Trump's troops

A strategic and ideological alliance has emerged between the American and Central Eastern European Right. Replacing Berlin with Warsaw and Budapest may have profound implications for policy, and for NATO’s consensus on Russia.

■ Moving US troops from Germany to the Baltic Sea Region runs deeper than Trump telling Merkel to pay up. Under Trump, US trade, diplomacy and foreign policy coordination with key CEE countries has dramatically expanded.

■ Tying this US-CEE alliance together is not just transactional politics, but a shared ideological agenda around the crisis in and defence of ‘Judeo-Christian Civilization’.

■ If continued, this agenda will have radical implications for key NATO areas of concern, such as the Middle East, counter-terrorism, human rights and migration.

■ Above all, it will challenge the NATO consensus on how to deal with Russia.

The US is currently planning to reduce its current deployment of troops in Germany from 36,000 to 24,000. This radical reduction was confirmed by US Secretary of Defense Mark Esper on July 29, and according to the Pentagon it will take ‘months to plan, years to execute’. What has been signalled so far, though, is that nearly 5600 of the troops removed from Germany will go to other European countries – Italy has been mentioned, and on August 15, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo signed a deal with Poland to add another thousand to the 4500 US troops already there. The remaining 6400 troops to be pulled out of Germany will be returned to the US, to become part of a rotational deployment into the Black Sea and Baltic regions. Why?

A reprisal over German defence spending?

According to the Pentagon itself, shifting forces eastward is a strategic move intended to increase the deterrence of Russia. However, most observers read the reduction as political, even personal, a Trump-classic reprisal against Angela Merkel, who has snubbed his agenda more than once. Most importantly, this has been on the issue of defence spending, where Germany continues to fall short of the NATO aim of 2% of GDP. ‘We’re reducing the force because they’re not paying their bills’, Trump has stated. The fact that Merkel also declined Trump’s invitation to a G7 meeting in Washington during the Covid19 lockdown and her reluctance to resist Russia regarding the Nordstream 2 pipeline are also likely parts of the equation.

And yet more than a gut reaction by an impulsive president is at work here. To begin with, Trump’s reshuffling of US troops perpetuates the perception of a rigid and rule-obsessed ‘Old Europe’ – already put down by the younger Bush’s administration – and an attraction to a flexible and expedient ‘New Europe’, sometimes invoked by the Obama administration too around such issues as counter-terrorism and emerging security technologies (for instance, drones). This attraction has now gained more serious momentum, as the new American Right finds it has common ground with national-conservative governments in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

A US-CEE ‘Judeo-Christian’ Alliance

Trump proclaimed the existence of that common ground when he gave his first European foreign-policy speech in Warsaw – not Berlin, Paris or London – on 6 July 2017. ‘Poland’, he said, is not ‘only the geographic heart of Europe, but more importantly…the soul of Europe’. I am here, he continued, ‘to hold Poland up as an example for others who seek freedom and wish to summon the courage and will to defend our civilization’.

Since then, Polish trade with the US, both imports and exports, has nearly doubled. Poland has purchased 32 US F-35 fighter jets and been granted a long-wished-for place in the US VISA Waiver Program. Moreover, not just Poland, which has long been a spender on defence, but also Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Romania now meet the 2% NATO goal, while Hungary, though still behind, has committed itself to meeting it in 2023. In return, Trump, who has still not been on an official visit to Berlin, hosted more than ten Central and Eastern European state leaders at the White House in 2019 alone.

Tying the alliance together is the deeply ideological vision of ‘Judeo Christian civilization’ which Trump spoke about in Warsaw.

This intensified US-CEE cooperation may appear transactional in nature – geopolitical wisdom in an era that no longer can afford to dwell on ‘values’. Yet its fuel is just that: values! Key to understanding the drive, strength and likely durability of the US-CEE conservative alliance is more than interest-based politics. Tying the alliance together is the deeply ideological vision of ‘Judeo-Christian civilization’ which Trump spoke about in Warsaw and which the Visegrad group, with Orban’s Hungary and Duda’s Poland centre stage, are pushing in the EU context too. This vision is central not just to the outlook of the US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, but of Vice-President Pence as well, a favourite future Republican presidential candidate: ‘The US and Poland’, Pence told President Duda during a Warsaw visit in 2019, ‘are tied together by commitments to freedom and faith and family…were not just allies, we’re rodzina. We’re family’.

