The future of nuclear energy in the Baltic Sea Region

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put the issue of energy supply at the top of the EU’s security agenda, leading to a drastic policy shift in energy relations with Moscow. Similarly to other European states, countries in the Baltic Sea Region (BSR) are struggling to phase out Russian fossil fuels and accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy amid skyrocketing energy prices.

Although there are no quick fixes, the challenge of the dual energy and climate crisis in a tense geopolitical context has triggered different policy responses across the region, with national policies increasingly pointing to the nuclear energy sector.

Shifting public attitudes: Denmark

Denmark has always stood out as being strongly anti-nuclear. Faced with strong societal opposition to nuclear energy in the 1970s-80s, the Danish government ruled nuclear energy out of public planning in 1985. This policy was further strengthened following the 1986 Chernobyl accident and prevailed for decades thereafter. Strong pressure from Denmark also contributed to the decommissioning of the Swedish Barsebäck reactors near Copenhagen in 1999 and 2005. However, today 40% of the Danish electricity imports from Sweden are of nuclear origin.

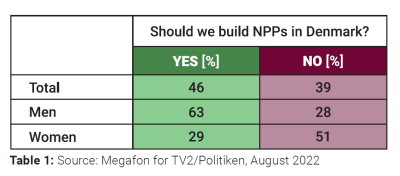

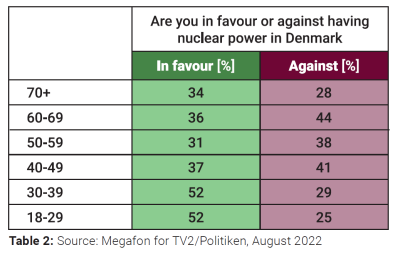

The general anti-nuclear energy policy course prevails, as the Danish government plans a mass scale-up of wind energy to tackle the energy crisis. However, public attitudes have been significantly affected by recent climate and geopolitical considerations. While in 2007 around three-fourths of the Danes were against nuclear power, a study conducted by Megafon for TV2/Politiken in March 2022 revealed that 39% of respondents were in favour and 43% against building NPPs in Denmark. A subsequent poll carried out in August 2022 revealed that, for the first time ever, the declared supporters of nuclear energy in Denmark (46%) outnumbered its opponents (39%).

These changing attitudes vary drastically across different demographics. While the majority of younger Danes declared support for nuclear energy, the strongest opposition remains in the 60-69 age group. Additionally, Danish men are twice as likely to support nuclear energy development as compared to Danish women (See tables 1 & 2). It remains to be seen whether this recent shift in attitudes will persist and alter the course of the Danish energy policy. In the BSR at large, the combined effect of the energy-climate crisis and changed geopolitical context increasingly pushes state and non-state actors to turn to nuclear energy.

Building new NPPs

Finland plans to phase out coal by 2029 and become carbon-neutral by 2035. The country is expected to become self-sufficient in electricity generation by 2023-4 through an increase in wind power, and the Olkiluoto 3 nuclear power plant (NPP) entering commercial operation in late 2022. Currently, the five nuclear reactors account for one-third of domestic electricity production.

The majority of Finns have also consistently supported nuclear energy over the last three decades. According to a recent opinion poll (2021), half of the population supports the further development of nuclear energy, 24% think that it should stay at the same level, and only 18% think that the share of nuclear energy should decrease. Even the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster only had an indirect impact on the Finnish nuclear energy sector with the German company E.On. withdrawing from the construction of the sixth nuclear reactor in Finland.

Subsequently, Russian state-owned corporation Rosatom became involved in the project in 2013 as a supplier of a nuclear reactor and fuel. It also became a financier and shareholder in the Fennovoima nuclear power company (comprised of Finnish state-owned companies) which was in charge of the project. Rosatom’s involvement raised domestic criticism in Finland, especially after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Nevertheless, the Finnish parliament approved Fennovoima’s project plans with Rosatom’s involvement in the same year. The Hanhikivi 1 nuclear reactor was scheduled to open by 2029. Although the Finnish Ministry of Defense ordered a geopolitical and geoeconomic risk analysis of the project in 2021, it was only after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine that Fennovoima terminated the contract with Rosatom’s RAOS Project subsidiary. The official explanation quotes significant delays as the reason for the termination.

Sweden replaced its high dependency on oil with nuclear and hydro energy in the mid-1970s, amidst the global oil crisis. However, public opposition to nuclear power quickly grew. Following the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in 1979, the Swedish government held a referendum in 1980 which stopped further expansion of the domestic nuclear sector and led to a scheduled phase-out of the country’s 12 nuclear reactors. Two reactors in Barsebäck were decommissioned in 1999 and 2005, followed by two units in Oskarshamn in 2016-17, and two units in Ringhals in 2019-20. While the Barsebäck reactors closed largely due to pressure from Denmark, the shutdown of the others was due to economic considerations – low electricity prices in Sweden prior to 2020 and the expensive modernization costs required in order to comply with the increased nuclear safety standards resulting from the nuclear accident in Fukushima in 2011. The remaining six nuclear reactors (in Ringhals, Oskarshamn, and Forsmark) that generate around one-third of the domestic electricity supply, were modernized with increased thermal capacity and safety features.

The war in Ukraine in 2022 led to a spike in electricity prices and fuelled the domestic debate on nuclear energy in Sweden. Recent polls from 2022 also showed that 60% of Swedes support new nuclear reactor development to expand low-carbon energy. As such, conservative parties used pro-nuclear rhetoric in the 2022 election campaign, promising increased funding for nuclear R&D.

