The Women’s War

I recently visited a migrant graveyard in Sicily, on Europe’s southern border.

In the corner there are 11 crooked, grey tombstones. Under each stone rest ten drowned migrants — identities unknown. Many of them died on April 18, 2015. On that day, an old, blue, wooden ship capsized, and over 800 people drowned. The high death toll marked the start of the so-called “European migration crisis”. It marked Europe’s “ground zero”.

Since then Europe has tried to stop the smugglers. It has paid Libya to hold migrants back in camps, which have been heavily criticized by human rights organizations. It has struck deals with Turkey to stop the migrants and refugees. It has carried out military intervention in the Sahara to stop the migrants there. It has closed refugee camps in EU member states. It has taken away migrants’ residence permits. It has ignored the migrants’ graves, even as they increase year by year on both the European and North African sides of the Mediterranean. Though the “migration crisis” is less and less a crisis or concern in terms of the numbers of migrants, it continues to be a human and political crisis.

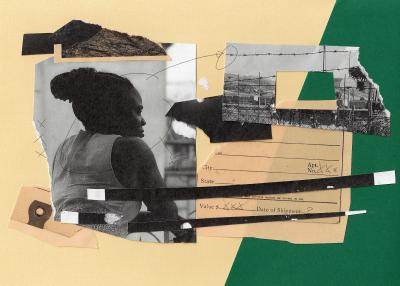

Women’s migration and trafficking across the Mediterranean

The migrants’ tombstones in Sicily made me think of Princess’s route into Europe. Princess is one of the Nigerian women I have been following in my research.

She crossed the Mediterranean on April 6, 2015 — twelve days before the migration crisis. Five rescue ships sailed past her rubber dinghy and a helicopter flew over them before they were discovered.

Trafficking and selling sex in European cities are commonly framed as the main problems for Nigerian women, one that multiple anti-trafficking organizations seek to address, and a situation from which they hope to rescue the women

Princess was nine months pregnant and was crying with relief when she and her unborn child were found.

On April 18, she gave birth to her son, King, on Italian soil, in the arms of an Italian nurse. Princess and King came with the migration crisis. He was born while the others drowned. They came with the crisis and started to build their lives in Sicily.

Princess also arrived in Sicily at a time when there were increased concerns about women like her – Nigerian women who were thought to be crossing the Mediterranean to be sold into “sex slavery” – and about human trafficking, often considered the “dark side” of global migration.

The drownings and the trafficking narrative contributed to a dramatic portrayal of what happens at Europe’s borders.

Indeed, at the port in Sicily I saw how the drama of rescue missions on the high seas and the ritual of disembarkation were observed by the border police, journalists, volunteers, visiting politicians, activists and researchers like myself. And I saw how the IOM, the International Organization for Migration, the UN’s migration agency that receives the migrant women landing at southern Italian ports, carried out its identification of potential victims of trafficking from the long lines of African women who had just crossed the sea.

These actors all take part in some of the most visible and dramatic aspects of European migration politics. Trafficking and selling sex in European cities are commonly framed as the main problems for Nigerian women, one that multiple anti-trafficking organizations seek to address, and a situation from which they hope to rescue the women.

As such, the trafficking of migrant women into the European sex industry has resulted in international headlines and moral panic. This narrative is true for some. But the majority of the women, I meet in Sicily don’t consider themselves as having been trafficked. Nonetheless, like Princess, Nigerian women who have crossed the Mediterranean in the past two decades are often depicted, analyzed and offered assistance in the assumption that they are victims of “trafficking”.

Certainly the reality is that the numbers of Nigerian women crossing to Europe from Libya via the central Mediterranean route did increase significantly from 1,454 in 2014 to 11,009 in 2016, an increase of 600 per cent. From 2015 to 2018 Nigerians were the main nationality among the arrivals by sea in Italy. In 2016, the IOM assisted 768 victims of trafficking in the European Union. Most assisted were of Nigerian nationality (59%) (IOM 2017). The 2017 IOM report focused on the arrival by sea of Nigerian women, the data having been collected by IOM’s personnel in the field (IOM 2017).