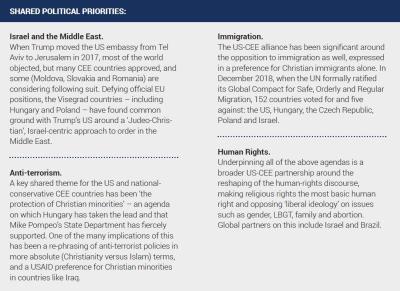

This is also a vision with specific, NATO-related foreign-policy implications. These concern:

In other words, Trump’s pull-out from Germany may be an impulsive reaction to Merkel’s postures on defence, but the mutual attraction between the US and CEE runs deep, driven by extensive financial and political ties. Although a Joe Biden administration may weaken those ties, the US-CEE alliance has become central to the Europe outlook of a post-Trump Republican Party and will remain a power factor in Congress.

Implications for NATO

What are the implications for the future of NATO? In immediate terms, the US reshuffling of its troops has provoked logistical concerns. The US European Command (EUCOM), crucial to operations in the Middle East and Africa, is currently based in Ramstein and Stuttgart in Germany. Relocating part of EUCOM to Mons, Belgium, and hence closer to NATO headquarters may have some strategic merit to it, but US partners and observers worry that the extensive and expensive German facilities cannot quickly or cheaply be replaced.

More seriously, many worry that the move will influence alliance cohesion and trust. The reduction itself has damaged an already impaired relationship between the US and Germany. Will the practices of troop rotation and flexibility force European allies to compete with each other for troops, further eroding alliance solidarity?

This worry assumes further proportions when the emerging US-CEE ideological alliance is taken into account. That alliance has not been formed in a void – it comes at a time when European politics, not least within the EU, is in turmoil. Over Brexit. And over simmering Western versus Central-Eastern Europe rifts. Such rifts have partly to do with different views on the future of Europe. Multicultural and post-national? Or sovereigntist and Christian-conservative? They also have to do with a post-Cold War process of eastern ‘democratization’ that has left countries such as Poland and Hungary with a frustrated sense of being treated with condescension, overlooked, or asked to be simple ‘copies’ by their Western European partners.

Disrupting the Russia Consensus

Pushing US troops and attentionfocus eastwards will likely exacerbate that split, thus upsetting alliance cohesion. Perhaps most crucially, though, it will challenge the NATO consensus on Russia. Two overlapping and yet competing dynamics are key here, to which attention must be paid:

■ On the one hand, the US pull-back has further fuelled French and German debates over the need for greater European security autonomy. This will likely drive Western European states in the direction of more bilateral, pragmatic and ‘common ground’-oriented relations with Moscow, so that they feel on their own the incentive to muddle through compromises in relation to Russia’s geopolitical ambitions will be strong.

■ On the other hand, the US and the CEE countries, while staunchly opposed to Russia in geopolitical terms, are likely to align with aspects of Russia’s opposition to the liberal order and institutions. Poland and Hungary may have very different relationships with Russia, but they share the Judeo-Christian vision, as do Trump-style conservatives, overlapping with Putin’s conservative culture war, not with EU liberal internationalism. It is important to acknowledge the complexity or downright paradox that this creates for NATO’s foundational values.

These parallel dynamics are likely to make future NATO relations with Russia harder to predict. The US-CEE alliance will certainly want to deter Russia’s geopolitical ambitions vigorously. But will it also want to align with standard EU visions of what the West is or needs? Hardly. In other words, whereas Western Europe may feel forced to come down hard on deterring Russia, but be called to stand its ground when it comes to softer liberal-values issues ranging from technology and surveillance, to gender, human rights, migration policy or development aid, a US-CEE conservative alliance may want to do the exact opposite.

Viewed from this perspective, a more symbolic power attaches to the question of NATO location. Whether US soldiers leave Germany for Italy, Poland, or the Baltics may read like an issue of logistics and practicality only. At stake, though, is also memory and hence identity: the untying of NATO’s soul from its specific historical origins and from the distinctive lessons that German soil spells out. Keeping NATO forces on German soil – an eternal reminder of what happened the last time a struggle for civilizational grandness tore Europe apart – may be a point in its own right.

For further background on the growing US-CEE relationship, see my report with Minda Holm, published by NUPI earlier this year: https://www.nupi.no/nupi_eng/Publications/CRIStin-Pub/Brothers-in-Arms-and-Faith-The-Emerging-US-Central-and-Eastern-Europe-Special-Relationship