DIIS Policy Brief

Immanent conflict without immanent war: Local actors and foreign powers are scrabbling for influence in Iraq and Syria

The direct, violent confrontations between the US and Iran are over for now, but conflicts in Iraq and Syria are far from resolved. The fragmented nature of the Iraqi and Syrian states and the presence of multiple militias backed by foreign actors mean that conflicts can easily escalate. The current turmoil and potential power vacuum may also provide fertile ground for the Islamic State (IS) to return.

Illustration © Pexels. Jens Mahnke. copyright license

RECOMMENDATIONS

■ Denmark should focus its attention on the border region between Iraq and Syria, which presents a high risk of insurgency, and is where the main Danish military contingency has been deployed since 2015. • Given the likely partial US withdrawal from Iraq, NATO and European governments should prepare for taking on new tasks and responsibilities.

• The US-led coalition should allow and prepare SDF to negotiate alternative political/security arrangements, as SDF may have difficulty sustaining its presence in Syria.

• The US-led coalition should allow and prepare SDF to negotiate alternative political/security arrangements, as SDF may have difficulty sustaining its presence in Syria.

Iraq: Caught between a rock and a hard place

Recent escalation between Iran and the US, has further accellerated political turmoil in Iraq and jeopardized the international campaign to defeat IS. Since October of 2019, thousands of ordinary, mostly young, Iraqis have continued protesting despite the resignation of Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi and a violent crackdown by security forces and militias. Beyond their scale and resilience, what makes these protests novel is their cross-sectarian call to change the corrupt, patronage system (Muhasasa) established after the US-led invasion in 2003, as well as their opposition to both Iranian and American influence.

At the core of Iranian influence are Shia militias such as the Badr Brigade forces, Kata´ib Hezbollah and Asa´ib Ahl al-Haq, which Tehran helps finance and train. These militias have existed in different constellations with Iranian backing since well before IS, but they were further mobilized in the wake of the IS invasion. The partial collapse of Iraq´s security forces and Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani´s fatwa calling Iraqi civilians to arms ensured a more important and popular role for the Shia militias in the fight against IS.

The militias gathered into the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), which became an umbrella term for the paramilitary forces battling IS. The various PMF outlets are affiliated with different parties and religious leaders and are overwhelmingly Shia. Former prime minister Haider al-Abadi enrolled the PMF into the regular armed forces as he recognized their importance in the fight against IS. This was also one element of a series of efforts to increase state control over the armed forces. Yet many militias remain closely affiliated with Iran and are supported by the Iranian Quds Force.

New escalation after the assassination of Suleimani

Meanwhile, US troops, who were expelled from Iraq in 2011, have been back in the country since 2014 when the Iraqi government invited an American-led international coalition to help fight IS. However, in the aftermath of the territorial defeat of IS, Iran has increasingly pushed for an expulsion of coalition troops from Iraq, both through diplomatic means and through attacks from Iran-affiliated militias. A series of rocket attacks attributed to Katai´b Hezbollah, killing an American contractor, have particularly catalysed the recent escalation. The American killing of the Iranian Quds force leader, Qasem Suleimani, and the PMF deputy chairman, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, has led to public anger in Iraq. In its aftermath, the Iraqi parliament and caretaker government have requested a withdrawal of coalition forces. A resolution which is not binding due to the caretaker governments temorary status. Meanwhile operations to counter IS have been partially suspended.

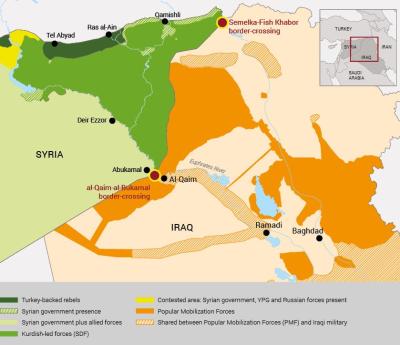

These transnational Shia groups move rather freely across the Syrian–Iraqi desert, and they are also manning the border crossing at Abukamal-al-Qaim

Even in the Sunni-dominated region of Western Iraq, where Denmark´s main military contingency has been deployed since 2015, Iran-affiliated PMF have a strategic presence and move freely back and forth between Syria and Iraq. Kata´ib Hezbollah and Liwa al-Tafuf mainly control trafficking and commerce in the border area, including the al-Qaim–al-Bukamal border crossing to Syria. The relationship between the Shia militias and the, overwhelmingly Sunni, local population is, however, marked by mistrust, despite a decrease in violence following the territorial defeat of IS. IS sleeper cells persist in the area and frequent attacks are still launched in the region and beyond. Recent escalation, political turmoil and the potential withdrawal of coalition forces increase the risk of violent confrontations in the region.

