Internally displaced people in Mali's capital city

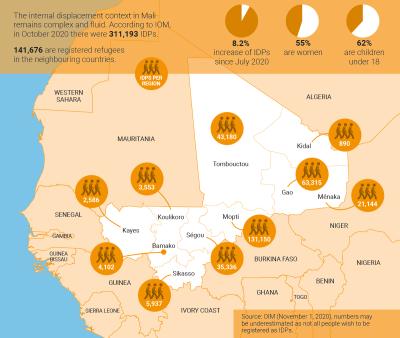

As world attention focuses on Central Mali’s conflict hot spots, more than 50,000 of the country’s 311,193 internally displaced persons (IDPs) have fled to Mali’s southern cities, including the capital Bamako. The inhuman conditions in the informal IDP camps manifest an overall failure to protect civilians despite the presence of more than 25,000 foreign soldiers, 13,000 of whom are UN peace keepers. To support peacekeeping efforts, long-term development investment must be complemented with short-term assistance to provide protection, food and shelter to Mali’s most vulnerable victims of war.

■ Mali needs to develop and implement a national strategy that respects the rights of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to make free, informed and voluntary choices of settlement.

■ Long-term development assistance must be complemented with flexible, immediate and short-term assistance to the most vulnerable IDPs.

■ Access to accommodation, jobs and health facilities is needed to avoid precarious survival strategies, such as street begging, child marriage and survival sex.

After close to eight years of French military and UN stabilisation engagements in Mali, peace is far from returning. Indeed, since 2015 as jihadist groups have spread from the northern regions to the central region of Mopti, the country has only plunged into further despair as the security forces, jihadist groups (al Qaeda and Islamic State) and self-defence militias have escalated the violence. Civilians are suffering from unremitting acts of atrocity: relatives are murdered and kidnapped, goods are stolen and armed groups torch houses and lay entire villages to waste.

Despite the great humanitarian needs, the space for humanitarian action is shrinking. Violent attacks against humanitarian workers are increasing and reaching civilians in danger is difficult due to the presence of armed groups. The government is attempting to respond to the unsolved issue of supporting IDPs through various multidimensional development plans and by following the measures of the 2015 Algiers Peace Agreement, but the humanitarian question is largely seen as secondary to defence, security and political priorities.

In the face of the intensity of attacks and violence by armed groups in central Mali, more than 50,000 IDPs have sought refuge in the south of the country and, increasingly, in Bamako since 2018. Here, IDPs gradually blend in with the urban poor as their living conditions continue to deteriorate.

Bamako: stuck between displacement and return

The IDPs do not consider Bamako their destination. The majority intend to return home once security and socioeconomic conditions improve, but ongoing insecurity, an unstable food supply and poor living conditions continue to make return impossible and displacement is becoming protracted. In the meantime, the city offers few opportunities and many risks. The inhuman conditions at the Faladié camp illustrate the precariousness of life as an IDP in Bamako.

We live in misery here. We do not have enough to eat, and we are completely dependent on help from others to survive, but often we are queuing for six hours without receiving anything

(woman at Faladié)

Seeking shelter at Faladié

Located in commune VI of Bamako District, just five kilometres from the headquarters of MINUSMA, the United Nation’s mission in Mali, the livestock market in Faladié shelters approximately 800 IDPs, mainly from the centre and north of the country. The situation in the camp exemplifies the reality of many internally displaced in Mali.

The first IDPs arriving with the outbreak of the war in 2012 were relatives of the livestock traders in charge of managing the site. Many others have followed since. Most of the newly arrived have relatives or fellow villagers already at Faladié. Although the municipality has accepted the presence of IDPs at Faladié, the Malian state cannot authorise anyone to settle there because (according to the social development officer in charge of IDPs) the land is owned by a transnational airport agency called ASECNA (Agency for the Safety of Air Navigation in Africa and Madagascar).

The Faladié camp resembles a waste dump.

The makeshift tents constructed using plastic bags and scraps of fabric stand alongside piles of garbage. When the wind catches the smoke from burning waste and blows it straight into the tents, it stings the throats of the people who live there and exacerbates the risk of diseases such as tuberculosis. Space is limited. Children and adults are suffering from malnutrition and untreated war trauma. There is a lack of clean water, and only a few can afford the pennies it costs to use the ramshackle communal toilet. The others are forced to use the open piles of refuse lying around. The camp is a perfect breeding ground for coronavirus.

