What needs to change for green funds to be truly green

- There is still a lack of agreement about what defines the burgeoning environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds, making them prone to greenwashing.

- While ESG funds may in theory have a sustainability impact by divesting from fossil fuel firms or exercising shareholder pressure, the current design of most ‘green’ investment funds does not make proper use of these mechanisms.

- Regulation needs to create minimum standards to ensure that green funds actually have a sustainability impact in the real economy.

Green investment funds are growing rapidly. However, their impact on climate change mitigation and sustainability remains unclear. Recent research has identified key shortcomings that need to be addressed in order to reduce greenwashing and make these funds truly green.

Green finance is playing an ever more prominent role in recent years. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds, which constitute a key pillar of green finance, saw record inflows of hundreds of billions of US-dollars in recent years, primarily by retail investors. Essentially, these ‘green’ funds are integrating environmental, social and governance criteria, such as greenhouse gas emissions, labour rights and gender diversity into their investment strategy. They claim to invest less in the stocks of firms that are highly polluting or have bad governance practices, and instead buy the shares of corporations that appear to be more sustainable.

In industry and policy debates, ESG funds are often cited as advancing the promotion of sustainability and helping to address climate change. However, the ESG concept, its underlying criteria, and its potential effects are highly controversial. Many critics see ESG primarily as ‘window dressing’, with no significant positive impact – either for the environment or for investors and employees.

Broad definitions of ESG

A crucial problem with ESG is that nobody knows how big this type of investing really is: there is no internationally accepted definition, so estimates of ESG assets vary widely. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), sustainable funds reached a total volume of $35.3 trillion in 2020 – a stunning 55% increase since 2016. According to this calculation, ESG would allegedly account for one-third of all professionally managed financial assets.

This number is extremely high because GSIA includes the very ambiguous category ‘Broad ESG’ in its definition. In practice, managers of ‘Broad ESG’ funds merely take environmental, social or governance issues into consideration – but they do not have to act upon them. Their investment decisions thus often deviate very little from regular funds.

When you apply any kind of hard criteria, the volume of identified ESG assets shrinks significantly. A recent episode makes this point exceedingly clear: the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, an industry organisation in the US, modified their methodology. This almost halved the amount of funds considered to be ‘ESG’ from $17.1 trillion in 2020 to $8.4 trillion in 2022 – even though most sources reported record inflows into ESG funds during that time.

Morningstar, due to the exclusion of many ‘Broad ESG’ funds, estimated the value of ‘sustainable’ funds at just $3.4 trillion in March 2021 – less than onetenth of the GSIA estimate. However, by September 2021, Morningstar tightened its criteria and downgraded that estimate to $2.03 trillion. Given this significant conceptual ambiguity, there are extremely different estimates concerning the size of ESG funds (see table).

Greenwashed or truly green?

The widely varying estimates for the size of ESG investing suggest that greenwashing is a big potential problem for the ESG industry. G reenwashing may be intentional to gain a market advantage, but it may also be unintentional due to the lack of a widely accepted definition of ESG.

One of the key questions is whether ESG merely reduces environmental, social and governance risk for investors (‘input ESG’), or whether these funds can have a sustainability impact (‘output ESG’). Sustainability impact can be defined as a positive change in companies’ behavior and real-world outcomes caused by ESG funds. Only by ha ving such an impact would ESG funds advance sustainability and thus be truly green. However, this question remains unanswered because the role of the transmission mechanisms through which ESG funds can ha ve a sustainability impact on firms has been largely neglected by research and regulation so far.

Recent research has found that two mechanisms are vital for ESG funds to have a sustainability impact by creating positive change in the real economy: (1) shareholder engagement and (2) capital allocation. Shareholder engagement includes both how fund managers exercise the voting rights attached to their shares at annual general meetings of companies, and how they influence the manage ment of companies via public campaigns or in meetings. Fund managers regularly vote on proposals that influence the sustainability of companies, such as the adoption of net-zero emissions strategies or the election of sustainability-minded board members.

One of the key questions is whether ESG merely reduces

environmental, social and governance risk for investors, or whether these funds can have a sustainability impact.

Capital allocation can also advance sustainability if fund managers do not invest in fossil fuel firms (what is called ‘divestment’) but channel their investments towards companies that have reduced greenhouse gas emissions. This mechanism implies that ESG funds need to deviate substantially from conventional funds. Conventional as well as ESG funds, however, often closely track so-called benchmark indices, such as the A merican S&P 500 or the British FTSE 100, which include big fossil fuel firms.

It is important to note that ESG funds only buy the shares that firms have issued in the past and are thus not able to directly invest in any new projects that advance sustainability. The only way ESG funds can create positive impact is indirectly via the firms in their portfolio. However, if shareholder engagement and sustainable capital allocation is not used effectively, ESG funds are nothing more than vir tue signalling unable of generating any meaningful sustainability impact in the real economy.

Not enough Dark Green

Contrary to the intuitive expectations of most people, the vast majority of ESG funds do not define and commit to a strategy of voting their shares to advance sustainability. Research has even found some instances in which ESG fund managers ha ve voted with the management of big oil firms against proposals filed by shareholders that sought t o reduce greenhouse gas emissions. ESG funds also do not systematically use shareholder e ngagement to create a sustainability impact in the firms they have invested in. As a result, there is a clear ‘ESG shareholder engagement gap’ which means that this potential transmission mechanism is currently not being used effectively.

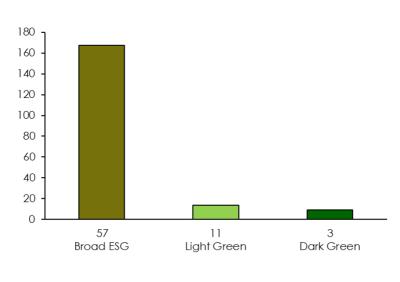

Using Bloomberg data, covering $793 billion in sustainable fund assets and thus applying a relatively strict definition of ESG, a recent study has analysed the capital allocation of ESG funds. The study finds that most ESG funds de viate only slightly from their (non-ESG) benchmark indices, which mostly include fossil fuel firms. Our resear ch classifies the subset of ESG funds ($190 billion) that are directly tracking ‘sustainable’ indices into three segments: Broad ESG (little difference from conventional funds), Light Green (low sustainable capital allocation) and Dark Green (very sustainable capital allocation). Only three funds are Dark Green funds (see figure). In our sample, less than $10 billion are included in funds that we consider ha ving a substantial sustainability impact. Hence, there is a large ‘ESG capital allocation gap’.

Regulation in both the US and the EU has recently begun to address greenwashing with the aim of increasing the transparency of ESG funds through better disclosure. Increasing the transparency of ESG funds is certainly useful but will not be enough to bring about significant change concerning sustainability issues. Most of these regulations do not specifically address the two main potential transmission mechanisms via which ESG funds could have a positive impact in the real economy, namely shareholder engagement and capital allocation. Hence, minimum standards for these two transmission mechanisms should be created to ensure that ESG funds do in fact advance sustainability. Only then can ESG funds be considered truly green.

This policy brief is based on the DIIS Working Paper ‘Mind the ESG gaps: Transmission mechanisms and the governance of and by sustainable finance.’

The views and opinions expressed by the authors do not represent the official position of the Deutsche Bundesbank.