COVID-19 in Mozambique

The first case of COVID-19 was discovered in Mozambique on 14 March in the country’s capital, Maputo, and soon afterwards the city’s mayor and his wife also tested positive, after the mayor returned from a trip to the UK.

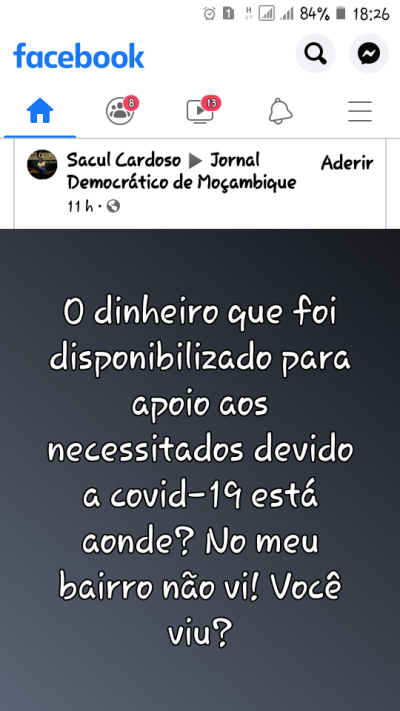

The positive test could have created sympathy for Mozambique’s leadership, but that has not proved to be the case. In fact, the opposite has happened. As in many other African countries, coronavirus has not exactly led people to rally around their leadership but instead has demonstrated the low trust that already exists in the government.

One person on social media wrote:

"We never saw the people who were sick because all of this is false, and the government only spreads [the idea of] the virus to get the help of [USD] 700 million [requested from international development partners], just to benefit the country’s leaders".

For a Danish version: Read Globalnyts version: https://globalnyt.dk/content/covid-19-i-mozambique-politivold-mistillid-til-regeringen-og-frygt-sult

Rumours spread that it was only the rich and white people who could contract COVID-19, along with the Chinese. When the President travelled to Harare, the capital of neighbouring Zimbabwe, in May, essentially breaking the travel ban imposed under his own state of emergency, criticism and disbelief in the government grew.

Fear the disease, fear the police

People in Mozambique do not just fear the virus, however; they also fear hunger and police violence as consequences of the lockdown the government has imposed. The state of emergency is having severe repercussions for many people’s social lives and even their day-to-day survival. For many, to ‘stay at home’ means not being able to feed themselves and their families; in this context, violations of the restrictions can be a matter of survival. So far, the government has not provided any material support to compensate for people’s loss of incomes. Instead, the police are arresting and physically punishing those who attempt to circumvent the lockdown restrictions. The most economically vulnerable face a tough choice between survival and being the victims of harsh police actions.

Indeed, the lockdown has led to a rash of police arrests in Mozambique’s towns and cities. Street vendors, young men drinking in public spaces and others gathering in groups, as well as those who are not wearing masks, are especially the targets of arrests. Police responses to violations of the lockdown are harsh and violent: ‘People are taken to the police cell and then they are beaten [chamboceado], just for not wearing a mask’, said one interviewee from Tete.

The number of persons who have tested positive in Mozambique has gradually risen to 859 by 28 June, and so far there have been five deaths. The first cases were concentrated in Maputo and at a gas-industry construction site in Cabo Delgado owned by Total, but now there are cases of COVID-19 across the country.

On 30 March, the President declared a state of emergency and imposed a partial lockdown that has now been extended to the end of July. As in many other countries, the state of emergency meant that schools and many other public institutions were closed, freedom of movement was restricted, a maximum of twenty persons and social distancing of 1.5 metres were imposed on gatherings, restaurants, bars and smaller drinking places (baracas) were closed, along with churches, sports and other social activities, wearing masks was made mandatory, and street vending was prohibited. The government has provided civic education on how to prevent the spread of the virus with a focus on hygiene and social distancing, recommending that people ‘stay at home’ (fica em casa).

Arguably, at the time of writing the confirmed number of persons infected with COVID-19 in Mozambique is not high compared to many other countries in the world. As in the rest of the southern African region, the rate of infection has not exploded as initially predicted by WHO, despite its warning in April that Africa could be the next epicentre and that its already fragile health systems would collapse. Although this has not happened, the infection rate is growing in Mozambique, and there are likely to be many uncertain figures for the extent of the pandemic, as testing capacities are extremely low: by 28 June, only 28,586 persons out of a population of 31 million had been tested. The fear of contracting the virus is also growing. As a man in the city of Tete expressed it:

"Like others I’m afraid of being infected with the virus, I’m afraid of traveling, and I’m afraid of being close to other people".

