Donald Trump and the battle of the two percent

US pressure on its NATO allies to increase defence spending is likely to continue, especially if Trump wins the US presidential election. Denmark can look to Germany to anticipate how pressure from the US will play itself out.

‘All NATO Nations must meet their 2% commitment, and that must ultimately go to 4%!’ - (President Trump, Twitter, 12 July 2018)

■ Denmark should carefully monitor defence spending in other European countries, particularly in Germany, to be able to anticipate increased US pressure on itself.

■ As an active contributor to international operations abroad, Denmark should continue to emphasize the efficiency of its defence spending as a factor of importance in NATO, but not expect it to be able to deflect US criticism fully, especially if Trump wins a second term.

■ Denmark should proactively seek to prioritize defence spending in areas where US and Danish national interests coincide the most, as they do in the Arctic.

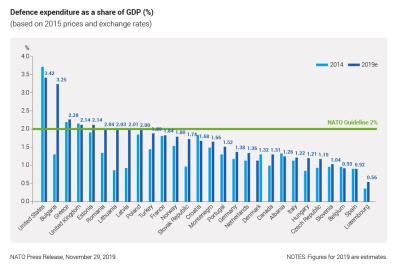

Donald Trump’s first term has been controversial, to say the least. The upcoming US elections in November, – including the question of whether or not Trump might win a second term, brings into focus the question of whether and, if so, how much the Trump presidency might be diverging from the last few previous US presidents across a wide array of policy areas. That includes the future of transatlantic relations and of NATO. Indeed, NATO has been a favourite target of Trump’s criticisms, and Trump has repeatedly accused the non-US members of the alliance of freeriding on the US. As proof of this, Trump has fixated upon the failure of the majority of the alliance’s European members, as well as Canada, to meet the NATO spending target of devoting 2% of GDP to defence.

Trump’s approach has been characterized by considerable volatility. The NATO summit of July 2018 was marked by Trump denouncing his NATO allies as delinquent and suggesting that they should actually be paying not 2% of GDP, but 4%. In contrast, Trump was much more positively inclined towards NATO at the NATO summit in December 2019, at which he attacked French President Macron for his statements about NATO becoming brain dead. Nevertheless, Trump’s periodic return to the issue of NATO and what he sees as the lack of solidarity and freeriding of the other members underscores its continued importance as a key point of contention between the US and most of its NATO allies. This is especially the case given that, while Trump’s position on NATO may be extreme, American discontent with European and Canadian defence spending predates the Trump presidency by a long way.

What motivates the 2% agenda?

For as long as NATO has existed, the US has spent a higher proportion of GDP on defence than its allies and has routinely tried to push the latter towards greater burden-sharing regarding defence spending. Furthermore, the pledge all NATO countries made to strive towards spending a minimum of 2% of their GDP on defence in 2024 was formulated during the Obama presidency at the NATO summit in Wales in 2014. Therefore, American pressure on Europe and Canada to do more in defence spending is likely to persist even if Trump fails to win a second term.

American pressure on Europe and Canada to do more in defence spending is likely to persist even if Trump fails to win a second term.

What sets the Trump approach to NATO apart from previous administrations, however, lies both in its confrontational public rhetoric and in Trump’s willingness to disregard potentially negative outcomes stemming from such a confrontational approach. Thus, according to a growing literature on the Trump presidency, former top aides to the President – in particular a figure such as former Secretary of Defense James Mattis – have often had to dissuade the President from adopting too confrontational a line towards America’s NATO allies.

Hence, according to award-winning presidential chronicler Bob Woodward’s book Fear, Trump at one point stated that if Mattis wanted him to follow his advice on NATO, then Mattis would have to become ‘rent collector’. And in his most recent book Rage, Woodward directly ties Mattis’ decision to leave as Secretary of Defense in 2018 to his failure to move Trump on how to handle US relations with its allies in Syria (a combination of NATO allies and non-NATO allies) concerning the unilateral US withdrawal of troops from Syria. This focus on ‘rent’ as well as the willingness to walk away from allies when they are no longer deemed useful underlines both the transactional element in Trump’s foreign policy thinking and his fundamental belief that America is being cheated by its allies and therefore might be better off without them.

At the NATO summit in Wales in 2014, the gathered NATO Heads of State and Government agreed to aim for spending 2% of GDP on defense by 2024. This spending target has been criticized for failing to give a meaningful picture of actual defense capability, for failing to take into account non-military contributions to security and for failing to take into account other alliance contributions such as for example willingness to use military forces in the field. Proponents, however, stress that, whatever its flaws, the 2% target, along with the target of spending 20% of that budget on equipment, is the primary burden sharing measure that it has proven politically possible to agree upon in NATO.