There was not only a rise in the numbers, but also changes within the migrant group itself. Prior to 2014, Nigerian women had been older when they arrived (+25), and when they were later encountered in the red-light districts of northern Europe they had usually been in Italy for several months or years before traveling north to look for more profitable work. Now they were going straight to northern Europe with no documents, only a few days after arriving in Italy.

There were also a number of tragic capsizes where larger groups of Nigerian women drowned together on the way. Behind the tragic images of dead women and lines of brown wooden coffins were a reality in which an increasing number of Nigerian women were migrating alone to Europe across the Mediterranean, often engaging in sex work upon arrival. This increase and the changes and tragedies that accompanied them led to social workers, NGOs, the IOM and the UNHCR becoming concerned that the rise was part of an organized trafficking network, a “European trafficking crisis”. The IOM estimated that “about 80 percent of Nigerian women and girls arriving by sea in 2016 were likely to be victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation” (IOM 2017). In my interviews with their personnel they in general considered all the Nigerian women they encountered at the ports of disembarkation as having been trafficked by default.

rather than trafficking they emphasized the high level of unemployment in Nigeria, the falling oil prices in the country and the lack of jobs for their male providers as their motivations

Yet, the high numbers of women identified as having been trafficked were and –are at odds with the daily reality of the Sicilian refugee camps. Here the IOM staff, the NGOs and the women I interviewed, explained that most of the women showed little interest in the anti-trafficking programs that offered to return them to Nigeria through Assisted Voluntary Return Programs or access to different types of skills training in Italy.

The life and death events, the struggles these migrants experience on their journeys to Europe are important in understanding why so few want to return voluntarily, despite this often being a part of the anti-trafficking programs. Having invested so much in the journey makes it more than difficult to return. In the long run some become interested in the programs because that could provide them with a visa for up to five years. But on arrival most try to escape the refugee camps as quickly as possible to start selling sex elsewhere and repay their debt.

In my interviews with IOM and UNHCR staff in Sicily in 2017, they focused on the trafficking networks, how to separate the victims from the traffickers on arrival and how to distinguish minors from adults, as the two groups were eligible for different kinds of assistance.

However, in my interviews with the migrant women in Sicily in the same year, rather than trafficking they emphasized the high level of unemployment in Nigeria, the falling oil prices in the country and the lack of jobs for their male providers as their motivations. They explained that they had migrated “because so many others are going too,” as one young woman told me, echoing many others.

Trafficking, or debt-bonded migration?

Like many of the women here, Princess decided to migrate and to allow herself to be smuggled, having borrowed money for her journey, because she had debts back home in Nigeria. Yet, although debt is a powerful motive for migration, it is often absent from the debates on migration and trafficking.

Debt seems dry and boring compared with sensational stories of the cruelty of human smugglers and human trafficking. Nevertheless, the reality is that migration is very often motivated by debt. As such the hope is that migration will turn out to make long-distance debt restructuring possible. Here we are talking about the millions of families in the Global South that are trapped in a vicious circle of debt, not those fleeing bombs and conflict.

Smugglers, traffickers and migration facilitators then earn money because, in order to finance the journey to Europe and to repay their old debts, many migrant families incur yet more debt to pay for the smuggling.

They said I am only allowed to be here if there is war in Nigeria. But there is no war.I only have my own war. The women’s war. The war in my family is back home

The women are commonly identified as having been trafficked on the grounds that they arrive in Europe with this debt, which they are expected to pay to a madam while they are in Europe.

The women typically finance their journeys from Nigeria by taking out loans of up to €50,000 to pay for false documents, transport and, for some of them, the promisethat someone will be there to receive them and provide them with a job. Most of the Nigerian women are aware that they will have to sell sex to pay off the debt, yet many arrive knowing little about the realities of living in Europe as an undocumented migrant.

