Development aid is unlikely to reduce migration from Africa

- Irregular migration from Africa is relatively stable though fluctuations occur. Many young Africans aspire to migrate, yet few realise their plans and, if they do, many migrate to other African countries.

- Research on migration patterns is moving away from economic determinism. Migration is only well understood when all internal and external drivers are considered.

- General development aid is unlikely to achieve a reduction in migration from Africa in the short or the medium term. To be successful it should be carefully designed to address the concerns of potential migrants locally.

Recent peaks in irregular arrivals from North Africa to Europe have led to oversimplified assumptions about the scale and role of conflict and poverty in migration. In fact, irregular migration to Europe is limited and a result of economic progress, making foreign aid an ineffective instrument to curb it.

It’s easy to get the impression from the mainstream media’s coverage of migration that a large exodos is about to take place from the African continent towards Europe, and that only drastic and sometimes draconian measures can stop this development. Yet, even if tragic and deadly, numbers show that irregular migration across the Mediterranean from Africa is relatively small and stable, though fluctuations take place from year to year.

Moreover, migration is not a result of a lack of development in Africa but part of a broader development process that increases both people’s aspirations and their capabilities to move. It therefore remains unlikely that more development aid will reduce migration in the short or medium term.

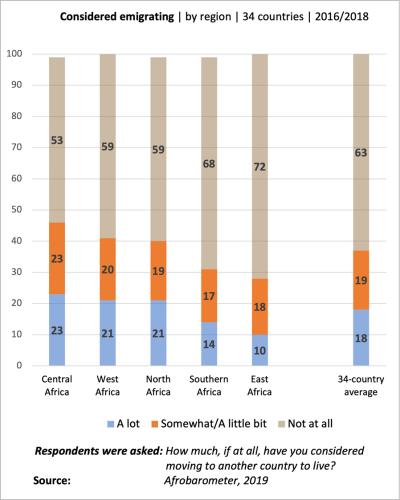

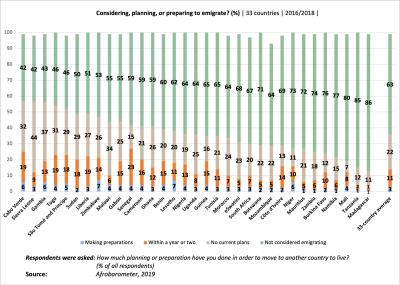

Many young Africans express a desire to migrate when asked. A 2019 Afrobarometer survey from 34 African countries compiling data from 45,823 participants showed that more than one in three had considered emigration, mainly to find work but also to escape hardships and poverty. Yet only one in ten of those potential emigrants had taken steps to realise their plans.

Young adults and highly educated citizens were most likely to express desire for migration. The reason why so few Africans are migrating when so many say they would like to is because the desire to migrate is better viewed as a proxy for life dissatisfaction rather than the actual plan or potential for migration, as one 2018 European commission report also concludes.

Stopping African migration with development aid

Given the growing political significance of migration in recent years, Europe has, especially since the 2015 so-called refugee crisis, sought to reduce migration through development aid. For this purpose, the EU has established a five billion Euros ‘Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa’ (EUTF).

This fund is an example of how development cooperation is increasingly fused with other agendas, such as trade, foreign policy and security. Over the past five years, the EUFT has funded 254 migration and displacement related programmes in 26 African countries.

Migration is not a result of a lack of development in Africa but part of a broader development process that increases both people’s aspirations and their capabilities to move.

A recent Oxfam analysis shows that more than a quarter of the projects between 2015 and 2019 were concerned with migration management, underlining how development aid is increasingly funnelled into security. For example, in Libya the EUFT funds the coast guard, while in Niger it funds border patrol enforcement in the Agadez region.

Another concern is that development aid is increasingly leveraged to pressurise African countries to adopt stricter migration policies and speed up readmission of rejected asylum-seekers. While this may forward the EU’s agenda on migration, it does little to achieve development or foreign policy objectives. In fact, this lack of policy coherence may undermine these objectives.

Moreover, many of the development aid projects take a point of departure in crisis narratives, European domestic policies and top-down understandings of the ‘root causes’ of migration. They are rarely developed in response to an understanding of the concerns of potential migrants, nor in collaboration with partners in low-income countries. This, again, does not bode well for long-term sustainable development.

