Small states’ security strategies need an international energy dimension

-

Small states should include energy in strategic documents pertaining to foreign and security policies, as energy is a tool in the security toolbox of the great powers.

-

Self-sufficiency in energy does not mean that a country is shielded from the dynamics of international energy.

-

Small states should strive to build enduring political alliances focused on energy.

-

Small states should prioritise sending experts to the NATO Centre of Excellence for Energy Security in order to stay on top of the international security situation concerning energy.

Denmark encountered a number of unforeseen obstacles when negotiating the Nord Stream and Baltic Pipe gas pipelines, and the country ended up standing exposed and alone. A better politics of energy alliances and better strategic preparation are key lessons for small states like Denmark when dealing with the problematic combination of security and energy.

Denmark has been self-sufficient in its energy supplies since the mid-1990s, and energy has been dealt with largely as a technical issue pertaining to the accessibility, affordability and accountability of energy sources. This position fed into an understanding of energy crises as something that largely happened elsewhere.

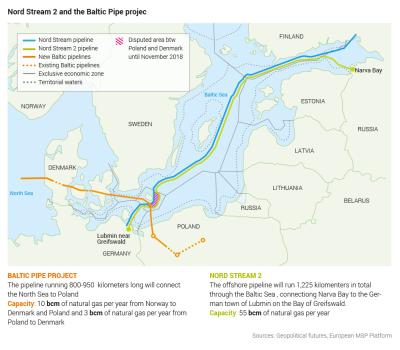

So, when Denmark got caught up in international energy geopolitics concerning the two Nord Stream pipelines that are intended to bring natural gas from Russia to northern Germany, and when the Baltic Pipe planned to start pumping Norwegian gas to Poland, the country had to make up a strategy on the go. Being self-sufficient in natural gas from the Danish gas fields in the North Sea, the issue for Denmark was not the gas: the problems of the Nord Stream and Baltic Pipe were almost exclusively political for Denmark. Taking the three negotiating processes as examples of how Denmark developed strategies on the go, other countries can learn from the Danish experience.

(Russian) energy as a weapon

Energy is a central aspect of the security strategies of the great powers. Smaller countries like Denmark should take this into account when formulating security strategies to avoid contributing to overdependence on a single energy supplier and the vulnerability this entails.

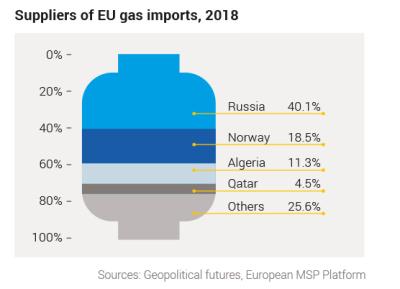

As far back as the 1990s, the Russian prime minister Yevgeny Primakov announced that Russia would use energy as a weapon in its foreign-policy toolbox. The Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines should therefore be seen as a way for Russia to gain the upper hand in the European region. The EU currently imports almost 40% of its natural gas from Russia through pipelines running through Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic Sea. This has led many countries, especially in eastern Europe and the Baltic region, to sound the alarm: too much dependence on Russian energy is considered risky. Indeed, Russia has several times showed its willingness to use energy as a weapon, as in 2006, when a gas dispute ended in the transit of gas through Ukraine being shut down in the midst of a cold winter.

Nord Stream 1 was considered normal politics

In 2009, Denmark became the first country to agree to Russia laying pipes in the Baltic Sea. At this time, all other countries bordering the Baltic, except Russia and Germany, were opposed to plans to pump 55 billion cubic metres of natural gas from the Russian town of Vyborg to Lubmin near Greifswald in northern Germany. Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland all opposed the project for various reasons, including the danger of Russia using the pipeline as a way to obtain military intelligence.

In Denmark, the calculation was different in kind. After Denmark had hosted the World Chechen Conference in 2002 and had played a role in ensuring the accession of new eastern European member states to the EU, the Danish-Russian diplomatic relationship deteriorated.

All in all, Denmark was largely caught unprepared in this story of gas geopolitics

The incoming prime minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen (who replaced Anders Fogh Rasmussen), was much less of a knight of principles than his predecessor. So, when the Russian-owned gas company’s application landed on his desk, he saw a political issue that could be dealt with pragmatically. The benefit would be a better diplomatic relationship with Russia and perhaps new export opportunities for Danish companies.

The result of the change of prime minister in Denmark was approval of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline construction in late 2009. Indeed, after heavy Russian PR work, all approvals were obtained in the region. The first Nord Stream pipeline was ready to send natural gas from the Yamal Peninsula to Germany in 2011.

Denmark is caught standing alone

In short, Denmark saw Nord Stream 1 mainly as a means of improving relations with Russia and largely ignored the security aspect. Fast forward to 2017, when the application for Nord Stream 2 landed on a desk in the Danish Energy Agency. By now Denmark had become much more hesitant towards Russia, as had the rest of Europe, largely due to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, which was a wake-up call for Western countries.

