Re-integration efforts must put vulnerabilities at the centre

Every year, several hundred thousand migrants return to Ethiopia, where they struggle to integrate back into society. They must deal with the traumatic events of their journeys while also facing social stigma and exclusion.

■ Sexual violence and abuse are widespread among Ethiopian male migrants yet taboo, and psychosocial support should address the vulnerabilities of men

■ Livelihood interventions should address the problem of social stigma

■ Re-integration is difficult as social positions and relationships will never be as they were before migration

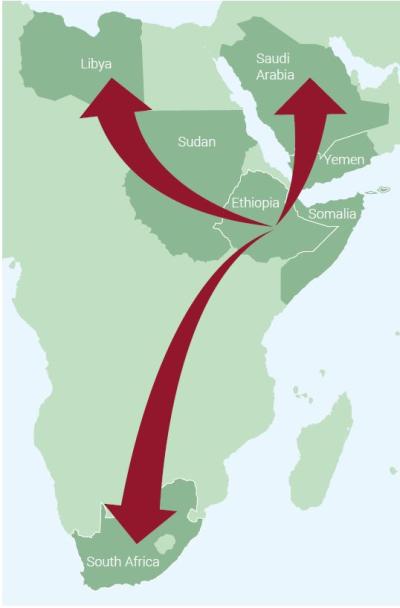

Ethiopian migrants leave their homeland in the hope of employment and better livelihoods abroad, or to escape local conflicts that have resulted in millions of internally displaced persons. They often resort to irregular routes to circumvent the strict regulations on regular migration. More than 1.5 million Ethiopians live abroad, many under precarious conditions, hiding from the local authorities, and constantly facing the risks of deportation.

Since 2017 more than 350,000 Ethiopian migrants have been deported from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, most of them men. Many others have been assisted to return home through voluntary return and re-integration programmes by the EU, IOM and others.

Upon their return, they face the difficult task of re-integrating back into the society they left, balancing social stigma from their local communities with personal challenges arising from the traumatic events they experienced during their migratory journeys.

Abuse and violence

Ethiopian migrants, especially men who have very few possibilities of regular migration, usually undertake perilous journeys on foot or using land transport likefreight trains, traffickers’ lorries etc. All the available routes are highly dangerous. Some only lead to precarious forms of employment in transit, whereas others are extremely dangerous in themselves.

Most of these migrants are facilitated by brokers or smugglers, who often approach them offering ‘free’ guidance before eventually taking control of them. The brokers typically manage a jurisdiction or a territory, each broker demanding a fresh sum for every new part of the route, as well as attempting to increase the flow of migrants and thus benefiting from economies of scale.

Throughout their complex journeys, migrants are faced with a variety of stressors, including hunger, thirst, labour exploitation, sleep deprivation, denial of salaries and different forms of emotional, sexual and physical abuse.

Many Ethiopian men re-migrate from the belief that they would rather risk death during their journeys than return to a perceived situation of worthlessness.

All these challenges are strongly associated with the mental health conditions of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and somatization. Of the more than 12,000 returnees from Saudi Arabia seen by MédecinsSans Frontières for mental health problems, 96 percent reported having witnessed violence or abuse during their journeys.

We cannot consider the process of returning or reintegration without understanding the violent and traumatic journeys that most Ethiopian migrants go through and their ultimate impact. Abuse, rape, violence, murder, torture and the possibility of death from thirst, hunger or heat leave immense psychological and emotional scars. Such traumatic events take place not least in the big halls in the transit countries that migrants describe as “Megazens”, literally warehouses where brokers keep migrants and torture them for ransoms before allowing them to continue their journeys.

Despite being an everyday reality for many of these male migrants, perpetrated by employers, smugglers, brokers or local groups, sexual violence is considered a taboo subject among Ethiopian migrants. As a result, male Ethiopians who are survivors of sexual exploitation and abuse usually hide their experiences out of a fear of social stigma. Often they neither pursue formal health care support nor report the crimes committed against them, since any contact with the local authorities is likely to result in imprisonment and/or deportation. This merely strengthens the stereotypes associated with homosexuality among Ethiopians and increases the fear of potential ostracism, leading to continual efforts to hide such crimes even from one’s family and friends.

