The promises and perils of law-making as the way to strengthen societal resilience

- There is an underlying mismatch between the dynamism of resilience and the static nature of laws.

- Resilience entails the capacity to bounce back flexibly from crises. Laws should be formulated so as to nurture such flexibility.

- Democratic accountability might be at risk when laws are used in the quest for strengthened resilience.

Since 2014, Ukraine has been the target of widespread Russian cyber-attacks against military and civilian targets, such as ministries and banks. At the same time Russia trained and supported rebels in their fight against the Ukrainian army in eastern Ukraine. After eight years of grey zone conflicts, Russia decided in February 2022 to launch a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine, marking the start of the first major interstate war on European soil in more than two decades. But Russia did not stop its influence operations in other countries, such as the Baltic states, where it spreads disinformation and aims to employ Russian-speaking minorities to achieve its strategic purposes.

The international security situation is changing rapidly. China, and especially Russia, increasingly make use of assertive and aggressive behavior that war studies scholars have labelled grey zone conflicts. Exploiting the distinction between war and peace enshrined in international law, these activities make use of economic coercion, political influence, unconventional warfare, and information and cyber operations. They aim to achieve strategic effects, exploiting the open, liberal societies of democracies, while remaining below the threshold of armed conflict. In doing so, they challenge NATO’s conventional military supremacy.

To counter these grey zone activities, NATO and its member states have turned towards the concept of “resilience.” In the updated NATO Strategic Concept from June 2022 resilience is seen as critical to all of NATO’s core tasks. It also serves as the new compass for EU policies. But what is (societal) resilience and how does one achieve it?

Resilience refers to an entity’s ability to resist, respond to, bounce back from, and/or transform under shocks or crises. The idea is that high levels of resilience secure states and their societies against the effects of attacks, wars, epidemics, or natural disasters by mitigating risks and vulnerabilities and ensuring the continuation of core functions. It thus relates to the internal characteristics of states and their societies and requires what has been dubbed a “whole-of-government” and “whole-of-society” approach.

Through grey zone activities Russia and China aim to achieve strategic effects, exploiting the open, liberal societies of democracies, while remaining below the threshold of armed conflict.

While the calls for improved resilience are ubiquitous and there is agreement on the need for a comprehensive approach, there are fewer concrete examples showing how resilience can actually be strengthened. Engulfing sectors of society that do not traditionally fall under security policy considerations, grey zone conflict requires emergency management agencies and other authorities to take a broader perspective on preparedness for crises and even war. In their attempt to improve resilience, and aside from softer, more practically-oriented approaches such as leaflets containing recommendations for stockpiles, governments often turn to the one tool they have readily available to implement their policies – national laws. This is illustrated for example in the policies addressing the COVID-19 pandemic: vaccines and tests were mandated, societies put under lockdown, and supply chains changed. The Baltic states’ responses to Russian grey zone threats are also heavily based on national laws; they include, for example, an Estonian language requirement as a necessary condition for citizenship, general bans of Russian-language websites and media channels, a prohibition on public expressions of support for Russia or the country’s aggression against Ukraine, and Lithuania cutting off all energy imports from Russia. (For a more elaborate account see the DIIS report Energy Security in the Baltic Sea Region)

The problems of creating resilience through law

Creating resilience through law, however, brings with it three challenges that will need to be understood and addressed if approaches to strengthening societal resilience are to succeed.

First, there is an underlying mismatch between resilience and law. Resilience requires dynamic adaptation, the ability to adjust and respond in a flexible manner. Law on the other hand is much more static. Laws can be changed, of course, but that mostly happens in response to a situation that has already shifted. Laws also establish a strict dichotomy of legal/illegal, while the required flexibility for achieving resilience entails multiple pathways. Furthermore, laws are supposed to establish security and order by preventing certain behaviors or threats, whereas resilience accepts the existence of a threat and addresses how to handle that threat rather than trying to prevent it. Highlighting these contradictions already raises the question as to whether laws truly are the appropriate tool for achieving resilience.

Second, achieving resilience through law requires a delicate balance to avoid overregulation as well as gaps or partial, insular approaches. To be efficient, regulations for protecting critical infrastructure or preventing the spread of disinformation require agreed-upon comprehensive definitions of these core terms. Otherwise, such laws may overreach – or alternatively create gaps in the resilience set-up. This is a problem in Denmark, for example, which lacks a legal definition of critical infrastructure, or in Estonia, where laws prohibiting hooliganism were used to prosecute those spreading fake news about COVID-19. Similarly, the decentralization of crisis preparedness, such as enshrined in the Danish law on sectoral responsibility, is a double-edged sword: it is a practical approach that places responsibility with the relevant societal sector, where the necessary expertise, knowledge, and interest lie in the first place. However, it also hampers the coordination and integration of efforts, and often does not reflect the nature of today’s complicated crises and threats that span the different sectors of societies.

