Making women count, not just counting women

- Formulate a clear mandate for WPS functions in the mission that positions the WPS agenda as an integral element of NMI’s other activities.

- Support awareness-raising programmes and initiatives to transform social norms, including patriarchal gender norms and institutional socio-political constraints on female participation.

- Support the transparent qualifications-based recruitment and employment of women and prioritize the focus on inclusive work environments, both mentally and physically.

- Incorporate intersectional and masculinity perspectives in the work on WPS to avoid creating an image of WPS as a foreign-backed agenda that is only of, by and for elite women.

A priority for NATO Mission Iraq is to further the Women, Peace and Security agenda as one of the mission’s activities. This effort should focus on raising awareness of the operational benefits of equal opportunities and diversity and not just counting the number of women involved.

Adopted by the United Nations Security Council in 2000, the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) resolution 1325 sets out to guarantee men and women equal rights to participation in and influence on issues of peace and security. NATO Mission Iraq (NMI) has included a strong focus on WPS in its activities, but, as this brief argues, the effectiveness of the agenda is hampered by an unclear WPS mandate in the mission itself, as well as in the broader Iraqi context.

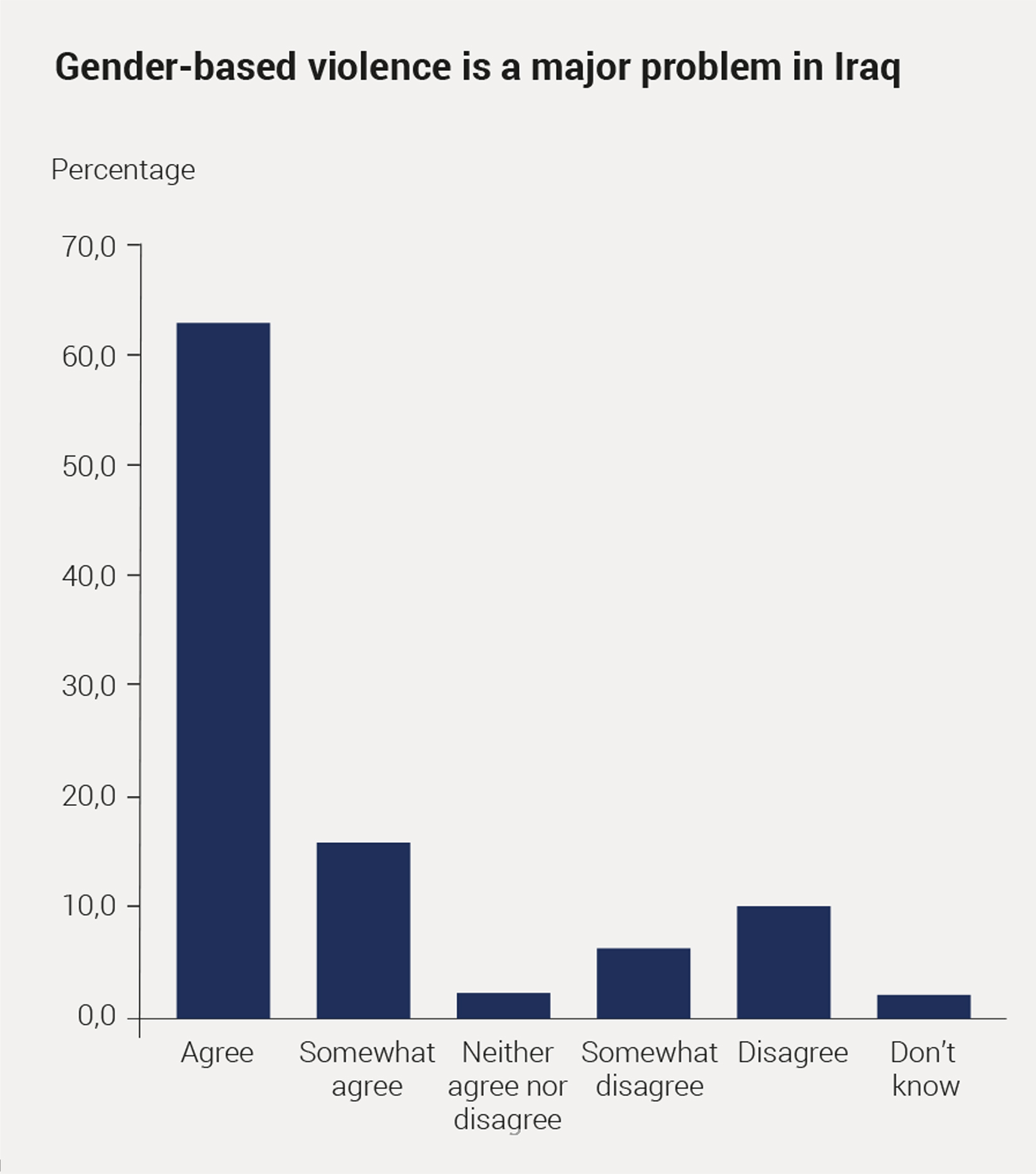

NATO Mission Iraq (NMI) supports the Iraqi Ministry of Defence (MoD) in implementing the WPS agenda, but this work is taking place within a broader context in which women face discrimination and restrictions because of their gender. There are massive issues with the protection of women, as illustrated by a recent survey commissioned by DIIS in Iraq, where 79% of the respondents agreed or somewhat agreed that gender-based violence is a major problem in the country.

