Germany’s approach to Baltic Sea security

Although Germany is taking on more responsibility in the Baltic Sea region, the world is changing faster than Germany is changing its approach. The country’s policies accordingly lack strategic direction and vision – and above all, action.

■ Germany is increasingly taking more responsibility for security in the Baltic Sea region.

■ Its focus has been and remains on multilateral initiatives within a NATO and/or EU framework, which is very welcomed by the states in the region.

■ However, the changes Germany is making are being outpaced by the changing international context. The country is doing more, but not yet enough: concrete action is needed with respect to the Bundeswehr, decision-making procedures and strategic culture.

If one wants to understand the German approach to security in the Baltic Sea, the context of Russo- German relations is crucial. Making the headlines once more with the poisoning of Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny in August 2020, for a moment it seemed as if ‘a turning point’ in the relationship between the two countries had occurred. Even the future of the highly controversial Nord Stream II gas pipeline was hanging in the balance, as reflected in the German foreign minister, Heiko Maas, telling a German tabloid, ‘I hope the Russians don’t force us to change our position on Nord Stream 2’. But rather than a turning point, it seems that Navalny’s poisoning is just an additional step in the deterioration in relations between Germany and Russia.

A special relationship that is not so special anymore

After German reunification in the early 1990s, Germany attempted to balance Russia and western Europe. Advocating rapprochement with Russia while pushing for the integration of its eastern neighbours into Europe, under Merkel’s first two coalition governments (2005-2013), Germany oscillated between wanting to strengthen the partnership with Russia and supporting its EU neighbours to the east. Since the Ukraine crisis of 2014, however, Berlin has paid much more attention to Russia’s actions and threats to the Baltic and east European states, growing increasingly frustrated with Russia’s aggressive and assertive actions, such as hacking, election meddling, spreading disinformation, political assassinations and Moscow’s uncompromising attitude in Syria, the Donbas and Belarus. This has led to a slow realization among Germany’s political elite that rapprochement on the basis of shared values and reliance on a rules-based international order is anything but possible. Nevertheless, Germany still does not perceive Russia as a direct threat, unlike its eastern neighbors.

Germany’s challenged leadership in the Baltic Sea region

This increasing frustration is reflected in Germany’s approach to security in the Baltic Sea region (BSR), which has seen increasingly assertive posturing by Russia, a build-up of forces and increases in grey-zone conflicts in form of disinformation, cyber attacks and other destabilization operations. As a consequence of the Ukraine crisis in 2014 and in response to Russia’s assertive posturing, NATO has stepped up its presence in eastern Europe to strengthen its deterrence and defence posture on its eastern borders.

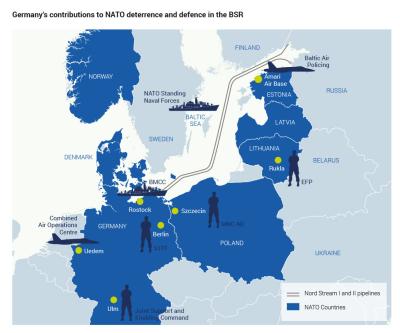

Germany has taken a leading role in strengthening NATO’s eastern flank, clearly taking on more responsibility. Very much in line with the country’s general approach to international politics and the international order, the German approach to the Baltic Sea clearly and explicitly focuses on multilateralism, in which it joins initiatives within a NATO or EU frame- work, or together with several other countries. The maritime domain is of particular interest to Germany, as homeland defence and the defence of its allies closely overlap in the Baltic Sea.

Yet, despite the many German initiatives and their relative success, numerous issues continue to plague the German approach to Baltic Sea security. Historically, Germany itself was perceived as a threat by other states in the BSR. However, given Germany’s continued commitment to the security of the Baltic States, as well as its economic investments and procurement projects designed to strengthen the partnership between the Baltic States and Germany, this perception of the latter is slowly changing. Germany’s insistence on multilateral approaches to security also contributes to the creation of a more positive view of Germany as one of the main security providers in the region.

Despite the increase in defence spending, the German armed forces continue to be plagued by low levels of readiness, aging and limited equipment, and procurement problems.

Nonetheless the highly controversial Nord Stream II pipeline project mentioned earlier is causing major problems for Germany with its eastern and northern neighbours, as well as with important allies within NATO, such as the US. These countries oppose the project because they fear increasing European dependence on Russian gas, as well as the potential exertion of Russian political and economic influence on traditional transit countries in eastern Europe, where Russia can threaten their gas supply without affecting the supply to western Europe through the new pipeline. The US has even introduced sanctions on businesses involved in constructing the pipeline. Germany, however, has maintained the argument that the pipeline is a purely economic project quite separate from security policy. While debate on the future of the pipeline was revived in the wake of the Navalny poisoning, it quickly became clear that the pipeline project, which is almost complete, will be finished regardless, and that the damage to Germany’s ties with its allies and neighbours will linger, as is visible, for example, in Germany’s relationship with Poland, which has deteriorated substantially in recent years.

