Our climate future depends on conflict dynamics in Congo

- Illegal exploitation in the Congo Basin’s protected areas is a threat to the climate.

- State agents responsible for environmental protection often behave like armed groups, facilitating illegal access to resources.

- Deforestation and conflict over resources in the Congo Basin only increase in scale when they involve competition between elite power networks.

- Conservation efforts can exacerbate conflict through increased deployment of enforcement agencies.

The Congo Basin rainforest – the second largest on earth – absorbs four percent of global CO2 emissions and constitutes a crucial line of defense against cataclysmic climate change. However, a complex mix of illegal resource exploitation and conflict is currently threatening the rainforest. To curb these threats and their global consequenses, we need to understand the interplay between resources, conflict and environmental protection in Congo.

The Congo Basin rainforest is one of the most biodiverse areas in the world and home to iconic endemic species such as the okapi and the bonobo. Owing to the rapidly unfolding climate emergency, this rainforest has become of ever greater global significance. Aggressive deforestation in Brazil means the Amazon rainforest has officially reached the tipping point, moving from a ‘carbon sink’ — a vacuum cleaner absorbing CO2 from the air — into a source of carbon emissions. Consequently, the Congo Basin rainforest is now the only remaining net carbon sink in the world. Moreover, scientists recently discovered vast peatlands in the portion of the Congo Basin rainforest located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). These peatlands store such a big and dense concentration of carbon that deforestation would release enough carbon to make catastrophic climate change unavoidable.

Over half of the Congo Basin rainforest lies in the DRC. Therefore, local environmental protection there has suddenly become of global importance. Yet the DRC’s protected areas, which cover an important part of the Congo Basin forest, are caught up in a complex mix of armed conflict and illegal resource exploitation. While the forest remains largely intact, small-scale loggers, poachers and miners are making inroads into protected areas. Often resource exploitation entails deforestation and biodiversity loss, which in turn weaken the crucial carbon uptake and storage functions that the forest fulfills for the world. The Congolese government only dedicates minimal resources to environmental protection and its agents are often complicit in illegal resource exploitation. The presence of armed groups, motivated by local grievances and attracted by resources and the refuge that reserves can offer, further complicates the situation.

New research in the DRC identifies three key mechanisms through which contestations around illegal resource exploitation interact with armed conflict and conservation efforts.

The DRC’s protected areas, which cover an important part of the Congo Basin forest, are caught up in a complex mix of armed conflict and illegal resource exploitation.

1. Bolstering armed groups

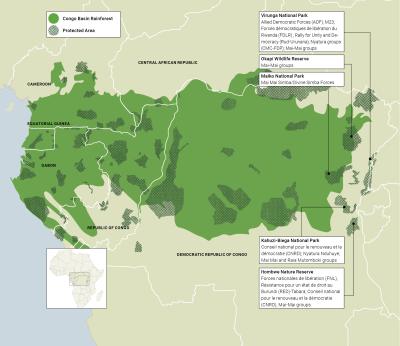

Most protected areas in eastern DRC are home to a range of armed groups (see map). These groups benefit not only from the shelter offered by the remoteness and sparsity of road infrastructure in protected areas, but also from the abundance of natural resources. Armed groups can gain revenue from illegal resource exploitation in protected areas in several ways. In zones under their control, they seek to monopolise access to resources. This allows them to organise and establish various degrees of control over the commodity chain (including production and trade) or to extract protection fees from civilians engaged in resource exploitation. In addition, they often ‘tax’ the circulation of resources by means of erecting roadblocks.

Enabling exploitation by civilians fosters popular support for the presence of armed groups. It makes people reluctant to collaborate with the state security services, because many civilians depend on illegal resource exploitation for their livelihoods. If armed groups are too weak or mobile to control illegal activities, they may still benefit from them through hit-and-run tactics. In the Okapi Reserve, various armed groups have sustained themselves through periodical raids on illegal mining sites, extracting taxes and supplies from miners and forcibly recruiting them as porters, before retreating into the forest. The Lord’s Resistance Army in Garamba Park, in turn, was occasionally involved in poaching ivory.

