesian citizens and politicians, link economic development and, consequently, social well-being with the French nuclear-testing programme."

Many people on Hao are therefore hoping that the Chinese will arrive and create a second "golden era". Where jobs are plentiful and everyday life will look more like it did, when the French were there.