Achieving resilience through law may result in undermining the liberal, democratic values we are trying to protect and which are part of our societies´ core functions.

Third, achieving resilience through law may result in undermining the liberal, democratic values we are trying to protect and which are part of our societies´ core functions. Two important questions must be answered in this respect: first, whose resilience should be strengthened, and second, whether the laws or other tools will indeed have the desired effect or might have negative second-order effects. Examples of the latter are manifold: increasing surveillance in the digital and physical world, limiting the freedom of association, and/or the freedom of speech. Thus, it is not only the relationship between law and resilience but also that between democracy and resilience that is not straightforward. Attention must be paid to the specific consequences of laws aimed at strengthening resilience. Different groups may be affected differently, and laws to increase resilience – such as targeting disinformation by prohibiting all Russian-speaking media – might result in the further stigmatization of certain societal groups, sectors or industries. Consequently, societal divisions become larger and might end up pushing Russian minorities further into Moscow’s arms, decreasing societal resilience instead of strengthening it. This needs to be avoided.

What can be learned from this?

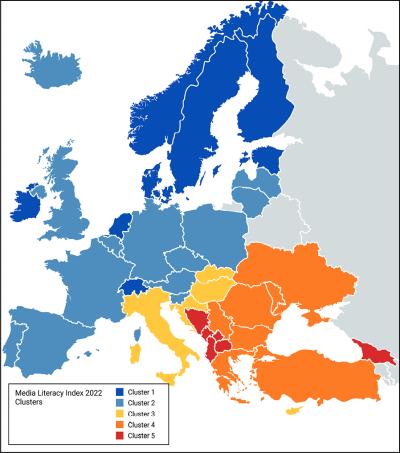

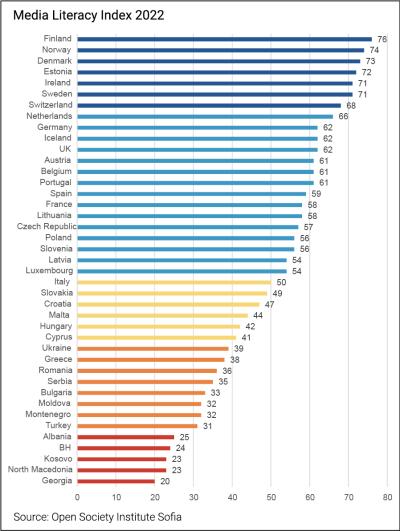

There is a risk that attempts to increase resilience through law may fall short, and possibly worsen divisions in society. What is needed is a much broader approach to resilience creation than legal regulation. Resilience aims to ensure that society’s core functions are protected and can continue in a crisis, but it must also protect the underlying values these functions are built upon. It is also a mindset and a culture. Legal regulation will remain a crucial component of approaches to strengthen resilience, but it also requires societal trust which allows the government to overcome problems regarding information distribution and sharing, as well as the monitoring and enforcement of resilience efforts, and means citizens are more prone to follow government instructions and procedures. It requires societal awareness, including from the state actors. In this respect, Nordic and Baltic states can learn from each other and teach third states: The Open Society’s Media Literacy Index 2022, which includes a measurement of societal trust, ranks Finland, Norway, Denmark, and Estonia as the top four countries out of 41, while other Baltic Sea region states fare less well: Germany is #9, Lithuania #17, Poland #19, and Latvia #21. The worst performing countries are in South-eastern Europe and the South Caucasus - regions heavily targeted by Russian influence operations.

Finally, resilience requires both institutional memory and flexibility. These, however, do not go hand in hand, but constitute a trade-off.

Overall, building resilience requires cooperation among the political elite and strategic communication. Laws can be used to limit the spread of disinformation, to force business sectors to plan for crises, and to implement emergency procedures, but laws cannot necessarily account for how different groups will be affected differently and thus require different types of support to increase their resilience. Additionally, laws cannot create societal trust or cohesion among the political elite. Laws comprise only one tool in a much larger toolbox for resilience creation – an important one, but one that is not sufficient on its own.

Dr. Amelie Theussen is an associate professor at the Centre for Arctic Security Studies and Institute for Strategy and War Studies at the Royal Danish Defence College