However, whereas gender-based violence is viewed as a major problem, some forms of gender-based violence, such as domestic violence, are viewed as acceptable if, for example, a wife leaves her house without her husband’s permission. This is legitimized by Article 41 of the Iraqi Penal Code (No. 111 of 1969), which grants men the right to discipline their wives.

The purpose of NMI is to assist Iraq in building more sustainable, transparent, inclusive and effective security institutions and armed forces in order to improve their capabilities in fighting terrorism, preventing the return of Daesh and stabilizing the country. Denmark leads the NMI until May 2022 and is committed to contribute up to 285 personnel to the mission.

Inclusion of women in the security sector

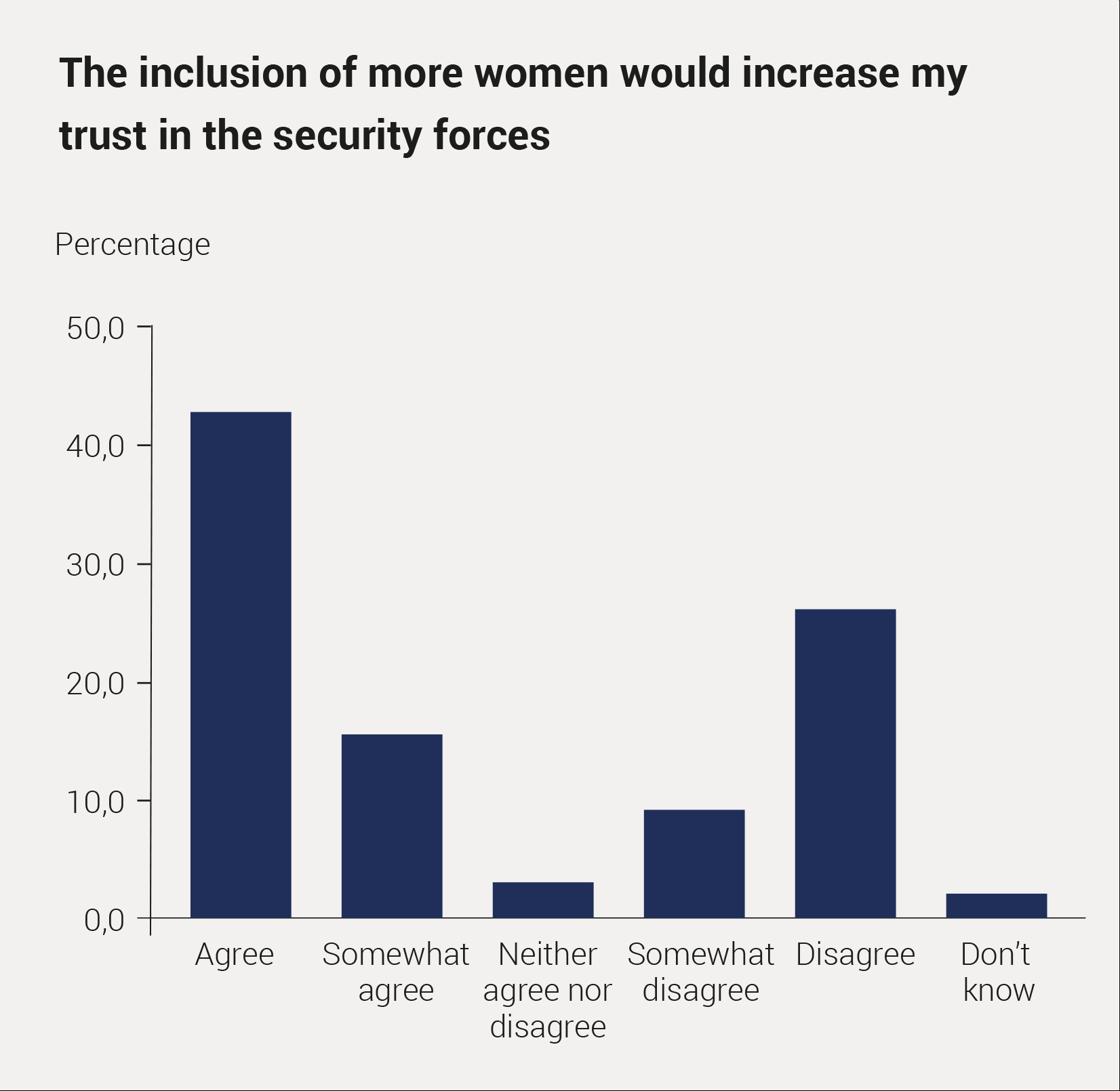

Another example of how social norms impact on the security of women is the substantial resistance to allowing women contact with the security forces to report problems. Women themselves are hesitant to report problems, but their willingness to do so increases significantly if the reporting can be made to a female officer. Currently, there are around three thousand female employees in the MoD, mostly in civilian capacities. The survey showed that a majority of both men and women agree that the inclusion of more women would increase their trust in the security forces.