Over the years it has become evident that the harder it has become to get into Europe, the more debt these women arrive with, and the more vulnerable they are to those migration facilitators, the madams, the sponsors and sometimes the traffickers who profit from the EU’s strict migration policies. Furthermore, women are not simply being transported as passive victims. Typically, it is other Nigerian women who mediate the loans, find the brothels, andarrange the migrants’ documents, transport and travel itineraries.

Often they have been in similar situations to those they are now assisting and at times exploiting. I meet ever more women who finance their own migration by recruiting or being involved in the migration of others.

Who, then, is the “victim,” and who the “villain”?

Making it in Sicily

Four years later, in 2019, Princess and I are with the border police in Sicily. I sit with King on my lap while she is being told she has ten days to leave Italy. Like thousands of other migrants in Italy, her humanitarian residence permit is not being extended. Italy and Europe want the migrants to return home.

She calls a friend afterwards.

“They said I am only allowed to be here if there is war in Nigeria. But there is no war,” she says. “I only have my own war. The women’s war. The war in my family is back home.”

She shows me the scars on her scalp from her ex-husband’s violence. Her women’s war also consisted of being an unemployed, single mother who had to find a way to provide for two children in Nigeria. It has been seven years since she left Nigeria, having left her children with her mother to look for work in Italy. “I can only rest my head when I see them again,” she says.

Wars take many shapes. But the women’s war is one that is rarely deemed worthy of asylum.

We go to the overburdened migrant relief center on the island.

“Your son is your only chance to stay in Italy … but then you have to demonstrate that you are a good mother,” says the lawyer.

He hooks his two forefingers together to signify a child attached to its mother.

“You have to be with him all the time.”

Outside, Princess asks me a question, exasperated.

“How can I be a good mother when I don’t have a job and live in a refugee camp?” she says. “That is not what the Italians mean by being ‘a good mother.’”

Some of the migrants I meet finally get jobs as dishwashers. The jobs last two months at a tourist resort outside a small, picturesque Sicilian city. They get paid 3.5 euros an hour.

He trudges behind her into a market. She chooses a large yam, a frozen chicken, and three tins of tomato sauce. He pays and gets her number. The Italian men pay 50 euros for sex; the African men get it for 20

Many of the migrants I meet think that there are now too many of them in Italy. It doesn’t help to go to the bigger cities. Palermo, Turin, Naples – there are far too many unemployed people there. But the borders to northern Europe are closed for migrants. Some begin their journeys northwards over the mountains, by foot, under the radar.

One day, a young Nigerian man asks Princess for her phone number. She turns her head, looks me in the eyes, and says, “Look at me now. This is how I survive.”

She turns to him. “If you want my phone number, you have to buy something for me,” she says flirtatiously.

He trudges behind her into a market. She chooses a large yam, a frozen chicken, and three tins of tomato sauce. He pays and gets her number. The Italian men pay 50 euros for sex; the African men get it for 20.

During the day, the women sleep in small, warm dorms in the refugee center, with thick blankets pulled over their heads.

“We sleep during the day. There is nothing else to do here in Italy,” I hear.

One of the more experienced women says: “My solution? Women’s built-in ATM machine.”

Critical trafficking research

Transnational feminist scholarship and critical trafficking studies are some of the literary strands of research, drawing upon ethnographic research into migrants’ perspectives and experiences, that have complicated the understanding of human trafficking as merely a question of crime, exploitation and degradation. For example, by criticizing how a focus on prostitution as inherently and universally a matter of violence against women, commonly mutes other factors that the involved women themselves might find just as crucial, if not more so, such as racism, sexism or a lack of employment.

Much policy is directed at dismantling and prosecuting the criminal networks that are assumed to be the main force behind facilitating “illegal” migration and the exploitation of migrants. Claims that criminal human trafficking and smuggling networks constitute the third largest illegal economy after the trade in drugs and weapons abound. In this perspective, human trafficking is ultimately driven by the cynicism of traffickers luring migrants into danger and is thus a question of victims versus perpetrators. Prosecution is important, but in order to improve our understanding of “trafficking,” we need to understand women like Princess and explore the links between migration politics, labor, exploitation and gender.