What impact does aid have on migration?

To ask what impact development aid may have on migration, if any, we must first ask what motivates people to migrate from Africa to begin with. People moving towards Europe from Africa are a mixed group of people consisting of both refugees fleeing conflicts and migrants seeking better opportunities in life. It’s the latter group that we focus on here.

Another concern is that development aid is increasingly leveraged to pressurise African countries to adopt stricter migration policies and speed up readmission of rejected asylum-seekers.

Moving away from economic rationality as the dominant variable in migration, recent research uses the term ‘drivers’ instead of ‘root causes’ in order to enable a more complex understanding of the often mixed and multiple dynamics that shape migration. New theories thus foreground the important role of subjective aspirations and desires and how migration is not only shaped by local or regional dynamics but also by large scale global processes including unequal access to mobility.

Recent research led by Nicholas van Hear, for instance, suggests a ‘push-pull plus’ model to understanding migration and the ongoing desire for mobility. This model includes a macro perspective on structural inequality between destination countries and countries of origin as well as country-level socio-economic and political realities on the ground.

It also includes drivers that trigger actual migration such as sudden critical events that lead to individual or collective decision-making. And finally, this model acknowledges drivers that mediate migration, either by directly facilitating and consolidating migration or by cracking down on it. This way, migration research has moved away from dominant understandings of economic rationality in migration theories and sought to integrate multiple dimensions of the internal and external forces that give shape and content to mobility patterns in the 21st century.

Development aid unlikely to create growth and stop migration

Using development aid as a migration governance tool is not a new phenomenon. Yet, development tends to increase both internal and international migration. It is therefore not the poorest countries that produce large migration flows nor is it the poorest segments of the population that can mobilise the resources needed to travel internationally.

Migration demands both social, cultural and economic resources to connect to other people who can help facilitate the knowledge and resources needed to initiate and pay for the journey and settlement upon arrival. In short, in low-income countries, development and improvement in income levels, infrastructure and education will typically lead to more internal and international migration because people are more capable of realising migration plans and increasingly aspire to migrate.

Migration, in this connection, is ‘a vital resource’ rather than a sign of a desperate response to poverty, as Hein de Haas has argued. Moreover, evidence suggests that greater youth employment may deter migration in the short term if a country generally stays poor, but that it is unlikely to reduce migration when the economy grows and diversifies.

For low-income countries today, it will take several decades before they reach past middle income where migration rates are expected to slow down and reverse (approximately 8,000-10,000 US dollars in annual income per capita), and migration from middle-income countries is typically much higher than that from poor countries. Yet, at the point where low-income countries transition and become middle-income countries, out-migration from thereon reaches a plateau and starts to decrease. This inverted-U relation is often referred to as the migration hump or the migration or mobility transition model.

Could development aid push low-income countries above the threshold where would-be migrants decide to stay at home? Research shows that development aid is too small in scale and not designed to stimulate such significant economic growth. Its potential is rather to provide conditions for investments, increased productivity, trade and entrepreneurship by supporting health, education, infrastructure, governance and framework conditions for the private sector and the like.

Development cooperation cannot create millions of meaningful jobs with career prospects tomorrow or within a medium-term horizon, but potential migrants may be influenced by other concerns which carefully organised development support can address.

So far, little research has been able to establish a connection between specific aid-supported activities and the decision by potential migrants not to move. One study indicates that aid to social services that benefit potential migrants is likely to reduce emigration compared to aid to productive sectors that may actually provide the needed income to travel.

In line with the ‘push-pull plus’ model, it’s possible to speculate that safety-net and cash-transfer programmes that can significantly mitigate sudden critical events and family tragedies will reduce the realisation of migration plans. However, market opportunities and socio-political change of embedded intergenerational and other inequalities are needed, too.

Aid should, accordingly, address both context-specific conditions that vary from region to region in a country, and broader national political and economic matters. Such a comprehensive approach to addressing the concerns of potential migrants remains to be seen within international development cooperation.

This DIIS Policy Brief has received financial support from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. It reflects the views of the authors alone.

DIIS Experts