The fear of hunger and mistrust in government

The far-reaching dilemmas created by the coronavirus crisis in Mozambique are being played out in a context in which most of the population already live in poverty and are occupied in the informal economy, thus depending on earning a daily income, with no secure employment contracts or safety nets. Many people are still struggling to recover from last year’s Cyclone Idai, one of the worst tropical cyclones ever recorded in Africa, while in the northern province of Cabo Delgado people are being displaced from their homes due to the intensification of the armed insurgency. These hardships overlap with a high level of mistrust in the government fuelled by a long legacy of corruption, unequal development and the routine use of state violence against delinquency and disloyalty.

In many ways, the corona crisis is exposing and intensifying an already existing political and economic crisis in Mozambique, intensifying continuities that now co-exist with new fears, uncertainties and mixed information about the nature of the virus itself, which also feed suspicion and discrimination against those who have contracted it.

In early June, the Minister of Labour and Social Security announced that at least 39,000 people had lost their jobs in the formal sector due to COVID-19, but the number is very likely to be much higher in the informal sector.

Especially hard hit are street vendors, small business owners and people on temporary and informal contracts. Also suffering are those who depend on remittances from relatives, mostly informal migrants in neighbouring countries like South Africa, who have now been sent home. Among these vulnerable groups, which account for a very large part of the Mozambican population, there is a real fear that people will die of hunger due to the lockdown, a fear that is as high or perhaps higher than the fear of dying from the virus. A few weeks or even days of lockdown can mean all the difference between poverty and starvation.

A regional problem of poverty

This view is echoed elsewhere in the region, as in neighbouring South Africa, where critical voices have warned that the lockdown itself will cost more lives than the virus due to losses of jobs and incomes. Lockdowns are tough for the economy everywhere in the world, but they have especially severe repercussions in poverty-stricken countries like Mozambique, where the state’s capacity and willingness to provide financial support to those affected is very low.

As Alex de Waal and Paul Richards wrote in a recent article, lockdowns in poor African countries will only work if substantial emergency assistance is provided by the international community. Already on 23March the Mozambican government made a request to its development partners for USD 700 million to cover the fiscal hole in the 2020 state budget caused by the pandemic, as well as to finance the fight against the disease and provide support to the poorest. A little less than half this amount has been granted in credit by the IMF, and other donors, like the EU, have also mobilized COVID-19-related aid to Mozambique. So far, the government has used these funds to reduce the costs of fuel and electricity, lift the taxes on sugar, oil and soap, and strengthen the health sector. But it has not provided any food distribution or compensation packages to those affected, as has happened, for instance, in neighbouring South Africa.

The government is not giving us any help. Now they [the government] are only asking for external help and waiting for the donors of other countries so they can rob [the donations]. Unfortunately, we do not have a serious government that is concerned with the population. They are corrupt

The lack of government support is fuelling frustration in a population that is already deeply sceptical of the government. Few trust that the government will provide the necessary material support or that it will necessarily act in the interests of the general population. Many fear that whatever international aid is coming in will be used to fill the pockets of the governing elites. Reflecting this view, a resident interviewed in Chimoio – actually a state functionary himself – said:

As this quote shows, distrust of the government is informed by a long legacy of corruption and recent experiences of the misuse of international loans and aid, most recently during Cyclone Idai in 2019, when large amounts of aid never reached the intended victims. The tattered image of the Frelimo-led government, which has held on to power since independence in 1975, partly through the alleged rigging of elections and partly through the violent crushing of its critics and opponents, has also shaped people’s views of the corona pandemic. In fact, at the beginning of the lockdown many disbelieved the reality of the virus itself and its alleged spread in Mozambique, not wishing to trust the government’s warnings and information. Some even claimed in the media, including a former Minister of Health and public health specialist, that the government was deliberately inflating the diagnosed data for the spread of COVID19 to enrich itself from international funds.

To be fed by the government, this is impossible. All they [government] can do is to order people to stay home, and then they spread out the police to all corners so they can punish the people

Although some people still doubt the veracity of the threat from the virus, many changed their minds as the numbers of those infected increased and the first person died from COVID-19, a thirteen-year-old girl from Nampula. When COVID-19-positive cases began to appear in Tete and Chimoio, as well as other provincial towns, it sparked increased acknowledgement of the virus. It also intensified the enforcement of the lockdown by the state’s security forces.