It’s all about Germany

‘More allies are now meeting their commitments, but too many others are falling short, and as we all acknowledge, Germany is chief among them.’ (Vice President Mike Pence to a group of NATO officials, May 2019, Source: Politico)

Ever since the NATO decision at the Wales summit of 2014 to commit to meeting the 2% spending target by 2024, NATO defence spending has gone up. Indeed, the list of countries now meeting the 2% target includes all the Baltic countries, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Poland, the UK and the US. Key among those countries that are not yet meeting the 2% target, however, is Germany, the largest European economy and the second largest economy in NATO. Indeed, US-German relations have been troubled ever since President Trump took office, with the President recently calling Germany ’delinquent’ for spending too little on defence. In July 2020, this led the Trump administration to announce the decision to pull 11,900 of roughly 36,000 US troops out of Germany, some of them being redeployed to Poland, a country which, notably, meets NATO’s 2% spending target (the remaining troops will go elsewhere in Europe or back to the US).

This decision was taken in spite of grave concerns for the consequences for US security, expressed by both the American security apparatus and a bipartisan group of senators, including national security heavyweight Lindsey Graham. Of special concern for these groups is the potentially dangerous signal that this troop reduction sends to both Russia and America’s NATO allies about the US commitment to NATO and European security. Added to this is the fact that Germany is not only strategically located in the heart of Europe, but currently hosts some of the largest and most logistically important US military bases in Europe. Trump’s willingness to forego such considerations, in spite of advice to the contrary, shows Trump’s willingness to take risks and to accept costs to US security interests in pursuit of his fixation with the 2% target.

Though rhetorically extreme, Trump’s gamble is not without historical its precedents. The fight over NATO defence spending has often come down to German defence spending. This is not only because Germany is the largest European economy in NATO and therefore has the greatest potential actually to change the ‘balance of payments’ across the Atlantic, but also because of Germany’s symbolic significance. Thus, if the Germans begin to spend more, it is likely to make it harder for the other European NATO members and Canada to resist American pressure. Several factors indicate, however, that Germany may be moving on the matter, albeit slowly. Thus, Germany increased its defence spending by 10% in 2019, and in the same year Chancellor Angela Merkel promised to meet the 2% target – not in 2024, however, but in 2031. Similarly, the Germans recently announced an ambition to deliver 10% of NATO capabilities by 2031. However, the Germans have been quick to assert that these plans are tied to German national interests and have nothing to do with any pressure from the US.

If the Germans begin to spend more, it is likely to make it harder for the other European NATO members and Canada to resist American pressure.

Nonetheless, if Trump is re-elected, US pressure on Germany is likely to continue to grow. Should former Vice President Joe Biden assume the presidency, the pressure on Germany is likely to be less severe, since Biden, a long-term advocate of the transatlantic bond, is unlikely to be as willing to take risks as Trump or to sacrifice US operational capabilities by scaling down the US presence in Germany. Furthermore, Biden has repeatedly declared his intention of rebuilding America’s alliances. However, even a Biden Presidency is likely to try and keep the Germans to the 2% spending target, given that the Obama administration in which he was Vice-President was, after all, a main driving force behind it.

What this means for Denmark

The extent to which Germany complies with the 2% target, for whatever reason, is likely to put pressure on the defence spending of all NATO members that are falling short of it, especially on wealthy nations that spend less than Germany. This includes Denmark. Pressure from the US on Denmark in the matter of defence spending is a familiar problem in Copenhagen. The Danish answer has typically been that, despite the relatively modest level of Danish defence spending, Denmark manages to use this money in a very effective manner that provides maximum value for the NATO alliance as a whole and for the US in particular. For the last thirty years, that has included contributing substantially to international military interventions across the globe. The increased US focus on the Arctic means that US expectations in this region relating to the whole Kingdom of Denmark (Denmark, Greenland and the Faroes Islands) are also increasing. The recent Danish pledge at the NATO Summit in London in December 2019 to spend 1.5 billion Danish crowns extra in the Arctic indicates that this is well understood by the Danish authorities. If Biden wins the election in November, there is reason to be optimistic about such a strategy. Should Trump secure another term, however, his fixation with defence spending makes the strategy unstable at best. The Danish authorities therefore have every reason to follow the US–German disagreement over defence spending very closely as they unfold.

DIIS Experts