To UN or not to UN

Since the Balkan wars in the 1990s, the Nordic states have been reluctant to use the UN as a conflict management tool. However, they are presently all contributing to the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Does this signal a comeback of Nordic support for UN peacekeeping? Probably not.

Recommendations

■ The Nordic states must provide what the UN needs, extending beyond symbolic contributions.

■ If not, the Nordic states must consider the strategic consequences of their current approach to UN peacekeeping. Continuing with no or limited contributions is a rejection of the legitimacy and relevance of the UN as a peacekeeping framework.

As the Cold War came to an end UN peacekeeping underwent a radical change. Its remit transformed from one of maintaining ceasefires to include multi-dimensional engagements in states emerging from war through a range of measures, including the deployment of soldiers, but also the organisation of elections and building of democratic institutions.

For the Nordic countries, the UN of the 1990s represented a natural and attractive framework for supporting peace operations globally. Indeed, it appeared an ideal avenue for the outward promotion of values related to the Nordic welfare state model, which was considered a legitimate and worthwhile foreign policy objective in the early 1990s.

The Nordics were thus staunch supporters of the transformed and growing role of UN peacekeeping taking place between 1989 and 1993. For instance, Denmark became the largest per capita troop contributor to the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina and dispatched an armoured squadron to Bosnia-Herzegovina as part of a Danish–Norwegian–Swedish mechanized battalion (NORDBAT 2).

However, the role of Nordic states as the darlings of UN peacekeeping soon came to an end.

Srebrenica: A Definitive Turning Point

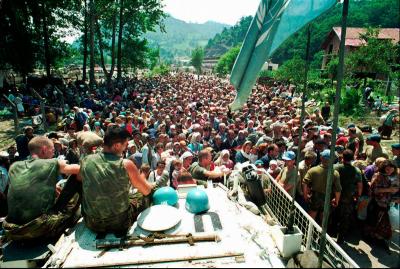

A decisive turning point in not just Nordic, but general Western willingness to make troop contributions to UN missions came with the events of July 1995 in Srebrenica, a small town in the north-eastern corner of Bosnia-Herzegovina on the border with Serbia. In short, Bosnian Serbs rounded up and executed more than 8,000 Bosniaks (Muslim Bosnians), primarily men and boys, while 370 Dutch UNPROFOR soldiers stood by, unable or unwilling to intervene.

Events in Srebrenica in particular, but also the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, highlighted two major trends in peacekeeping as it had evolved up until that point. First, they demonstrated how quickly the UN had taken on a wide-ranging role in post-Cold War international conflict management, with a dramatic expansion in the number of missions and peacekeepers. Second, they showed the limitations of deploying lightly-armed peacekeepers in war zones who were only allowed to use force in self-defence. They proved unable to prevent mass killings in Srebrenica, and even had difficulty protecting themselves.

In 1995 UNPROFOR handed over the responsibility for enforcing the Dayton Peace Agreement in Bosnia-Herzegovina to NATO. This constituted a partial departure of the UN from its role as the ‘go-to organisation’ for conflict resolution internationally. Not only had the image of UN peacekeeping taken a major hit with events in the Balkans, but its role in Europe was also dwindling with NATO’s takeover from UNPROFOR. As one high-ranking Danish military officer retrospectively noted in 2017: “The Danish military began to lose faith in the UN as a credible peacekeeping actor after [Srebrenica]”.

All the Nordic countries sharply reduced their contributions to UN peacekeeping operations after 1995, cementing a trend that has continued up until today: a reorientation towards civilian and military operations led by the EU and NATO respectively.

For the Nordic countries, NATO, which had overcome its post-Cold War identity crisis of the 1990s, offered the opportunity to strengthen their national defence forces and ensure territorial protection. When the EU emerged with a new conflict management framework in 2003, it offered a way to pursue long-term, civilian and soft-power interventions that were not unlike UN peacekeeping missions. It was also the case that the operations led by these two more narrowly and regionally-focused organisations were considered of more direct relevance to Nordic and broader European security.