The police presence in public spaces has grown enormously, and with it police violence has increased. In the absence of government care, the excessive police enforcement is creating further distrust between the state and its citizens. Reflecting on the current lockdown, a female interviewee from Chimoio said: "To be fed by the government, this is impossible. All they [government] can do is to order people to stay home, and then they spread out the police to all corners so they can punish the people".

Police violence grows

Compared to a normal pre-lockdown day, the streets of provincial cities like Tete and Chimoio are largely deserted, except for a heavy and continuous police presence. ‘Not five minutes go by without seeing the police. They are checking everyone’, said one interviewee in Tete. Police vehicles and heavily armed officers on foot patrol day and night. They enter shops, market places, banks and other venues for smaller social gatherings and drinking stalls, and check trucks, buses and cars coming from other provinces and neighbouring countries.

As in many other countries, the police in Mozambique have been employed to enforce the lockdown and to ensure compliance with it rigorously in the name of protecting people from coronavirus. But how the police perform this task varies a great deal across the world, reflecting differences in existing policing cultures and in the character of the political regimes they serve. In Mozambique, as in other countries in the region, the police are already known for using excessive force and extortion while carrying out their function of law enforcement.

The current situation is no exception. In fact, cases of police brutality against citizens during enforcements of lockdowns have risen, exemplified by the massive arrests, beatings and even killings of citizens by police forces. In South Africa alone, 230,000 lockdown-related arrests had been made by the end of May, and eleven citizens had lost their lives due to police actions. Kenya’s slum areas have also experienced high levels of police brutality in enforcing the coronavirus curfew, while in Nigeria it was reported in late April that the number of those killed by the security forces exceeded the number of patients who had died from coronavirus in the country. While some human rights organisations and media channels have reported on this surge in coronavirus-related police violence in African countries, it has arguably not received the same international attention as the recent police killing of George Floyd in the US. In the case of Mozambique, it is an issue that has largely been silenced, despite the fact that the threat and fear of arrest and violence by the police are affecting the everyday lives of many of the country’s citizens in the current situation.

Most of those who are arrested for violating the lockdown do not pay official fines, nor are they prosecuted officially in court. Instead, they are beaten and put in a cell at a police station. Release usually depends on paying off the police. It is unclear whether all arrests are reported officially, but in April alone the police stated that 869 persons had been arrested due to the lockdown.

Some arrestees are set free from the police cell after a day or so, but there are also examples of longer confinement. In one case from Tete, for instance, a taxi-driver who was not wearing a mask was stopped by the police, arrested and spent five days in a cell until he was released after his family had collected the money to ‘buy off the police’. If they had not paid, he was told, he would have stayed in the cell for thirty days for ‘disobedience’. The police have also arrested numerous persons caught drinking in public or behind drinking stalls, and mass arrests of street vendors have been observed. People have also been arrested for saying communal prayers with their pastor in private homes.

Since the first extension of the state of emergency was announced by the President on 28 May, when the President also encouraged the police to take extra strong measures against disobedience, the police have also been implementing a non-official curfew in some cities and towns. Typically, they enforce a curfew between 22.00 and 07.00, arresting anyone walking the streets who cannot convince the police that they have important business to attend to. The curfew is not an official part of the state of emergency rules, but the police’s way of interpreting their role of enforcing the lockdown and implementing the President’s call to ‘stay at home’. More people without masks have also been physically punished and incarcerated for 24 hours since the extension.

There have also been incidents of police violence being committed in public spaces. In Tete, for instance, the police beat five young men in public who were caught drinking behind a small drinking stall. One of the men was severely injured, and all five were put in a police cell. In Beira one person was beaten to death by the police in the street for disobeying the lockdown.

Numerous citizens have also complained that some police officers are using the lockdown situation to extort money and goods from citizens, essentially to line their own pockets. This is happening on streets and at market places. A market vendor in Tete, for instance, recalled that she had been forced to pay off the police to be able to continue selling her goods. They came to her market stall and threatened to take her to the station on the grounds that she was violating the lockdown. When she complained, saying that she needed to sell her goods to survive, they asked her to pay them money. After she paid, she was allowed to go on selling.