2. Sparking elite competition

Armed groups are commonly part of larger networks that involve politicians and businesspeople who also benefit from resource exploitation, for instance, by organising trade or pre-financing exploitation. Members of state security services, including the Congolese army (FARDC) and the Congolese Agency for Nature Conservation (ICCN) may also be involved in illegal resource exploitation, according to our recent research. These state agents are equally embedded in broader networks that have a stake in this illegal economy.

These diverse networks, which cross state/non-state and civil/military boundaries, are often in competition. This competition can turn violent when changes occur to the existing distribution of wealth and influence. For instance, in the Okapi Reserve, there is a growing number of illegal gold mining operations run by Chinese companies, which are protected by army units. The latter have – often violently – displaced thousands of artisanal miners who benefited from the protection of and made payments to competing politico-military networks. Losing access to their livelihoods, a part of the dislodged miners and their networks are supporting armed groups and bandits who violently target the Chinese mining operations. In Kahuzi-Biega National Park, several armed groups have fought over the control of gold mining sites in the park’s highland sector, leading to the deaths of three high-profile rebel chiefs since 2019.

3. Conservation fuels conflict

It is often assumed that illegal resource extraction is symptomatic of an absence of governance. However, in many protected areas in eastern DRC, there is a considerable presence of state agencies responsible for security and conservation law enforcement. Yet many of these agencies are themselves involved in illegal resource exploitation, including by allowing such exploitation to happen in exchange for ‘protection fees’ and taxes. This reinforces illicit exploitation also indirectly, by providing it with a veneer of legality. One example is artisanal gold mining in the Okapi Reserve, which is tolerated and taxed by a range of state agents, ranging from national and provincial tax authorities, to the forest and mining administration, to the security services. In Garamba Park, security forces deployed to curb poaching and hunt the LRA have themselves been involved in poaching and the ivory trade.

Aside from intensifying illegal exploitation, the presence and involvement of enforcement agencies can fuel armed conflict in three ways. First, it can spark the type of violent competition described above. Second, enforcement agencies can strengthen non-state armed groups through informal collaboration. For instance, because of the support of an influential Congolese army commander, a group of poachers in the Okapi Reserve grew in size and boldness, developing into a fully fledged militia that wreaked havoc in the reserve, attacking its headquarters. Third, enforcement activities can create grievances, including through human rights violations and by undermining people’s livelihoods and access to land, which lead people to take up arms or intensify their support for armed groups.

Engaging the resource-conflict nexus

Contrary to what is commonly assumed, conflict dynamics in the eastern Congo Basin are not driven by human-induced climate change and have nothing to do with resource scarcity. Nor can we ascribe illegal resource exploitation in protected areas to the absence of the state. Instead, public authorities use their positions to profit from illegal resource extraction rather than curb it. These authorities are part of competing networks of power that cut across business, political and military elites, and that involve rebels and state agents on the local level. It is the violent competition between these networks that drives both armed conflict and illegal resource exploitation.

To curb this competition, political and governance reforms are needed, particularly in the DRC, that stretch far beyond protected areas. To start with, it is crucial to reform the army in order to reduce its direct and indirect engagement in damaging forms of illegal resources exploitation. Furthermore, law enforcement efforts should not uniquely focus on those exploiting resources on the ground, who are often poor civilians and lower-level state agents. Rather, they should hold the broader political-military networks these people are part of accountable. Finally, it is crucial when thinking about reforms to protect people’s livelihoods. Enforcement activities that undermine people’s basic income without offering a viable alternative will feed negatively into conflict dynamics.

This policy brief is the result of research conducted with funding from the United States Institute of Peace. For a more detailed discussion, see the 2022 USIP report ‘Armed Actors and Environmental Peacebuilding: Lessons from Eastern DRC.

DIIS Eksperter