The dangers of the single story in the Fulani "Menace" narrative

Ghanaian media have been dominated by single-sided stories about the conflict between Fulani herdsmen and local farmers in the north. As most Ghanaians, Dr Deborah Atobrah, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, was influenced by these stories as she went to interview Fulani herdsmen as a member of the research programme Domestic Security Implications of Peacekeeping in Ghana (D-SIP). In this blog post, Dr Atobrah reflects on the importance of hearing both sides of a story, and what it means to do ethnographic fieldwork in one’s own country.

Like many other well-meaning Ghanaians, I had been drenched in negative sentiments about Fulani herdsmen before joining the Domestic Security Implications of Peacekeeping in Ghana (D-SIP) research group. Popular Ghanaian media representations of Fulani herdsmen as a bunch of ruthless, violent, and berserk men has stayed with me. Imagine being persistently bombarded with headlines such as ‘Fulani herdsmen more dangerous than Boko Haram – DCE (District Chief Executive ed.) fears’; ‘Forest guards abandon duty post to seek cover from armed Fulani herdsmen’; ‘Hunted Fulani murderer arrested after slashing throat of boy, 18’.

It is no wonder that such narratives evoke both national and community protests and responses, some of which have been captioned in the media: ‘Sekyere Central DISEC chases out Fulani herders’; ‘Fulani canker: MP joins Agogo youth to protest against Fulani herdsmen’; ‘Fulani Crisis: Regional Best Farmer weeps at loss; arms wife with pump action gun’; ‘Fulani: police, military begin one month operation to flush out nomads’. There seemed to be a public consensus that Fulani herdsmen were a ‘menace’, which needed urgent government intervention. As one media headline reads: ‘Fulani Herdsman to be kicked out in Operation Cowleg’ (Operation Cowleg is a joint police-military operation established to deal with herder-farmer conflicts ed.).

The dominant narrative had been that Fulani herdsmen allow their cattle to destroy farms and refuse to compensate farmers, which results in conflicts that can escalate into physical and violent clashes between farmers and herders

Such was the power of the dominant narrative that I was concerned when the D-SIP project team at the University of Ghana planned to interview Fulani herdsmen during our initial fieldwork trip up north. ‘At best, they would refuse to talk to us out of suspicion’, I thought to myself. I had clearly been influenced by ‘the single story’ circulated in the media.

As we drove from Accra through the five study sites of D-SIP in the Northern, Brong Ahafo and Eastern Regions of Ghana, I knew I had an opportunity as a researcher to exemplify concepts of objectivity, reflexivity and positionality in my data collection on the Fulani, and to enhance our study’s validity and reliability through triangulation. And so, when we handed over the imaginary microphone to them, to hear the narrative from their perspective, I found the herders’ sentiments of exploitation and exclusion profound and striking.

The dominant narrative had been that Fulani herdsmen allow their cattle to destroy farms and they refuse to compensate farmers, which results in conflicts that escalate into physical and violent clashes between farmers and herders. The narrative represented herders as notoriously recalcitrant, refusing to compensate farmers for the destruction caused by their cattle. To add insult to injury, they additionally violated farmers, women, and children in the communities. They kill, rape, rob, destroy, and move, as one narrative said.

The other side of the story

When we met a group of Fulani men in Gushiegu, we were struck by the fact that they were organized and identifiable and had systems in place for compensating farmers for the destruction caused by their cattle. Settlements were reached after assessments of the destruction had been made by a committee of traditional leaders, Fulani leaders, the farmer, and the herder. A leader of the Fulani association in Gushiegu explained that the value of the crops destroyed is determined by the farmer, which could be negotiated if it is found to be overestimated. The Fulani leadership asserted that in all cases of complaints brought to their attention, the herder duly compensates the farmer. I then thought to myself, ‘this sounds great! Communities should then be at peace with the herders. There’s no big deal here’.

However, we also discovered from the interviews that the Fulani believed that some farmers would deliberately leave a few crops on the farm after harvesting. As soon as the cattle get on their farms, the farmers would surcharge the herder with the value of the produce of the entire farm. Oftentimes, to avoid tension between them and the farmers, the herdsmen would settle huge bills they knew were unjustified. Herders felt the police and community leaders were often biased in their adjudication, favouring farmers because of the notion that the farmers are the indigenes and the herders are foreigners.

The interviews enabled us to hear the voices of spokespersons for the Fulani herder community demanding fair treatment and accordance of rights for the herdsmen. This complicated the single story we had come with, which like other single stories was distilled and unidimensional

In Donkorkrom, where there have been prolonged conflicts between herders and farmers, our interviewees disclosed that concerns about exaggerated claims had been addressed by the involvement of Agricultural Extension Officers in conflict resolution committees, which valued damage caused by cattle for compensation to moderate the process. Those interviewed recounted a popular case of a farmer who insisted on being compensated about twice what the committee had recommended. The case was reported to the police, who also thought her claims were overpriced and tried unsuccessfully to persuade her to accept the proposed compensation. When the case went to court and the necessary damage assessments were made, she was awarded a much lower compensation than she had originally been offered by the herder.

The Fulani herders also indicated that they never get justice when their cattle are killed and stolen by robbers and farmers, or when herders, mostly young boys, are attacked and sometimes killed by community members. Our respondents, the Fulani herders and their wives, argued that these and other examples made them feel exploited by farmers, who they believed were unhappy about their relative prosperity as herders. These perspectives of herders are missing from the dominant narratives on Fulani herdsmen in the Ghanaian media.

The interviews enabled us to hear the voices of spokespersons for the Fulani herder community demanding fair treatment and accordance of rights for the herdsmen. This complicated the single story we had come with, which like other single stories was distilled and unidimensional.

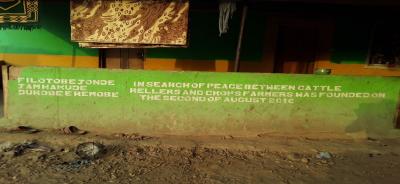

In this case, the single story represents Fulani herdsmen as a homogenous group of nomad herders, who are anonymous, untraceable and with no affinity for farming communities and their members. And yet, the sedentary Fulani had associations in most of the communities we studied, with leaders who mediated conflicts with members of other communities in “search for peace”, as reflected in the inscription on the photo captured below. The Fulani communities enter business partnerships with the so-called indigenes. A participant in our first focus group discussion among Nanumba men in Bimbilla owned about three thousand cattle that were being herded by a Fulani herdsman. While there were Fulani nomads, who were usually itinerant, there were also many Fulani settlers, some of whom had lived in the communities for over three generations. It may be specious to identify such settlers as people with no affinity for their communities. Why then would they be attending the funerals and wedding ceremonies of their Ewe friends in Donkorkrom?

Giving them the imaginary microphone to also tell their story demonstrated that, as in many other similar cases, there are two sides to every story, and therein lies the truth.

Deborah Atobrah holds a PhD and an MPhil in African Studies from the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana, from 2010 and 2003 respectively. She has two Post Graduate Certificates from the University of Bergen Norway, in Global Health Challenges (2010) and in Global Poverty and Development (2008).

Read more about the project: D-SIP – Domestic Security Implications of UN Peacekeeping in Ghana