At the beginning of the lockdown period, some people were happy about the increased police presence, believing that it would help reduce the spread of COVID-19. There were also incidents of citizens reporting those who were not observing the lockdown to the police. Some interviewees also commented that the police’s strong presence had reduced ordinary crime significantly in their neighbourhoods, creating a sense of increased security. But given how violently the police are handling the situation, opinions are changing. Popular criticisms of police actions are mounting, as people are increasingly afraid of police actions. Insecurity is now associated not with criminals, but with police violence.

The government can reintroduce the chamboco (beating stick) but it is of no use because hunger will spread, and no one can resist

It is evident that some Mozambicans are disobeying the lockdown because they do not believe that the virus is a real threat to Mozambique. But disobeying the lockdown is mostly a matter of survival. The absence of government care is forcing many people to continue their daily activities, even if it means breaking the lockdown. A commentator on social media expressed this well: ‘The ministry of health can tell us every day about the increase in infected persons, but this does not tell the population anything. The people have to eat, and that is why the minibuses (chapas) continue to be full and the markets too, and the informal vendors continue to sell on the streets. They need to survive.’ This difficult situation was vividly described by a thirty-year old street vendor in Tete:

"My job is to sell bags and stuff on the street, but now the situation is difficult because the police are prohibiting it. But to sustain my family I have to continue to risk circulating in the streets to sell, trying to avoid the police, because if they catch you, the police will take all your goods. It’s very risky, but I have no choice. I do not have a lot of money because the money I have comes from the daily sales, and if I stay at home we will not die of the virus but of hunger".

People are asking why the police are punishing people, rather than advising and helping them to protect themselves against COVID-19. The situation is increasingly becoming absurd, as expressed by a woman in Chimoio: "The government can reintroduce the chamboco (beating stick) but it is of no use because hunger will spread, and no one can resist".

State repression and police impunity

It is clear from these accounts that the police in Mozambique, as in other countries in the region, are grossly exceeding their mandate to arrest violators of the lockdown, with a disproportionate use of force even against minor infractions, like not wearing a mask. With the state acting outside the structures of the law and violating basic human rights, the state of emergency seems to be turning into a kind of state of exception. Sadly, the police’s current conduct is not unfamiliar to Mozambicans. Police violence and extortions are nothing new, but in the current situation they have become more widespread and visible, being targeted even at ordinary citizens trying to make a living.

Although since the end of its civil war in 1992 Mozambique officially changed into a liberal democracy, state violence has been a constant response to disobedience and disloyalty to the Frelimo government. The police’s current extortions also reflect the enduring problem of corruption that runs through the different tiers of government and the state apparatus. This does not mean that there are no caring police officers who abide by the principle of human rights and act in the interest of protecting ordinary Mozambicans, but the police culture as a whole is nonetheless marked by a long history, dating back to colonial rule, of the harsh and violent enforcement of public order. This culture is by and large supported by the political leadership, at least in practice, which also means that the police are rarely held accountable for excessively violent and criminal actions.

While a spokesperson for the Mozambican police force admitted to the national media in May that there might have been some ‘sporadic heavy-handedness and some instances of overzealous enforcement on the part of some police officers during the early days of the lockdown’, he also said that ‘the situation was well in hand.’ However, so far only two officers, those who had beaten a citizen to death in Beira, mentioned earlier, are being prosecuted. Other officers seem to be acting with impunity.

During this time of worldwide protests against police violence, we may ask why Mozambican citizens are not rising up against their own police. In South Africa there have been protests in recent days in solidarity with those protesting against the police killing of George Floyd in the USA, and in Kenya this solidarity has been combined with protests against COVID-19-related police killings inside Nairobi’s slums. This has not happened in Mozambique. One explanation could be that ordinary people fear that collective uprisings would be met with repressive and violent responses, as has previously happened in Mozambique. Instead, therefore, some citizens have reacted in more tacit ways.

In Chimoio, for instance, information has spread that four police officers died and three others hospitalised because market vendors had poisoned some of their food products. The police officers had previously come to the market stalls and taken the vendors’ products in exchange for allowing them to go on selling during the lockdown. Poisoning the products that the police had ‘stolen’ from them was the market vendors’ way of getting their revenge on the police and protesting against their conduct. This form of self-justice and popular counter-violence reflects a strong belief that the police and the government will not do anything against those officers who misuse their power and exceed their mandate. It also signals the deeper mistrust of the Frelimo government and the widespread erosion of justice and the rule of law in the country that people have been familiar with since long before the coronavirus crisis.

