Governing Outer Space – legal issues mounting at the final frontier

The commercialization and securitization of the space sector are challenging the regulatory regime of outer space. Rapid developments call for new and improved governance. The EU and Denmark should:

- insist on the development of law through the institutions of the international community, to avoid losing initiative to a few dominant actors.

- seek allies who also wish to find ways to share the common resource of orbital space and make sure that space remains open to all.

- support international efforts to limit space junk, light pollution and other environmental issues in space, acknowledging that orbital space is part of Earth´s environment and should be regulated as such.

In 2022, the private space firm SpaceX successfully launched 61 rockets, adding hundreds of satellites to its burgeoning, globe-spanning mega-constellation. SpaceX´s Starlink-project now comprises more than 3,000 satellites. For comparison, the European Space Agency launched six rockets in 2022 and operates less than 50 satellites in total.

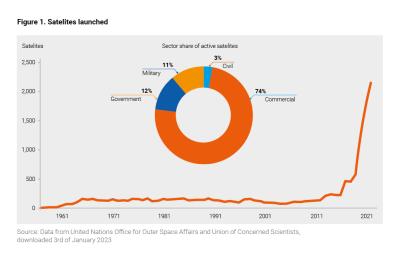

In the span of a few years, private space companies have dethroned nation states as the dominant actors in outer space. Today the vast majority of satellites are owned and controlled by commercial companies. During the first months of the Russian assault on Ukraine, several commercial space companies stepped in to provide vital satellite images and space-based Internet in support of the Ukrainian defense. This exemplifies the three currently dominant trends of human space activities: expansion, securitization and privatization.

The global space industry is undergoing the most fundamental and swift changes since the original space race ended when Neil Armstrong placed the first boot marks on the moon in 1969. The rapid changes raise a number of serious governance issues in areas such as national security, environmental protection and the rule of law in outer space. Denmark, Europe and the international community at large all have an acute interest in insisting on space being a global commons in which conduct can and should be regulated to benefit all of humanity – not just a few profit-seeking billionaire-owned space companies. Developments in the space industry are fast and accelerating. As with other global governance issues, like climate and cyber issues, achieving global accord on new regulations for space activities will be difficult and time-consuming, so prudent policymakers should get started right away.

The foundations of the International Law of Outer Space

The international regulation of Outer Space rests upon the five foundational treaties concluded in the first two decades after the start of the human space age which began with the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 in 1957. The first four of the five treaties enjoy broad international support and most spacefaring nations have signed them (see box). But the fifth treaty, the Moon Agreement of 1979, was never ratified by the leading space powers, and with this failure the early spurt of successful treaty-making in space governance ended.

The principles from the Cold war to today

The principles set out in the initial Outer Space Treaty half a century ago radiate a spirit of international cooperation and a belief in the common good that can seem almost naïvely optimistic in the current frosty geopolitical climate. The treaty benignly provides that; “exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries and shall be the province of all mankind, that outer space shall be free for exploration and use by all States and that all astronauts shall be regarded as the envoys of mankind.”

These original principles are challenged today by the fact that commercial and billionaire-owned space ventures have eclipsed public space programs. How does the principle of “for the benefit of all” apply to the profit-seeking commercial firms dominating space today? Is it still appropriate to bestow the status of “envoys of mankind” on astronauts if they are billionaires going to space solely for their own opulent entertainment?

The “Outer Space Treaty”, formally the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, 1967

- The ”Rescue Agreement”, formally the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space, 1968

- The ”Liability Convention”, formally the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, 1972

- The ”Registration Convention”, formally the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, 1975

- The ”Moon Agreement”, formally the Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, 1979

The first of the treaties, the Outer Space Treaty, set out fundamental legal principles governing activities in space, and can be considered a “Magna Carta” for space activities. The core principles contained in the Outer Space Treaty are generally accepted as international customary law and are therefore binding on all states.

To prevent a return to the time when dominant powers raced to colonize land, the treaty prohibits any national appropriation and claim of sovereignty in outer space. The prohibition on claiming land in space has again become relevant and contentious today as several countries and companies plan missions to the Moon and Mars. The United States, with the “Artemis Accords”, are pushing hard for a (re)-interpretation of the principles that allows for the establishment of exclusive “safety-zones” and the national and commercial extraction of natural resources on the Moon and other celestial bodies. The Accords have been criticized for being a thinly-veiled attempt at legitimizing corporate appropriation of territory in space and for undermining the efforts aimed at finding solutions through the UN institutions. However, as acceptance of the Artemis Accords is a prerequisite for participation in the prestigious NASA lunar program, many countries have already agreed to their terms. Denmark has not yet joined the Accords and must balance supporting international collaboration through UN institutions against supporting an important ally.

