Managing US-China Rivalry in the Arctic

Many fear that strategic competition between the US and China threatens longstanding regional cooperation and stability in the Arctic. But if they recognise their own political and economic significance and work collectively, the Nordic states and Canada can still play an instrumental role in steering the region’s future away from confrontation.

- Recognise how US–China strategic competition represents a false binary for policy choices in the Arctic.

- Understand how economic connectivity provides room for manoeuvre against big power pressure.

- Encourage participation of non-Arctic states with similar economic and political norms on natural resource and infrastructure development.

China emerges, America responds

New geopolitical tensions between the United States and China in the Arctic are another sign that the exceptionalism of low security tension that the region has long enjoyed is now in jeopardy. Alongside Russia’s military buildup and China’s growing strategic interests, the American return demands that policymakers in Nordic states and Canada pay renewed attention to crafting foreign, economic and defence policy in the region. Washington’s moves in recent years to halt Chinese engagement in Greenland’s critical infrastructure, and its campaign cautioning regional capitals from working with Chinese telecommunications company Huawei in their 5G mobile networks, are both part of what some see as a new Cold War brewing between the United States and China.

China has attempted to push in the other direction. It has shown increasing preparedness to employ coercive diplomacy in attempts to shape the decision-making of Arctic states and autonomous territories such as the Faroe Islands. Beijing has used trade relationships as leverage to advance foreign policy aims against Norway and Canada in a growing number of disputes within the region that are byproducts of US–China competition, but also the result of Beijing’s new assertiveness in defending its political values abroad.

Nuancing American and Chinese Arctic policy

There are different opinions on what America’s return to the Arctic and confrontation with China means for regional security. American Arctic experts worry that Washington’s new Arctic diplomacy and security policy is still largely rhetorical and underwhelming at advancing American Arctic capabilities, particularly if Russia and China pursue closer strategic and military cooperation in the future. In the Nordic states, Arctic researchers and commentators see the May 2019 speech of US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at the Arctic Council meeting in Finland as a divisive turning point away from regional cooperation. Pompeo upset diplomatic sensitivities when he called the Arctic an ‘arena for power and for competition’ with China and Russia. Some view the new American defence strategy, assertive diplomacy and military exercises in the Arctic as destabilising and provocative towards Russia and China.

The Trump administration’s discourse on great power competition in the Arctic can be harsh, obtuse, and self-defeating at times. Overreaction to China should be avoided and a decoupling agenda does not represent a viable path forward. Many of China’s Arctic engagements do, after all, have scientific and commercial aims that dovetail with the interests of Arctic states and autonomous territories. These range from understanding the effects of climate change to exploiting new shipping routes, developing infrastructure, and extracting energy, minerals and rare earths.

But, just as for China, some nuancing of US discourse, policy and actions in the Arctic is also called for. Washington’s newly appointed Arctic coordinator, Jim DeHart, advances a more cooperative tone and a commitment to maintaining low security tensions. This is an approach Democratic nominee Joe Biden will likely maintain should he win the upcoming US presidential elections. In fact, the US is not moving to block all Chinese engagements in the Arctic. For example, China is a significant destination for Greenlandic fish exports and an investment partner in mining interests on the island. Moreover, the United States is not the only Arctic state voicing concerns over some Chinese activities. In 2019 Danish and Swedish defence intelligence services warned of potential ‘dual use’ civilian–military capabilities in Chinese research and technology.

False binaries in Arctic relations

Despite the importance of great power competition, Arctic policymakers, researchers, and journalists should take a cue from their counterparts studying US–China relations in the Indo-Pacific and avoid an excessive focus on the strategic rivalry. This can act as a psychological trap by presenting, as former Singaporean diplomat Bilahari Kausikan argues, a simplistic, false binary for policy choice. The United States and China are by far the two largest economies in the world, and command the two strongest militaries, but they are still only part of a multipolar global order. Middle powers and small states, particularly when they work collectively, can shape the policy and behaviour of big powers. The Arctic is no exception.

One way to shake off binary thinking on US–China strategic competition and recognise room for manoeuvre against big power pressure is for Arctic states to realise the significance of their economic connectivity

Managing US–China strategic competition is only possible if Arctic states first do not let such narratives overwhelm their policy thinking. After all, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Canada and Finland did much to build on Mikhail Gorbachev’s Murmansk Initiative for peaceful cooperation in the Arctic. Proposed by prime minister Brian Mulroney in his 1989 Leningrad speech, Canada encouraged the formation of the Arctic Council to manage regional affairs and played an instrumental role in convincing Washington to join the multilateral forum. This fulfilled a long-term aim for Canada, sought since the end of World War II, to avoid becoming caught in the middle of great powers.