If we hear that some people here are taking in family members who are returning from South Africa, Zimbabwe or Malawi, it would be best if the community got together to expel those families because it is those people who travel back here who will make the end of us. They may have that disease, and they will spread it so that we all die

As the UN Secretary General warned in April, there is a real risk that the coronavirus crisis will also turn into a human rights crisis, as states with authoritarian pasts and fragile democracies are reinforcing harsh state measures against disobedient citizens. In Mozambique this worry has turned into a serious reality. Sadly, the culture of state violence and mistrust in the system also seem to be leaking into relations between citizens.

Discrimination and threats of popular lynching

The harsh enforcement of the lockdown is increasingly creating an uncertain and suspicious atmosphere in local communities and neighbourhoods. Among other things, this is taking the form of discrimination against those who have been infected by the virus or are suspected of being carriers. In particular, the public information that it is outsiders who have brought the virus to Mozambique has resulted in a certain bitterness and anger against foreigners and those many thousands of Mozambican labour migrants who are returning from South Africa and other neighbouring countries due to the pandemic. While quarantine is required for returnees, it is unclear whether this is being enforced or if so how, as the capacity to impose the quarantine is very low. In many cases returnees simply go and stay with members of their families. In local neighbourhoods this has led to threats to expel returnees and even their family members. A young man in Tete, for instance, said:

Health officials in Mozambique have also warned of growing discrimination against people suspected of being infected with coronavirus. In the central city of Beira and other places, infected people have been threatened with lynching. This has led to a fall in the number of people going to clinics to report flu-like systems out of a fear of letting anyone see that they might have the virus. Information has also spread on social media that two Mozambicans were lynched in Malawi after being accused of being ‘bloodsuckers of the coronavirus’. Support for such violent measures is spreading, even leading one man in Tete to assert that ‘We should use the same strategy as in North Korea, where they kill those people who are infected by coronavirus so that they do not spread it to others. In that way the virus would stop here’.

These radical ideas are far from being shared by everyone in Mozambique, but they are widespread enough for them to provoke fear among those who have been infected. For instance, a mother in Beira whose child was tested positive gave false ID information to the health authorities because she was afraid that her neighbours would discover that there was COVID-19 in their household. She fled with her child to hide from the local population but was later caught in the town of Tete, where the police returned her to Beira, where she had to enter quarantine. After quarantine she will have to face a criminal charge of giving false data to the health authorities. Other stories in the media also testify to the flight of those who have tested positive from their communities, which could increase the spread of the virus. One man in Tete explained that they flee ‘because they are afraid of dying from the virus and they are afraid of the repercussions if their neighbours discover that they have the disease. They may be lynched or beaten by the people in their community because no one wants the virus. Everyone is against them.’

Fortunately, no incidents of coronavirus-related lynching have yet been reported inside Mozambique, but the threats, rumours and fear of popular violence reflect a growing atmosphere of uncertainty and insecurity. Popular lynching already has a history in Mozambique, typically targeting criminals or people suspected of witchcraft who are caught by mobs and either beaten or burnt. People understand well that lynching can mean severe injuries and even death. So there is a good reason to flee, even if this means the virus spreading. As scholars like Carlos Serra and Bjørn Bertelsen have previously argued about the waves of lynchings in Mozambican towns in the mid-2000s, these forms of popular violence against fellow citizens should be understood as a deeper sign of frustration with a political regime that does not care for or protect its urban poor. They are signs of desperation and of distrust of the government and the state apparatus. In the current situation, these structural disparities are further compounded by great uncertainties and divided beliefs about the nature and cause of the virus itself.

Chinese warfare, God’s work and government lies

Most interviewees are quite well informed about the symptoms of the virus and can list the range of protective measures against it, like washing hands, wearing masks and keeping a social distance. But when asked what had caused the virus and how it could be eliminated, many different interpretations and opinions are expressed. People are not quite sure of what and who to believe from the excessive amount of information that is circulating on social media, in the news and in rumours passed between people.