Why do they give us soap to wash our hands, when we have nothing to eat? (elderly man at Faladié)

Do it yourself aid

In 2018, following a wave of further atrocities in Central Mali, a local NGO started distributing food aid at Faladié. A mixture of local and international NGOs and benevolent individuals have been distributing food, clothing, money and health services since. The aid distribution is managed by a committee made up of Faladié’s traditional livestock traders in an ad hoc manner. Established international humanitarian organisations have no presence. The inhabitants are very appreciative of the help they receive. However, several of the interviewed IDPs mentioned discrimination, favouritism and corruption within the aid distribution system. The weaknesses of the system include: unequal aid distribution, mismanagement, lack of transparency, lack of coordination between actors on the site, absence of basic needs assessments and insufficient aid. The IDPs feel entirely neglected by the national authorities.

A destructive fire

On the night of April 28, 2020 a major fire at Faladié destroyed most of the IDPs’ belongings and killed the little livestock they had. Many IDPs were relocated to a nearby school at Mabilé, about five kilometres distant, which the government opened in May 2019 to support IDPs. Until the fire only 67 households had been staying at Mabilé. After the fire several international organisations intervened to provide immediate support to the survivors. At Faladié, UNHCR only distributed some basic emergency shelters and Non-Food Items (NFI). Nevertheless, most of the IDPs chose to stay in or return to Faladié as they found the conditions at Mabilé unliveable. Several expressed that they did not want sleep together with other people in the same room without privacy. Others said they could not adapt their way of life to the Mabilé centre and that they did not want to be displaced again. At Faladié many now sleep without shelter on the burnt-out site, under the risk of being evicted. Despite the inhuman conditions, most of the IDPs preferred to stay at Faladié because of the economic and social opportunities the camp offers.

Survival strategies

Since before the 2012 security crisis the livestock market at Faladié has been run by livestock traders who profited from renting out parcels of land for cheap accommodation to Bamako’s seasonal street beggars – a survival strategy that has been picked up by many IDPs. Most of the men go to the city centre to beg and look for jobs. ‘Faladié is closer to the city, access to the market is easier’ explained one young man. Others engage in small income-generating activities such as purchase and resale of animal feed, cattle fattening and petty trade. The female-headed households, which make up more than 50% of the IDPs, are at risk of resorting to child marriage, survival sex and other precarious coping mechanisms to survive.

The IDPs at Faladié are aware of COVID-19 through various information channels (radio, television, health campaigns) and the local authorities have distributed protection kits (masks, soap and hand sanitiser). But the IDPs express more urgent problems: namely the ongoing war, and what they refer to as ‘the hunger virus’. Some believe that COVID-19 is an invention to enrich politicians, others that it is only relevant to rich people. Thus, they do not feel concerned by the virus, and have not engaged in implementing the government’s prevention measures.

Perspectives

The IDPs in Bamako hope to return to their places of origin and continue their previous livelihoods. However, until peace is restored and without further assistance, the Faladié residents have no viable survival strategies. Having lost all their belongings, they live in extreme poverty.

The government fears that informal camp sites like Faladié become permanent, which could attract more IDPs. However, despite having ratified the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of IDPs (the Kampala Convention) in 2012, the government still lacks a policy for how to protect the rights of IDPs to make informed, free and voluntary choices of settlement. Such a policy would enable the international humanitarian actors to support the IDPs in a flexible manner.

The international humanitarian organisations have the capacity to assist IDPs in Bamako, but they need a formal request from the government to do so. Unless short, medium, and long-term solutions are found to support the IDPs, both in conflict-affected regions and in the southern cities (including Bamako), IDPs will continue to present a humanitarian challenge in Mali for generations to come. Men, women and children will continue to embark on futureless survival strategies unless the steps necessary to improve their situation are taken. If the political, security and economic situation in Mali deteriorates further, large and disenfranchised groups of IDPs are likely to remain a source of long-lasting fragmentation and instability in the entire region.

This policy brief is commissioned by Danish Red Cross. The authors are grateful to Aboubacar Diarra for assisting the fieldwork.

DIIS Experts