The broader security situation is influenced by strategic competition between multiple armed actors in the region, direct and indirect great power interference, including the Iranian-affiliated militias, and scattered tribal Sunni forces within the PMF. Moreover, the structural, political and economic problems, which laid the foundation for IS success, such as high unemployment, lack of infrastructure, and political marginalization, remain unresolved. Despite these circumstances large groups of young protesters continue to demand political and economic sovereignty and reform in Iraq´s major cities. These groups proclaim: ‘No to the US, no to Iran. Sunnis and Shias are all brothers’.

Syria’s north-east: a new scrabble for influence

The intensified US–Iran conflict will possibly also have stark implications for north and north-eastern Syria. Here, Iran-backed militias are operating relatively close to American forces and conflict may therefore escalate. If US troop presence is minimised in Iraq, this will put local allies and the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in an even more precarious situation.

A new complex battlefield of multiple militias backed by competing external powers was already emerging in Syria’s north-east in the autumn of 2019, after the Turkish incursion and the partial US withdrawal. Turkish-supported Arab militias – consisting of remnants of the Free Syrian Army, jihadist fighters and criminal gangs – entered the northern border region, while the Syrian regime forces moved to border posts along the Turkish frontier for the first time in seven years. Russian forces also began policing the border region and have taken over three former American bases.

The Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) is, however, still present in the north-east. The Syrian regime, pressed for resources and manpower, appears to be letting the YPG’s local governance and police institutions go largely untouched for now. Over the course of the Syrian war, Kurdish YPG has, in fact, loosely coordinated governance and security with Damascus. Yet for now the YPG seems to oppose Damascus’ calls for any enrolment into the Syrian army and is maintaining cooperation with the international coalition and the US in part of north-eastern Deir Ezzor.

In Deir Ezzor there is, similarly, a new scrabble for influence among the many Arab clans and extended families. Arab tribes have, from the beginning of the Syrian war, been divided between factions who joined rebels and later the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF); those who joined regime-loyal militias; and those who pledged their allegiance to Islamic State. With US influence waning, Iran, Turkey and Russia are all trying to reach out to tribal groups, potentially breaking up the SDF from within. Moreover, clans and bedouins have traditionally exercised a great deal of autonomy, with their own local ‘police’ and reconciliation mechanisms, but also with a vast network of smuggling routes across the border with Iraq. These are networks that the Islamic State – and before that al-Qaeda – have taken advantage of historically and which they may exploit again.

Increasing tension within Syrian Democratic Forces

While the US initially proclaimed in the autumn of 2019 that it would pull out entirely from Syria’s north-east, the US president seems to have settled for a US force of about 500 men in oil-rich Deir Ezzor. Officially, the US presence is intended to defeat the remnants of IS, but it is likely also a bid to balance Iranian influence in the border region. However, there are increasing tensions between the Kurdish and Arab factions within the SDF, and as the latter is traditionally based in Deir Ezzor, it may cause an eventual split of the Kurds from the SDF umbrella. If US forces are forced to withdraw from Iraq, they may also struggle to sustain their presence and protection of the SDF, as the control of the Semelka–Fish Khabur border crossing with Iraq is vital for stabilization and delivery of humanitarian aid.

In western Deir Ezzor and the villages along the River Euphrates and the Iraqi border, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and Iranian-supported Shia militias are especially dominant. Shia fighters come from as far afield as Pakistan and Afghanistan but are mainly drawn from the Iraqi PMF and Lebanese Hezbollah. These are not only fighting, but also building up local governance structures and religious institutions, and two new Iranian bases. These transnational Shia groups move rather freely across the Syrian–Iraqi desert, and they are also manning the border crossing at Abukamal-al-Qaim. From here weapon supplies and goods can travel from Iran, to and through Iraq to Syria and all the way to Lebanon.

Although IS has lost its last sliver of territory in Syria, it has already taken measures to organize as an underground terrorist and insurgent group. In recent months it has carried out hundreds of smaller attacks and assassinations in Syria. Some of its members have taken advantage of the new situation on the ground, while others have managed to reintegrate into tribal structures. With the current turmoil and potential for power vacuums in Syria and Iraq they may strengthen their positions even further.

Thus, despite the territorial defeat of IS, the Iraqi and Syrian state orders are fragmented, and multiple non-state militias backed by rival foreign powers remain. The two governments have little control over their territories, have difficulty providing basic state services, and continue to repress political dissent. Stability and safety have far from returned to the two war-torn countries.

DIIS Experts

Photo/illustration by Mads Nissen

Immanent conflict without immanent war

Local actors and foreign powers are scrabbling for influence in Iraq and Syria