A strong narrative at the moment is that COVID-19 is a biological weapon developed by the Chinese to kill their enemies in order to achieve global dominance: some believe that the Chinese deliberately released the virus from their laboratories to kill Africans, so that China can colonise Africa more easily. This belief is perhaps supported indirectly by the growth in the Chinese presence and investments in Mozambique and other African countries over recent decades. Others believe that the Chinese were using the virus to kill Americans and their other enemies, but then it got out of control and spread to the rest of the world. Others have a less radical view, believing that the spread of the virus was not deliberate, but happened because the Chinese allowed the virus to escape from their medical laboratories by mistake. Some interviewees had also heard that the virus appeared after some Chinese had eaten bats and other wild animals. However, this narrative, despite now being presented as the true cause of the virus by health organisations around the world, has not been entirely convincing to many Mozambicans. As one farmer in Tete, a man in his mid-thirties said:

There are also rumours spreading in Mozambique that China is actually going to use the vaccine that is supposedly being developed to prevent the virus to kill even more people. Some also believe that the protective masks people must wear may be causing rather than preventing the spread of the virus. Distrust in official government information gives further life to these rumours.

One consequence is that many Mozambicans are now avoiding contact with Chinese who reside in Mozambique. Fortunately, only one case of direct assault against them has been reported, but interviewees nonetheless state that they are keeping an extra distance from the Chinese on the streets and in shops.

"We don’t like to shop in the Chinese shops. I am not sure that the Chinese will infect us, but it is better just to avoid them," said one interviewee in Tete.

Despite warnings from WHO that COVID-19 was still spreading in Tanzania, Magufuli publicly declared on June 8 that his country was coronavirus-free thanks to the workings of God and to the massive prayers that had been said in churches and mosques

A different but equally pervasive narrative is that the virus is caused by decreasing faith in God, and that prevention and cures are to be found in the religious domain. This is particularly being articulated by the Christian millenarian churches, which have a strong following in Mozambique today. Prophets are spreading messages via social media telling people that the only cure for COVID-19 is prayers and God’s help. A famous prophet from Chimoio claims that he has cured people from COVID-19 with herbal tea blessed by God and that avoiding the virus is a matter of having faith in Jesus Christ. He strongly criticises the government for closing the churches and for instilling fear in people: this fear, he claims, is the work of Satan, and it reduces people’s faith in God, which is causing the virus to spread.

The prophet has a huge number of followers. Although he has been criticised for making false propaganda that will encourage people not to take precautions against the spread of the virus, many interviewees are leaning towards religion and hope in God’s protection.

Religious narratives about the virus are also circulating in the region. The strongest manifestation of this is the Tanzanian president, John Magufuli. Despite warnings from WHO that COVID-19 was still spreading in Tanzania, Magufuli publicly declared on June 8 that his country was coronavirus-free thanks to the workings of God and to the massive prayers that had been said in churches and mosques. He also urged Tanzanians not to use masks and other protective materials given by donors, stating that: ‘We need to be careful because some of these donations to fight coronavirus could be used to transmit the virus.’ Magufili has also accused the health authorities of exaggerating the significance of the virus and has mocked other African countries for implementing lockdowns.

While the Mozambican leadership has taken an entirely different approach, such narratives are having an effect on people in a situation that is already marked by great uncertainties and a deep distrust of the government that predates the coronavirus pandemic. Equally affected by this situation are those Mozambicans who still believe that the virus is just a big lie, one that has been invented by the government to reap international aid and suppress the poorer segments of the population. Meanwhile, other Mozambicans are worrying that the various counter-narratives and the failure of the government to support those most in need will increase the spread of COVID-19. The simultaneous fears of coronavirus, hunger and violence can be seen as the immediate results of the global pandemic in Mozambique, but they also tell us something much deeper about the character of the political regime in the country and its history of state violence, corruption and unequal development.

This paper has been produced in connection with a DIIS-funded research project on the experiences of COVID-19 in Mozambique, Swaziland and Myanmar, of which the author has long-term research experience. It focuses on ordinary people’s views of the nature of the virus, of government reactions to it, of the COVID-19 situation’s effects on livelihoods and the sense of (in)security, and on the role of the police. The Mozambique study draws on sixteen in-depth interviews with a mixture of male and female citizens from Tete and Chimoio (central Mozambique) and an analysis of television, print and social media sources. The interviews and document analysis were conducted by Dambinho Noé, a current resident of Tete and a long-term research assistant of the author. To comply with the social distancing rules of the state of emergency and for ethical reasons, the interviews were conducted over the telephone and based on oral informed consent. All interviewees have been fully anonymised.

DIIS Experts