Ground

-

Leads NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) multinational battlegroup in Lithuania.

-

Enlarged presence at Multinational Corps North- east (MNC-NE) Headquarters (the High-Readiness Force Headquarters) in Szczecin, Poland (set up by Germany, Denmark and Poland in 1999).

-

Contributed to creation of NATO’s spearhead force (the Very High Readiness Joint Task Force, VJTF). Germany last had a leadership role in 2019, involving around 10,000 troops, and will do so again in 2023.

-

Set up new NATO headquarters, the Joint Support and Enabling Command, in Ulm, Germany, focused on ensuring troop and equipment movements across internal European borders.

Sea

-

In the process of creating a multinational ‘Baltic Maritime Component Command’ (BMCC) at the German Maritime Forces Staff in Rostock, under German leadership. Serves as a NATO command, but can also be used outside NATO.

-

Contributes regularly to the NATO Standing Naval Forces of the North (Standing NATO Maritime Group One and Standing NATO Mine Counter Meas- ures Group One).

-

Created the annual Baltic Commanders Conference in 2015.

Air

-

Contributes regularly and extensively to Air Policing of the Baltic states, controlled from the NATO Combined Air Operations Centre at Uedem, Germany, which also coordinates recurring NATO exercises in the Baltic States (e.g. Baltic Operations (BALTOPS) and Ramstein Alloy).

Big questions...

Germany’s role in BSR security also highlights the big questions: in order to take on more responsibility, Germany has significantly increased its defence spending since 2014, spending $49.3 billion in 2019, a 10 percent increase from 2018. Yet, Germany is still falling short of the 2 percent of GDP threshold reaffirmed at the NATO Wales summit in 2014, spending only 1.36 percent in 2019 and 1.57 percent in 2020 (this reflects a lower GDP in 2020 due to COVID-19, which at least partially explains the rise in the percentage). While there is widespread agreement in Berlin that Germany and Europe need to do more on defence, with German political leaders stressing the importance of multilateralism and complementarity with NATO, allies accuse Germany of not meeting its ambitious rhetoric with proper action or concrete steps: the failure to reach the 2% goal is often seen as reflecting a lack of alliance solidarity on Germany’s part, as is Germany’s preference for stabilization, training and support missions over combat operations.

Despite the increase in defence spending, the German armed forces continue to be plagued by low levels of readiness, aging and limited equipment, and procurement problems. A major overhaul of the Bundeswehr is considered crucial, but according to recent reports by the German Ministry of Defence and the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces, this has yet to take place. The problems of the Bundeswehr are so serious that a recent report by the Munich Security Conference (MSC) concludes that ‘[w]ithout eliminating these gaps, Germany will not be able to contribute to the thoroughly ambitious capabilities to NATO that Berlin has long since promised’ (Zeitenwende, p. 89). While reforms to the Bundeswehr are planned, they are not adequately represented in Berlin’s budget plans.

Not only does the Bundeswehr need updating, so do Berlin’s institutional arrangements and decision- making procedures. The complexity of today’s security issues requires inter-ministerial cooperation going beyond what Germany currently has. An institution for strategic debates, prioritization and coordination is crucially lacking, according to Julianne Smith in the Süddeutsche Zeitung (‘Denk’ ich an Deutschland’, 13 February 2019). Last year, a situation room for foreign and security policy was set up at the Foreign Office in which the Chancellery and foreign, defence and interior ministries participate, but giving a larger role for the Federal Security Council (Bundessicherheitsrat) would also involve other important ministries, such as justice, finance and development, and thus enhance coordination. Finally, the MSC report also calls for the development of a national strategic culture if Germany is to fulfil its international responsibilities, with regular publication of a national strategy document, as well as awareness-raising public debates about German security and defence policy, strategy and priorities.

The German approach to security in the BSR thus very much reflects the broader global shifts to which Germany needs to adapt. Germany has been crucial in maintaining dialogue with Russia because of its special relationship with the latter, but the lack of agreement with its allies over the relationship with Russia and the absence of a coherent strategy on security and defence policy within Germany are highly problematic, reducing security in the BSR. While Germany is taking on more responsibility, adjusting its approach to security and defence to the changing situation, more will be necessary if Germany is to be able to provide security for its citizens and allies. Fundamental adjustments to Berlin’s foreign, security and defence policy are necessary, first and foremost updating the Bundeswehr and decision-making procedures, as well as encouraging a public debate about Germany’s security and defence policy and its strategic direction within Europe and NATO.

This policy brief is based on a closed round table organized by the author in autumn 2020 and conversations with experts and officials.

Amelie Theussen is assistant professor at the Center for War Studies, University of Southern Denmark (amelie@sam.sdu.dk)