When jihadists broker peace

Following Mali’s coup d’état of 18 August 2020, the transitional government is yet to present a roadmap for peace in central Mali outlining a new strategy for dialogue with armed non-state actors. To support this process, it is important that Mali’s international donors identify already-existing local peace agreements and support local-level dialogue with all parties to conflicts.

- Immediate de-escalation of conflicts is needed through disarmament of militias and rebuilding of trust between local communities and Mali’s armed forces, with a strong focus on protecting civilians.

- Mali needs a national, comprehensive strategy for how to include jihadists and local militias in dialogue, reconciliation and dispute resolution.

- International donors need to identify already-existing local peace agreements and support local-level dialogue between all parties to conflicts.

- Long-term solutions regulating equal access to natural resources for different population groups are key.

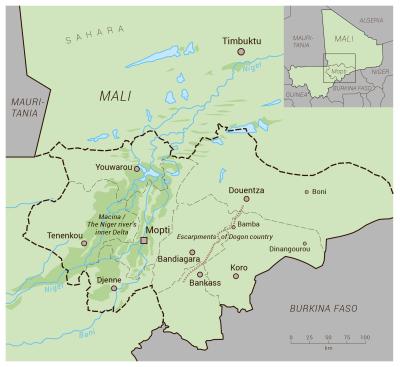

Since 2015 Mali’s expanding security crisis has escalated in the country’s central region, Mopti, aggravated by local conflicts over natural resources with longstanding political roots along with lawlessness and growing economic criminality. As jihadist groups under Al Qaeda and the Islamic State in Greater Sahara settle into newly conquered territories, jihadists, self-defence militias and the security and defence forces commit atrocities against the local population. Yet, recently, jihadist groups seem to be succeeding in brokering local peace agreements through violent oppression. If the state is to take back control of jihadist-controlled areas, a new social contract between the state and its local populations that tackles the existing social, economic and political grievances is needed.

The crisis in Mopti is an extension of the insecurity that has plagued northern Mali since 2012. After being chased out by French counterterrorist and UN stabilisation interventions in Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu in 2013–14, armed groups invaded various localities in Mopti. In this context, jihadists and self-defence militias use attacks on the population’s livelihoods and access to resources as a weapon of war to control communities and to finance criminal activities. Attacks include extortion, plundering, the burning of huts, granaries and villages, looting, and slaughtering of livestock. The three-year-long disruption of agricultural production is causing displacement and widespread hunger in the population.

Background to the conflict

The local rural economy depends on seasonal access to key natural resources, which has been affected by extreme climate events and droughts in the last thirty years. For centuries, different population groups – Fulani and Tuareg herders, Bozo fishermen and Dogon farmers – have competed and collaborated over complementary resource use. However, in the last two decades, corrupt elite practices and mismanagement have fuelled frequent but limited conflicts over access to land, grazing and fisheries. Tensions and social unrest have also been caused by the highly stratified social relationships that exist within and between the groups, which have sustained feudal structures of corrupt elites and their deprived beneficiaries. In the wake of a jihadist resurrection, these tensions have become violent and led to the mobilisation of the population into various armed groups.

The Niger River divides the Mopti region into two interdependent agroecological areas: the flooded inland delta and the drylands. The ecosystem of the inland delta enables grazing, fishing and cultivation. In the rainy season, from July–October, the flooded area extends to 30,000 km2 which forces the herds into the drylands, while rice cultivation takes place in the flooded area. As the water recedes the herds return to the delta to graze in the bourgou (a grass species) fields. The delta contains about 70 per cent of Mali’s irrigated land and in the dry season more than three million cattle graze there.

The main armed actors in Mopti

Jihadist groups include various subgroups of Islamic State in the Great Sahara (EIGS) and the regional Al Qaeda branch, Jama'at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM). These groups capitalise on poverty and a sense of abandonment to recruit, particularly among Fulani herders. Fighters from in and outside the region, including Fulanis from Niger and Burkina Faso such as Ansaroul Islam, have joined the jihadists in Mopti. The disproportionate presence of Fulani among jihadists has ruined inter-community trust and subjected all Fulani to unprecedented stigmatisation, even though the jihadists among the Fulani are a minority.

I joined the jihadists because they offered me a salary twenty times higher than the one I earned from herding livestock for a village notable. For four years I lived in the bush with them. They often gave me drugs (tramadol). I cut the throats of and killed dozens of people during the attacks on villages. That’s why I deserted. Today, I am plagued by regret and nightmares.

To protect themselves from the jihadists, many Dogon and Bambara communities have created self-defence militias such as the Dan Na Ambassagou militia (‘the hunters who trust in God’) who declared war on the jihadists and attacked Fulani civilians accused of supporting the jihadists. Dan Na Ambassagou, which attracts retired mercenaries from the region (Cote d’Ivoire and Liberia), are accused of being informants for the government forces. Contesting the violence of Dan Na Ambassagou, some Dogon groups have formed yet other self-defence militias, such as Dana Atem.