Male vulnerabilities

While the aggravated vulnerabilities of women and child migrants are appropriately recognized and addressed, the vulnerabilities of men are sometimes overlooked from misunderstood assumptions that they have greater resilience in the face of such events and experiences. However, Ethiopian male migrantsare often very young men, and they are deeply affected by the stressors of their journeys, perhaps aggravated by a willingness to take greater risks. The result is that reintegration and psychosocial well-being may pose special challenges to their identities and masculinities.

Migration journeys may be seen as rites of passage, both in themselves and through household expecta-tions that boys will return as men and breadwinners, able to feed their families through newfound skills and capital. However, when migration efforts fail or attempts to save up funds are unsuccessful, perhaps leading to a forced return, these masculine ideals are challenged. Migrants’ masculinity is undermined or misperceived by families and communities, causing even greater difficulties for them.

As a result, their social status must be renegotiated and struggled over as part of the process of attempting to find their place again in their families and communities. However, when hopes of upward social mobility fail, this challenges their masculine statuses and identities, which are tied to social norms. Social norms of manhood (wendinet) in Ethiopia mean it is difficult if not impossible for the migrants to discuss and address such issues openly, even among close friends.

Psychosocial support

Reintegration programmes often maintain a focus on economic reintegration and employment for the very good reason that a lack of livelihood opportunities is an important driver of migration in the first place. Yet the creation of future livelihoods and employment depends on returnees’ psychosocial well-being, something to which existing reintegration program-mes and policies often do not give much importance. Problems with psychosocial well-being emphasize how deeply the instrumental and mental dimensions of migrant life intersect with and complement each other.

The inability to provide financially for one’s family leads to frustration, while social concerns over declining family care, peer pressure and pressure from families or community misconceptions can lead to social isolation. Combined with the inability to take up employment, this forms a problematic cycle of perpetual aggravation. The stigma and blame from families because of their unfulfilled expectations of the migrant often lead to a failure of support and reassurance. As a result, many Ethiopian men choose to migrate again, preferring to risk death during their journey rather than return to a situation of worthlessness, distress and social stigma.

Main routes

Psychosocial challenges make it difficult either to obtain or to maintain employment, greatly shaping the prospects for re-integration, and likely feeding the individual’s drive to re-migrate. Without paying attention to psychosocial well-being through consultation and treatment by experienced professionals, employment and future livelihood programmes are unlikely to be effective.

Rethinking re-integration

Return journeys and the process of reintegration are too often thought of as forming the opposite of arduous and challenging outgoing migration efforts. But return migration is never an easy task, neither when it is a matter of assuming old roles and relationships, nor when it comes to becomingsomeone new. In fact, the process of returning and facing reintegration may be every bit as tough as leaving one’s place of origin in the first place.

There is a close connection between the events of the journey and the ability to reintegrate. Reintegration support is crucially important, yet the process of reintegration cannot be determined only by the level of services of livelihood support provided for the migrant upon return.

While it is programmatically logical to assume a difference between outward migration, return migration and re-integration, there is no separation of ‘during’ and ‘after’ when it comes to migration. The traumatic events of irregular migration are not a temporary process or journey, but rather an enduring process of personal, mental and existential change, since all migratory efforts have strong life-changing aspects.

The life-changing effects of migration for these Ethiopian men are seldom for the better, which means that what was before will never be again. There are no developments, treatments or employment that can bring back how things were. This puts the very notion of re-integration into question.

Therefore the objective can never be to re-instate migrants ‘back’ into their communities with an expectation that they can reassume social relationships or positions similar to what they had before. Instead, re-integration interventions should start out from a recognition that all Ethiopian return migrants have witnessed or experienced violence and trauma and should work with the aim of providing adequate and effective services based on differentiated needs.

This Policy Brief is based on findings in the DIIS Report, ‘“No place for me here”: the challenges of Ethiopian male return migrants’.

DIIS Experts