The European Union can go green and lower dependencies on China

Some Western pundits see the ongoing policy push from the European Union to de-risk supply chain dependencies on China as a threat to gains from decades of economic globalisation. Others regard Chinese industrial strengths in green technologies as unbreakable and see attempts to diversify the EU’s reliance as setting back global efforts to fight climate change.

- Geopolitical risks and supply disruptions demand that the European Union not only engages in high-end research and development in advanced technologies but also urgently works down the industrial value chain to lower its high dependencies on China.

- The European Union should exploit the building blocks in critical mineral extraction and processing that it already has within its borders to resiliently manufacture clean energy technologies.

- Europe’s upstream capabilities in producing alloys and metals for permanent magnets, essential in electric vehicles and wind turbines, as well as in chemical refining for batteries, need strategic backing to withstand Chinese monopolistic pressure.

Yet, diversifying sources of critical minerals away from China and other large suppliers is a necessity in today’s volatile geopolitical climate. As well as actively pursuing new partnerships overseas to lower large dependencies on single sources, EU member states should fully harness new regulatory tools, such as the Critical Raw Materials Act, to diversify sources of critical minerals and exploit the Net-Zero Industry Act to support the production of green technologies and leverage European resources, capabilities and know-how. Contrary to conventional thinking, Europe is not starting from scratch when it comes to developing strategic supply chains in green, digital and defence technologies. Over time, there is ample potential for de-risking critical minerals to have a positive impact on the EU’s supply chain resilience and its contribution to lowering global emissions.

China’s critical mineral dominance

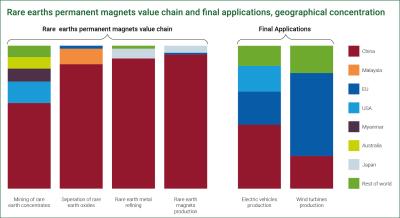

Whether it is lithium, cobalt and graphite to manufacture electric vehicle batteries, silicon for semiconductor chips, or rare earth elements for guided munitions, critical minerals are vital in green, digital and defence technologies. Yet, the EU is highly dependent on a single market, China, to satisfy many of these strategic needs.

When it comes to green industries, for example, the EU’s dependence on China is staggering. China supplies four-fifths of the EU’s solar panel needs and over 90% of its demand for rare earth permanent magnets and battery-grade lithium, both key inputs for producing electric vehicles.

Recognizing geopolitical realities

Without doubt, cutting back dependencies from these Chinese-dominated supply chains is an arduous task. Yet, there is a strategic imperative for the EU to lower high dependencies on China.

First, the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exposed the risks of overdependence on individual suppliers. With the possibility of military conflict across the Taiwan Strait blocking major trade arteries and costing the global economy trillions of dollars, the hyper-concentration of critical mineral processing and refining as well as green and digital technology manufacturing in one source makes little strategic sense.

Neither does it take a major war for supply disruptions to inflict heavy costs on global trade and business. The Red Sea conflict beginning in late 2023 and the Suez Canal obstruction two years earlier both underline the high costs of regional or single-source dependencies for Europe and the global economy.

There is also the reality that no one country -- not even China -- can alone mine, process and manufacture all the critical minerals, components and technologies necessary for the green transition. According to a recent study by McKinsey & Co., investment in critical minerals must increase to $300 billion to $400 billion a year to support the green transition. Analysts estimate that China made a record $20 billion in mining and metals investments in 2023. That is an impressive level, but it is not enough. If other major economies simply sit back and let Chinese players try to do all the work, there is a risk of supply shortages slowing efforts to address climate change.

De-risking for diversification

Neither is European leadership planning a full-scale decoupling from China-centred supply chains. While critics of de-risking see the term as overly ambiguous, open to multiple interpretations, or simply decoupling in disguise, even a cursory reading of European diversification strategies reveals specific, measured aims. For example, the EU’s agenda on critical raw materials targets securing 10% of EU needs from within the bloc and capping external dependence on any single outside nation at 65% across each stage of strategic raw material processing.

These will still be challenging targets to hit, but de-risking will help Europe lower its vulnerability to a possible Taiwan crisis and minimize Beijing’s opportunity to exploit industrial dependence for political and economic ends. In this context, it is useful to reference China’s recent move to restrict the export of gallium and germanium, metals vital for the making of semiconductor chips, followed by export restrictions on graphite, important in battery manufacturing. In late 2023, Beijing placed a ban on rare earth extraction and separation technologies, in which it is a world leader.

By cutting off these supplies and technologies, China can frustrate European efforts to develop its own green technology supply chains in the short and mid-term. But Beijing’s restrictions also underline the necessity, and indeed may even accelerate efforts, to develop alternatives, such as the recent official European support to help Swedish upstart battery-maker Northvolt compete with Chinese and East Asian market leaders.

Lessons from Japan

For Europe to develop resilience in green supply chains, it is essential that the EU and its member states act both up and down the value chain. Japan provides a model in how to develop alternative green supply chains covering mining, processing and metal-making for magnets and batteries. This effort began after China imposed a brief ban on the shipment of rare earths to Japan amid a flare up in the two countries’ territorial dispute in 2010. As a result of its policy effort, Japan’s Ministry of Economic, Trade and Industry estimates that by 2020 the East Asian country lowered its dependence on China for rare earths from 90% to 59%.

Japan de-risked from China by offering financing to Perth-based mining company Lynas Rare Earths to develop a mineral deposit in Western Australia and a processing plant in Malaysia. Japanese metals and magnet companies have also bolstered their production bases in Thailand and Vietnam. At the same time, Japan continues to account for over one-third of the global production of high-performance rare earth magnets and maintains a sizeable share of the global market in batteries for the electric vehicle industry.

Europe’s strategic building blocks

Europe may not have the same industrial basis as Japan, but it does have its own building blocks to develop its supply chains. The EU can leverage budding mining partnerships with the U.S., Canada and Australia, as well as investment by European companies in mineral-rich countries in Africa and Latin America, to accelerate the de-risking timeline. The Nordic region has untapped critical mineral potential to help satisfy Europe’s long-term demand, including graphite from Sweden. But the environmental risk created by new mines must be balanced with support for recycling and circular industrial cycles in which Europe strives to be a world leader.

There is also critical mineral processing potential in Europe. Finland refines 10% of the world’s cobalt output already. Belgium refines germanium and gallium. Estonia is home to one of the only rare earth processors operating outside China. A Norwegian company has attracted investment for another rare earth processing facility that will cover 5% of Europe’s needs using a new technology that it developed with a small amount of EU support.

One of Europe’s largest dependencies on China, according to the Rare Earth Industry Association, lies in the import of permanent magnets essential for sophisticated systems like electric vehicles and wind turbines. At the same time, Europe’s upstream capabilities in producing alloys and metals for these super magnets, as well as chemical refining for batteries, need state aid and other strategic backing to complete the supply chain and withstand Chinese monopolistic pressure.

There are sprouts of growth, however. In an effort to cut into Europe’s dependence, Canada’s Neo Performance Materials is developing a mine-to-magnet supply chain that will stretch from North America to Europe.

Change never comes easy. Breaking long-standing dependencies and remaking supply chains is a costly, complex and lengthy process. China did not, after all, build its industries overnight. But developing alternative manufacturing networks is not an insurmountable task. Europe’s de-risking plans can succeed.

This brief updates an article originally published in Nikkei Asia

DIIS Experts