In Mopti the first half of 2020 was the most violent period, with an average of ten attacks per week and a total of 877 people killed (ACLED databases, 2019; 2020). In February 2020, there were over 56,000 internally displaced people in Mopti out of an estimated population of 1.6 million (OCHA, 2020).

Mali’s security and defence forces (SDF) have been accused of extrajudicial abuses of civilians, especially the

Fulani, whom the SDF also accuse of being jihadists or collaborators of jihadists. In the first trimester of 2020 the UN reported more than 100 civilians killed by the SDF. Due to the many jihadist attacks on military outposts, the SDF is concentrating in larger bases, while withdrawing from areas in dire need of protection.

Where the state is absent, jihadist groups control some areas by introducing new, often violent, rules and institutions for regulating disputes and access to key natural resources. Moreover, in the epicentres of communal violence between Dogon and Fulani groups, the jihadists have successfully brokered local peace agreements. In contrast to several internationally supported local peace agreements that exclude the jihadists, the jihadists broker agreements that seem to last beyond short-term ceasefires.

Jihadist peacebuilding in the drylands

Jihadists control large parts of the Koro area with support from Ansaroul Islam fighters from across the border with Burkina Faso. For nearly three years violent clashes and economic oppression have caused serious food shortages and broken historical ties between the Dogon and Fulani communities. The jihadists have operated by surrounding the Dogon’s fields and threatening to attack them if they enter, and by setting up roadblocks to prevent Dogon villages from accessing food supplies. In revenge, the Dan Nan Ambassagou militia have attacked Fulani herders and prevented them from accessing Dogon villages, markets, schools and health facilities. They have also introduced taxes and garrisons in Dogon villages.

The important thing is to save lives. There is no such thing as a bad peace.

In response to these tensions, in July 2020 the Dogon villagers organised to negotiate with the jihadist leaders. To convince the jihadists to lift the embargo, the community representatives invoked the historical links and blood pacts between the Dogon and Fulani communities. Finally, the jihadists implemented a peace agreement that has ended intercommunal violence and to which, so far, both Fulani and Dogon parties have adhered. The jihadists set several conditions to allow farming, logging and herding, namely: to expel Dan An Ambassagou; a ban on arms; introduction of sharia-based family laws and taxes; a ban on any contact with the Malian state and army; and respect for customary agreements governing the use of land and resources. According to our sources, people have diverging opinions about the agreement. Some speak of an obvious power imbalance between the Dogons and the jihadists. Others believe that the agreement is an opportunity for peace.

Jihadist embargo in the Delta

Initially invisible, jihadists are now omnipresent along the Niger riverbanks. The villages are emptying and, during high waters, the jihadists stop canoes to attack travellers and loot goods. Their network of informants invades the markets.

Some 300 kilometres from the escarpments of Dogon country another kind of jihadist settlement took place after the Malian army (FAMA) was deployed in Djalloubé in 2018 to strengthen security in the Delta region. Jihadists managed to turn the population against the armed forces by imposing embargos and blocking movements to and from the villages. They also kidnapped and assassinated several people and banned traditional fisheries and access to agricultural fields.

After a year, the village notables formed a commission of 20 people to negotiate a lifting of the jihadist embargo. After three months, a minimum agreement was reached with hard restrictions. The jihadists ordered the population to break with FAMA, which the jihadists considered to be Dahoutou (authorities of evil) and to return to sharia and jihad. In return the population was allowed access to food supplies and to resume agricultural and fishing activities.

Supporting local mediation efforts

These examples of locally-brokered peace agreements have so far received scant attention from international actors in Mali. While international support has been given to local-level dialogue, this has often been pursued in an uncoordinated manner and with few lasting results. To enhance these efforts, Mali’s international support partners should begin by identifying the already-established local peace agreements, based on participatory dialogue with family and community representatives, religious and customary authorities and local conflict mediation experts. In doing so it is important to avoid biased approaches through basing engagement on in-depth, context-specific knowledge of social political practices and cultural–religious beliefs. Building trust and ensuring broad participation by facilitating negotiations between community members, traditional, customary and religious and armed non-state actors is also necessary to redress the current imbalance in natural resource management. This also means redefining the role of local institutions in the sustainable resolution of inter-community conflicts.

Given the strong position of jihadist groups in conflict-affected areas, and to avoid obstruction, it is important to consider how to include jihadist groups in local negotiations and peace agreements. This involves bridging peacebuilding efforts and supporting dialogue and reconciliation.

DIIS Experts