Other important contributions of the original treaty include the prohibition against placement of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction in space, the requirement that states be internationally responsible for public and private space activities, and the reaffirmation that international law, including the UN Charter, applies in space.

In sum, the general principles laid down in the Outer Space Treaty are fundamental to international space law, but they are showing their age. The space around our little blue planet is less empty than it used to be. The population of human-made space objects in orbit is skyrocketing, fundamentally changing the near-earth environment. The new pace of technological development and commercialization in the space sector requires the international society to get together and solve the new governance issues unfolding above the clouds.

The pressing issues of space governance exist in the cosmic coastline of Low Earth Orbit, not in the infinite cosmic ocean beyond.

Contested space

In discussions of practical space governance, the term “Outer Space” can be misleading, as it conjures images of faraway galaxies and exotic planets, whereas the vast majority of space activities plays out a few hundred kilometres above our heads. The pressing issues of space governance exist in the cosmic coastline of Low Earth Orbit, not in the infinite cosmic ocean beyond. Recent years have seen a ten-fold increase in the number of satellites launched. The result is ungoverned congestion and competition in vital orbits where national and commercial operators are vying for room and advantageous positions. Geopolitical tensions have caused a shift towards militarization in space. The United States recently established a new military branch, the Space Force, while NATO has designated outer space as a warfighting domain, and even the EU is increasingly turning its space funding towards security applications.

At the same time, the burgeoning commercial space sector is strategically utilizing the “dual-use” nature of space assets to serve both civilian and military customers. For example, the same Starlink satellites supplying military data to Ukrainian forces are streaming Netflix to teenagers in other parts of the world. While it is clear that general humanitarian law applies in space, there are many unanswered questions about how and when commercial space infrastructure can lawfully be targeted in an armed conflict.

Time for space environmentalism

Space junk left over from derelict spacecraft, rocket bodies and debris from anti-satellite tests are threatening the vital infrastructure supporting modern society and the life of astronauts working in space. Although the issue is still critical, the global space debris governance regime is maturing, with strengthening global norms and an emerging consensus for stricter technical standards and against deliberate debris creation, such as kinetic anti-satellite weapon tests.

Governance of active satellites is much less mature. The increasingly congested orbital highways around Earth have no common traffic rules and the risk of catastrophic collisions is rising. There are indications already that the increasing rate of satellites burning up in the atmosphere is having a significant negative impact on the ozone layer and the climate. At the same time, light pollution from new mega-constellations is uniting astronomers and indigenous peoples around the world, who are equally terrified at the prospect of having to view the night sky through a net of ever-moving satellites. We do not yet have enough data to fully understand how the massive expansion of the satellite population will affect Earth’s environment.

Although a nascent global awareness of space as an environment in need of regulatory protection is emerging, there is a need for nations to publicly support the agenda. The European Space Agency (ESA) is positioning itself as a global frontrunner in space sustainability, developing standards and technologies to limit space debris generation. However, national and international regulators must step in to provide the legal basis for ensuring a sustainable future for humanity’s space activities.

Taking a stand for the future of space governance

The outlook for a new, binding multilateral treaty solution for the governance issues of today is bleak. However, there are other paths to governance. The potential hazards resulting from the lack of clear governance of the rapidly-expanding commercial space sector are recognized by scientists, policymakers and NGOs worldwide. A host of initiatives, in the form of technical standards, norms, guidelines, best practices and similar non-binding instruments are being pushed forward to steer the development..

Compared to many of our peers, Denmark has been lethargic in the field of international space policy. On a positive note, there are now obvious steps Denmark can take to assume a more responsible stance in space governance, such as less parsimonious contributions to the ESA, active participation in the UN space forums and signing into new instruments clearly aligned with Danish interests such as the memorandum against anti-satellite weapons. As a small state reliant on the international rule of law, Denmark has every interest in more actively pursuing the development of a new and up-to-date space governance through the institutions of the international community.