Denmark’s Baltic neighbours had long argued that energy was not just a mundane commodity: it could also be used to destabilise other countries. The EU had created an ‘Energy Union’ in 2015 with the open goal of reducing its dependence on Russian gas imports. Furthermore, American appeals to the Danish government to withstand Russian pressure were growing stronger by the day. Denmark could no longer continue to see energy as just a way of increasing trading relations with Russia or a political issue to be dealt with through the normal channels. The security aspects of energy slowly emerged as a national security issue in Denmark, but there was no explicit strategy in place.

Cold War experience taught that small countries often defy ‘singularisation’, or the situation of being caught standing alone in front of the enemy. This, however, is effectively what happened in respect of Denmark’s handling of Nord Stream 2: the country was left alone as the forward post for months due to the lack of a clear strategy and solid alliances on energy issues.

The Danish Parliament rushed to do something. As the only country that was being asked to build in its territorial waters, Denmark began to seem like the decisive nail in the coffin for Nord Stream 2. However, at that time Danish legislation did not specify that foreign and security issues could be taken into account when making decisions about underwater pipelines. A change in legislation concerning the continental shelf to include foreign and security issues in evaluating underwater pipeline construction sought to remedy this.

The difference between territorial waters and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is that the first confers full sovereignty over the waters, whereas the second is merely a ‘sovereign right’ which refers to the coastal state’s rights below the surface of the sea.

However, even though the legislation was passed in November 2017, it did not solve Denmark’s problem. It bought it some time, but also extended the time Denmark was ‘singularized’, i.e. isolated. The NS2 consortium was impatiently awaiting an answer from the Danish Energy Agency. In August 2018, the consortium submitted another application for the pipeline. This time the route would go northwest of the island of Bornholm through the exclusive economic zone (EEZ). It would therefore avoid Danish territorial waters, and the new continental shelf legislation would not apply.

Denmark capitalized on the Russian energy threat

Underneath the surface, a new pipeline project emerged as yet another complication in the pipeline debacle for Denmark. Poland had long wanted to stop depending on piped Russian gas and had gone shopping for gas elsewhere. The ‘Tommeliten’ gas field in Norway was considered a great opportunity, only Denmark was in the way. Geographically, that is: in order for the Norwegian gas to reach Poland, the Baltic Pipe had to run across Danish land and sea.

Unfortunately, since the 1970s, Denmark and Poland have had an ongoing border dispute due to large overlapping claims to the EEZ. As a consequence, there was no clear jurisdiction in the Baltic Sea south of the island of Bornholm. For the Baltic Pipe to be built, a solution had to be reached. This meant that Denmark was in trouble over the Nord Stream 2 pipeline and now also over the Baltic Pipe, both of which were to run through the disputed area between Denmark and Poland.

Clearly recognizing that Poland was seeking to break free from its dependence on Russian gas, in 2018 Danish diplomats were successful in ending an almost five-decade long border dispute with Poland. Denmark capitalized on the Russian energy weapon in the border negotiations, the end result being that Poland gave up more than 80% of the disputed area in the EEZ – a huge success for peaceful border negotiations, and for Denmark. However, it became increasingly clear that the Danish side was laying the road as they were walking along it. There still seemed to be no clear strategy behind the energy negotiations other than buying time.

NS2 checkmates Denmark

With the new border with Poland in place, the Baltic Pipe was soon approved in Denmark. And as a final step, Denmark saw new opportunities arising for Nord Stream 2. In early 2019 the Danish Energy Agency asked NS2 to look at a third route through the newly acquired EEZ south of Bornholm. With three routes now in play, everyone held their breath. One route would go through Denmark’s territorial waters, two through the EEZ. One could be blocked by Denmark; the other two could only be blocked if the environmental and economic risks were too great.

The country was left alone as the forward post for months due to the lack of a clear strategy and solid alliances on energy issues

The final round for Denmark started on 28 June 2019. NS2 strategically withdrew the application through Danish territorial waters and effectively checkmated Denmark. Putin chipped in during an energy conference in Moscow in October: ‘Denmark is a small country which has come under strong pressure, and it is up to it whether or not to assert its independence and show it has sovereignty.’ Otherwise, there would be ‘other routes’, he added. On 30 October 2019, NS2 had the third route approved, enabling it to start construction in the Danish EEZ. Denmark was out of the spotlight. Two months later, the US imposed sanctions on NS2 and stopped the construction.

All in all, Denmark was largely caught unprepared in this story of gas geopolitics. With no clear strategy for energy geopolitics, the Danish authorities had to play things by ear while facing immense pressure from the US, Germany and Russia on opposing sides of the dispute. The EU was divided on the issue, as was NATO. The Centre of Excellence on Energy Security in Vilnius could have provided informal guidance on how to tackle energy geopolitics along the way, but Denmark is not represented there. The US only stepped in after Denmark had been ‘singularized’ and left exposed for two years. Going forward, Denmark risks facing diplomatic payback from Poland and Russia in future negotiations.

The lesson to be learned is that small countries like Denmark need to increase their competencies and build alliances on international energy security issues because energy is increasingly becoming part of the geopolitical landscape.

DIIS Experts