However, the inclusion of women in the Iraqi security sector not only faces cultural obstacles but also practical ones, such as a lack of training facilities capable of accommodating both male and female recruits. Attention must also be paid to ensuring that women are not only trained but also supported in pursuing subsequent employment and given equal access to career promotion, including in areas directly linked to security provision. An effort should be made to incorporate the complementarity of experiences both among women and between men and women. Consequently, while the empowerment of women is important, real change depends on creating a shared understanding of how a diverse security sector that represents women and men of different ages and with varying experiences and perspectives will lead to a more comprehensive picture of the operational environment and consequently more effective stabilisation efforts.

Women, Peace and Security in NATO Mission Iraq

NMI is the first NATO mission to integrate gender perspectives into every stage of the initiating, concept development and planning processes. As a result, NMI’s WPS agenda has both an internal aspect that reflects NATO’s own understanding, implementation and adherence to the WPS agenda, and an external aspect that is more directly focused on assisting the Iraqi MoD in its implementation of UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions. Internally, NMI now has both WPS advisors and gender advisors, who work to gender-mainstream NMI activities. However, more can be done to clarify the WPS mandate and to strengthen the general understanding of how the WPS agenda contributes to overall operational effectiveness. Internally, WPS must be approached as both an inclusive and a cross-cutting agenda, and not a ‘women’s’ agenda.

The Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda was formally initiated by the landmark UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000), which was adopted on 31 October 2000. UNSCR 1325 affirms the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts and in peace-building initiatives.

Externally, NMI’s WPS advisors advise and assist the MoD in particular. Iraq was the first Middle Eastern country to adopt a National Action Plan (NAP) to implement UNSCR 1325 on WPS in 2014, and the second NAP for 2020-2024 was adopted in December 2020. However, whereas Iraq has made a formal effort to address the issue of the limited role of women in the security sector, anchoring in the Women's Empowerment Department (WED) in the Secretariat of the Council of Ministers and providing for its actioning by ministerial WEDs, implementation remains weak. Consequently, more work should focus on mainstreaming the NAP into wider national and sectoral policies and frameworks.

Learning from the Swedish experience

WPS is a top priority in Sweden’s foreign policy, as demonstrated by the development of a gender-responsive security-sector reform (SSR). Gender-responsive SSR is attentive to how existing gender norms in society can contribute to unequal access to and interaction with security institutions for men, women, boys and girls. In line with this, Sweden advocates a holistic SSR to avoid isolating the WPS agenda from broader reforms. It is also important that the different insecurities faced by men, women, boys and girls are addressed. Finally, the WPS approach should account for variations in the experiences of different women and existing hierarchies between women based on other identity factors, such as age, social class, ethnicity, religious background, marital status and other locally relevant identifiers.

Hence, whereas organisational backing is key to the implementation of WPS, delegation of the WPS to specific demarcated organisational entities risks side-lining the WPS agenda and creating a sense that it is a donor-driven agenda for giving women preferential treatment. This can lead to pushback against those involved in the WPS agenda. The Swedish experience shows that a rigid concentration on counting women can lead to strategies that focus on fulfilling quotas for women, potentially by assigning women responsibilities that are traditionally considered women’s issues. Such initiatives can be counterproductive in promoting gender equality, as they categorise men and women in accordance with existing stereotypical roles. At the same time, however, the inclusion of women must take into account cultural norms. Otherwise, included women will have little impact and potentially face discrimination, sexual harassment and abuse by the members of their communities.

‘Add women and stir’

The Swedish experience has shown that it is not enough to increase the number of women in the security sector (‘add women and stir’) if this effort is not accompanied by an equal focus on raising men’s and women’s awareness of the operational advantages and moral fairness of equal opportunities and diversity, in the security sector as much as with the public. Specifically, attention must be given to creating an inclusive work environment, both mentally and physically. This includes establishing functioning policies, codes of conduct and accountability mechanisms, providing gender-mainstreamed facilities and logistical support, and conducting surveys, workshops and other activities that promote an unbiased organisational culture of respect.

Finally, a key element in supporting the implementation of the WPS agenda is working with civil-society organisations. However, it can be difficult to identify relevant organisations. Hence, whereas women’s organisations represent valuable sources of information, they are often weak and can be further undermined if they become too strongly associated with international actors. Instead, these organisations must be supported in building relations with the broader community, including men, and in including non-elite women from across the country.

For this nationally representative survey, 1,606 interviews were conducted by the Independent Institute of Administration and Civil Society Studies (IIACSS), the only body representative of GALLUP in Iraq. The interviews were conducted proportionately across Iraq’s eighteen governorates and were gender- and age-balanced.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the survey was carried out by phone using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). Data collection was done in December 2020 and January 2021.

Please note: The title of this brief overlaps with a 2015 UN report on women’s inclusion and influence on peace negotiations edited by Thania Paffenholz et al.

DIIS Experts