In mid-October 2022, the incoming right-wing government announced plans to build new NPPs to help meet the rising electricity demand.

Faced with the daunting task of phasing out coal, which still accounts for 70% of electricity generated domestically, Poland decided to proceed with nuclear energy development in the mid-2000s. The nuclear plans were already on the governmental agenda in the 1970s and Poland started the construction of its first NPP in the 1980s. This project was officially abandoned in April 1990 due to strong local societal opposition, the Chernobyl accident, concerns over nuclear safety, and technical delays. However, the decision was not final, and the plans resurfaced in 2005.

Currently, Poland plans to build six 1 - 1.5 GW units, with the first NPP scheduled to be commissioned by 2033 and each successive unit to follow every two years thereafter. By 2043, the six reactors are meant to cover around 20% of the domestic electricity demand.

Public support for nuclear energy is currently at an all-time high. In 2006, 56% of Poles opposed nuclear energy. In 2020, an opinion poll conducted for the Ministry of Climate showed that 62.5% of the population was in favour of it. The outbreak of war in Ukraine and the ongoing energy crisis have further strengthened these attitudes. In August 2022, 64% of Poles declared that they want the nuclear energy program to be accelerated.

Phasing-out nuclear energy

Not all states at the Baltic Sea pursue nuclear energy development policies.

Lithuania had to decommission its two Chernobyl-type reactors in Ignalina in 2004 and 2009 as one of the conditions for EU membership, even though nuclear power amounted to 60-75% of electricity generated in Lithuania in 1990-2009. Following the closures, Lithuania became a net importer of electricity and experienced soaring prices. Although a new NPP project has been considered since that time, it never came to fruition.

Germany initially planned to phase out coal by 2038, cover half of the electricity production with renewables by 2030 and become climate-neutral by 2045. It also aimed to achieve a full nuclear phase-out by 2022, a deadline agreed upon among the German political parties following the nuclear accident in Fukushima after which time the seven oldest German NPPs (out of 17) were taken off the grid with the remaining ones meant to be closed within the following decade. Germany’s ambitious Energiewende ruled out both the use of coal and nuclear in the long term, which turned gas into a particularly important ‘bridge fuel’. Being highly dependent on gas from Russia (55%), Germany was heavily hit by the energy crisis which also put into question its nuclear phase-out timeline.

With three nuclear reactors decommissioned in 2021, the remaining three were supposed to be shut down by the end of 2022. Two of these reactors are located in the South, where an alternative electricity supply is insufficient, making this particularly tricky. Consequently, in September 2022, the Minister of Economy announced that NPPs in the South (Neckarwestheim in Baden Württemberg and Isar 2 in Bavaria) would remain in operation until mid-April 2023. Given the discrepancy between demand and supply in the South, the problems with transmission grids (for sending electricity from windfarms in the north southwards), and the impact of the recent energy crisis (gas crisis, lower electricity output of French NPPs, and lower hydropower output due to droughts in Europe), prolonging the operational life of these NPPs beyond April 2023 is plausible. However, the shortage of nuclear fuel, which is expected to last until late 2022/early 2023, remains a limiting factor.

Rethinking nuclear: Small modular reactors

The development of new conventional NPPs is not the only focus of the current energy policies in the BSR, as countries are increasingly turning their attention to small modular reactors (SMRs).

Finland is exploring the potential use of SMRs for district heating and electricity generation. A 2021 resident survey in the Helsinki Metropolitan area found that 46% of the population was in favour of SMRs in their area, while 31% opposed their presence. This support is driven by climate considerations, as over half of the respondents agreed that SMRs are needed for sustainable development and nearly half agreed that they are an essential part of future energy systems.

In Estonia, the government set up a nuclear energy working group in 2021, and in 2022 signed a strategic cooperation agreement with the US to develop nuclear capacity using SMR technology. The project is being developed by a private company Fermi Energia, which plans to build four 300MW reactors (envisioned to meet all domestic electricity demand), with the first one becoming operational in 2032.

Similarly, in Poland, several energy-intensive industrial companies have been exploring the possibility of investing in SMRs to replace coal-fired power plants. The outbreak of the war in Ukraine in 2022 coincided with the signing of the agreement with the US company NuScale Power and Polish copper and silver producer KGHM Polska Miedź SA to deploy the first SMRs in Poland by 2029.

In Sweden, a new center of competence in nuclear technology was established at Uppsala University (2022-2026) with the purpose of supporting the development of a knowledge-based strategy for introducing SMRs in Sweden. The center is co-founded by the Swedish Energy Agency, academia, businesses, and the public sector.

In April 2022, Latvia announced that it was joining the Biden administration’s Foundational Infrastructure for Responsible Use of Small Modular Reactor Technology (FIRST) program that aims to advance technical collaboration on nuclear energy infrastructure.

Denmark, although largely anti-nuclear, is home to two nuclear start-ups – Seaborg Technology and Copenhagen Atomics, that are independently developing molten salt reactors, albeit not intended for the domestic market.

Although national nuclear energy policies differ vastly across the BSR, significant investments in both traditional and new nuclear technologies are being envisioned to tackle the energy-climate crisis within a new geopolitical reality. The long-term challenges of nuclear energy such as nuclear waste remain an issue for both the states that invest in new NPPs (e.g. with Finland granting a license for the construction of a facility for spent nuclear fuel in Olkiluoto by 2025), as well as those who proceed with nuclear phase-out (e.g. with Germany planning to identify a new final storage site for nuclear waste by 2031 that could enter operation by 2050).

DIIS Experts