The War on Terror, Afghanistan and Iraq

The prioritisation of NATO was consolidated following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the US, and the War on Terror that ensued in Afghanistan and Iraq. Combined with UNPROFOR’s earlier troubles in the Balkans, this shift of attention by the global North towards counter-terrorism and the interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan only accentuated that NATO was in a far better position to ensure a robust approach to conflict management. UN peacekeeping was not exclusively, but certainly primarily, of relevance to protracted conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the case of Denmark, the country’s turn to NATO matched an emerging Danish self-perception as an active military player globally. Up until this point, in contrast, the UN had emphasised impartiality, neutrality and non-use of force except in self-defence. The relevance of the UN took a further hit following the crisis in the Security Council caused by the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the controversy surrounding the Libya intervention in 2011.

The bottom line is that few uniformed personnel from the Nordic countries have participated in UN-led peacekeeping, being otherwise engaged in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan; that is, until Mali.

Nordic Comeback in Mali?

Today, troop contributions to UN missions are almost exclusively made up of non-Western states, primarily from Africa and Asia. However, when the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was deployed in April 2013, it marked the return of Europe to UN peacekeeping. This was for two reasons in particular.

MINUSMA does not constitute a new-found Nordic inclination to contribute to conflict management via the UN. Rather, the decision to deploy with the UN in Mali was made on geopolitical grounds and is based on a political wish to show continued support to UN efforts in the Sahel.

First, the large-scale US-led missions in Iraq and Afghanistan had been downsizing for some time. This meant that a growing number of soldiers and concomitant resources were freed up to deploy elsewhere (for different reasons, the end of the Cold War also freed up resources). Second, Mali as a hotspot for trafficking of drugs, people (migrants and refugees) and arms is considered to be in Europe’s backyard and, seen through this lens, a complete breakdown of the Malian state would be a direct threat to European stability.

Furthermore, MINUSMA is an example of a new type of peacekeeping mission. It constitutes a growing robustness in the use of force by the UN, with a mandate aimed at enforcing peace, not keeping it. This represents a considerable transformation of UN peacekeeping since the early 1990s. However, MINUSMA also exposes the challenges that the UN faces when it comes to operating in open conflict.

Seen against this background, MINUSMA does not constitute a new-found Nordic inclination to contribute to conflict management via the UN. Rather, the decision to deploy with the UN in Mali was made on geopolitical grounds and is based on a political wish to show continued support to UN efforts in the Sahel (without full and robust engagement).

Choosing the UN symbolically is not enough

Norway deployed five specialist and niche capabilities to MINUSMA, which served to project its image as a ‘peace nation’ whilst acknowledging Mali as an arena of both counter-terrorism efforts and robust peacekeeping.

The Danish contribution to MINUSMA was more significant because as well as marking a Danish return to UN peacekeeping a Dane, Lieutenant General Lollesgaard, was appointed Force Commander of the mission in 2015–2016. However, the military contribution ended up being symbolic and made only a limited operational difference.

Danish politicians did consider deploying a transportation convoy (100+ soldiers), which the UN had requested. However, they eventually opted for a much smaller contribution: a C-130 transport aircraft and a special operations unit (of which one was already contributed by the Dutch, for instance).

Although the political will to participate in UN peacekeeping endures, as an interview with a Danish official suggests, this is in order ‘to tick the right boxes’. The UN might be recognised symbolically but, unlike NATO, it is not seen as an effective instrument from a military perspective.

Lack of robustness of UN peacekeeping in the 1990s drove the armed forces of the Nordic states away from the organisation. Ironically, the present expanded will of the UN to use force in peacekeeping operations contradicts what was the attraction of the UN framework immediately after the Cold War, namely its peaceful, neutral and non-violent approach to international conflicts. There is a strong sense among the Nordic states that the UN is not up to the task in Mali, and their hesitation has been reinforced, not eased, by engaging in the mission.

However, as the only truly global organisation, it may also be the best option when it comes to solving matters of global peace and security. Making symbolic contributions is insufficient. This means that the Nordics must step up their UN game if they want to ensure its continued relevance.

DIIS Experts