Today, strategic rivalry has returned to the Arctic. Most Arctic states are NATO members and, albeit with some friction and concern for the future, largely continue to engage in security cooperation with the US in the region. But there are avenues for multilateral collaboration where American and Chinese pressure upsets the interests of Arctic states. These include intelligence sharing, promoting an Arctic infrastructure fund, and coherence across investment screening policies to minimise security risks and encourage reciprocity with outside partners. In concert, these policies can be leveraged by Nordic states and Canada to direct, deflect and diminish great power competition.

Regional connectivity

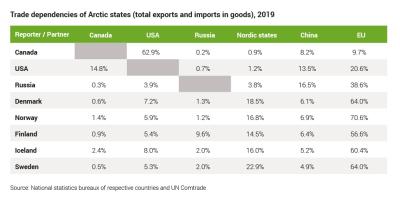

One way to shake off binary thinking on US–China strategic competition and recognise room for manoeuvre against big power pressure is for Arctic states to realise the significance of their economic connectivity. For most Arctic states, trade and investment with the US and China is important. This is particularly the case for Canada’s trade with the US, which makes up nearly 63% of its total trade, and to a lesser extent for Russia’s trade with China. Much of this economic activity may occur outside the geographical boundaries of the region. But what stands out for most Arctic states, the five Nordic countries in particular, is the large share of total trade and investment they have with each other and with the neighbouring European Union (see table). Sweden’s exports and imports to and from its fellow Nordic states, for example, make up nearly 23% of its total trade.

For Greenland and the Faroe Islands, a high dependency on fish exports ties their welfare closely to China, Russia and the United States, but Europe is still vital. For Greenland’s largest corporation, Royal Greenland, Asia made up 34% of total sales in 2019, with China its largest market at 19%, and North America rising sharply in recent years to represent 11%. But Europe still accounts for 31%. For the Faroe Islands, despite lasting tensions from the EU blocking of fish exports in 2013 due to overfishing concerns, EU member states bought over 45% of the Faroese catch sold abroad in 2019. Russia made up 23%, the United States 10% and China 9%.

Nordic and Canadian executives, officials, and academics often exaggerate the importance of economic relations with China. Others assume that because China’s economy is growing and will very likely one day represent the world’s largest, that they will have strong dependencies in the future, and therefore should avoid friction with Beijing on foreign and security policy issues. But this perspective tends to neglect difficulties for foreign trade and investment in gaining access to China’s economy. Beijing is currently pursuing a policy of self-sufficiency to undercut its dependency on foreign imports, and Chinese companies, partly through the Chinese government’s ‘Made in China 2025’ plan, are poised to become even more competitive with those in Europe. Not confronting policy differences with China today, over market access but also on Arctic issues, will only deepen these problems in the future.

Not confronting policy differences with China today, over market access but also on Arctic issues, will only deepen these problems in the future

Even on infrastructure, China is only one of many parties interested in helping to fill the Arctic’s $1trillion gap in port, road, railway, and energy and communications infrastructure. Its engagement will surely increase in the future, but even before American pressure in Greenland, China’s infrastructure activity was largely focused on Russia’s gas-rich Yamal Peninsula and the eastern Arctic. Plans for ports, railway extensions, and underwater fibre-optic cables involving Chinese partners in Finland, for example, are welcome by some but still largely aspirational.

Most infrastructure in the Arctic is still local and developed through national plans. In Russia alone $300 billion in projects are either completed or planned, and Finland, Norway, Canada and the United States are also becoming active. Non-Arctic states may finance and build infrastructure in the Arctic, but regional countries and local communities can do much to support strong governance norms, such as on transparency and financial and environmental sustainability. Denmark and Canada, for example, are collaborating through an Arctic Infrastructure Alliance that can pave the way for new and larger initiatives.

Taming global Arctic

Arctic states and autonomous territories are recognising that the world is arriving at their borders. As Indian scholar Samir Saran argues, ‘as climate change transforms the geography of the Arctic, its waters will merge the politics of the Pacific and the Atlantic Ocean’. Instead of viewing this change as a threat, however, Arctic states can also proactively engage a diverse group of non-Arctic states to reinforce regional norms on future natural resource exploitation and infrastructure development. The European Union, but also Asian middle powers and small states such as Japan, South Korea, India and Singapore, have growing interests in the region, related to climate, energy, rare earths and trade. Despite differences in viewing the Arctic as a global commons, they broadly hold similar viewpoints on advancing international rules-based order.

None of this implies that China should be pushed out of the Arctic. There are avenues to engage China in the Arctic. For instance the China-led multilateral Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. The AIIB has a mandate that extends beyond the continent, and unlike Beijing’s state policy banks such as the China Development Bank and the Export–Import Bank of China, its rules on transparency and sustainability that fit more closely with those promoted by most Arctic states.

The Nordic states and Canada are not pawns in the Arctic; they are players. But in order to avoid great power competition limiting the region’s development, or even fomenting into military confrontation, they should proactively deepen regional and international cooperation that reinforces their security and development norms.

This brief draws on interviews carried out in early 2020 with policymakers from several Arctic states and autonomous territories.

DIIS Eksperter