Confronting China on sensitive issues

- Given the hardening of China’s authoritarian regime and the far more confrontational US–China relationship, human rights and other sensitive issues will continue to disrupt Denmark’s bilateral relationship with Beijing.

- Coordinating Denmark’s position on these issues together with like-minded countries becomes increasingly important. Not for the sake of policy impact – China is largely impervious to Western criticism – but to avoid being singled out for punishment by Beijing.

- The Government’s new foreign policy strategy should clearly specify what type of relationship Denmark can/should have with China in light of recent developments.

In the past few years, we have witnessed a resurgence of liberal human rights issues and other sensitive political questions in bilateral relations between Denmark and China.

This has triggered a series of confrontations over, among other things, a satirical cartoon in Jyllands-Posten, Chinese sanctions against the Copenhagen-based Alliance of Democracies and the installation of a ‘pillar of shame’ sculpture in front of Christiansborg (housing the Danish Parliament) in solidarity with the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong. Meanwhile, bilateral relations have taken a sharp downward turn, threatening the very existence of the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership launched by Denmark and China in 2008.

While Danish governments are mandated by Folketinget (Parliament) to raise human rights concerns with Beijing, for many years Copenhagen preferred to do so in a relatively discreet manner, on the margins of bilateral meetings or together with a coalition of states in multilateral fora such as the UNHRC. Since 2019, however, human rights and other sensitive issues have come to dominate the bilateral agenda, reflecting a broader Western development as China has come to be widely seen as ‘a systemic rival’ to liberal democracy.

A like-minded grouping of Nordic–Baltic countries

In order to navigate its increasingly fractious relationship with China, the Danish government looks not only to the EU and the US for support and coordination, but also more specifically to its Nordic–Baltic partners. Indeed, as fellow democratic small states committed to promotion of liberal human rights, the Nordic–Baltic states constitute the primary group of `like-minded countries´ from a Danish perspective. Policy coordination among the Nordic–Baltic states has even been institutionalized within the so-called NB8 framework where government officials and civil servants regularly meet to discuss issues of shared interest.

The Nordic-Baltic (NB8) framework for policy coordination thus plays a role in shaping the Danish Government’s more critical stance towards Beijing.

The NB8 framework thus plays a role in shaping the Danish Government’s more critical stance towards Beijing. For instance, on 12 May 2021 the Nordic–Baltic states issued a joint statement ‘on the situation of the Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslim minorities in Xinjiang’, delivered by the Permanent Representative of Denmark to the UN.

In the statement, the NB8 countries express their ‘grave concern’ about the ‘large network of so-called “political re-education camps” [which] severely restrict the right to freedom of religion or belief, expression, peaceful assembly and association and the freedom of movement’. Accordingly, ‘we call on the Chinese government to facilitate immediate, meaningful and unfettered access to Xinjiang for all relevant UN [personnel]’.

The Twitter megaphone

Apart from the Xinjiang question, the official positions of the Nordic–Baltic states also seem closely aligned with respect to the Hongkong pro-democracy protests, the other main issue that has moved human rights to the fore of relations with China since 2019. The NB8 countries have supported various joint EU statements on Hongkong, and all their foreign ministers have been tweeting about Hong Kong to raise international awareness of the situation.

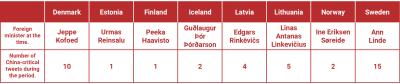

However, Twitter diplomacy can also serve to illuminate the differences that exist among the NB8 countries in terms of their willingness to use the megaphone to confront China on sensitive issues. Over an 18-month period (June 2019–December 2020), the foreign ministers of the NB8 tweeted about Chinese human rights violations 40 times in total. As Table 1 demonstrates, the Swedish foreign minister Ann Linde was by far the most frequent user of her ‘Twitter megaphone’, followed by the Danish foreign minister Jeppe Kofod, whereas their Finnish and Estonian counterparts only once referred to Chinese human rights issues in their Twitter accounts during the examined period.

Vilnius pushing the new frontier

Twitter diplomacy aside, Lithuania has recently taken a far more strident stance than its Nordic–Baltic fellows to become Europe’s harshest China critic, following elections that brought a new conservative government under Ingrida Simonyte to office late last year. In May 2021 Vilnius snubbed Beijing by announcing its withdrawal from China’s ‘divisive’ 17+1 mechanism for collaboration with East and Central Europe, while the Lithuanian parliament adopted a highly China-critical resolution referring, among other things, to the ‘genocide in Xinjiang’.

A few months later, the Lithuanian government not only upgraded its political relationship with Taiwan but allowed Taiwan to open a ‘Taiwanese’ (rather than Taipei) representative office in Vilnius, an unprecedented diplomatic gesture given Beijing’s aversion to any direct references to Taiwan as a political entity.

Most recently, the Lithuanian government made international headlines by urging its citizens to get rid of their Chinese-made phones, because of in-built censorship tools that can allegedly be remotely activated to detect sensitive terms like ‘free Tibet’.

Indeed, all the Nordic–Baltic countries, and particularly Lithuania, have already seen their bilateral relationship with China deteriorate in a fundamental way over the past few years.

In response, Beijing has, for the first time since the 1990s, recalled its ambassador from a European country and exerted different kinds of informal economic pressure on Lithuania, including by disrupting the supply of Chinese-made items to Lithuanian manufacturers. In this case, China’s economic coercion has been blunted by the quite limited scale of bilateral trade and investments between the two countries. However, since other Nordic–Baltic countries have more at stake, they seem less likely to follow this new, ‘red line-crossing’ trail blazed by Vilnius, even though their foreign ministers expressed solidarity with Lithuania during an NB8 meeting in mid-September.

Zooming out: underlying drivers

Although the other Nordic–Baltic states are unlikely to go as far as Lithuania, human rights concerns and other sensitive political issues will continue to disrupt their relations with China for two main reasons.

First, China’s development under President Xi Jinping has significantly increased the political differences between China and the West. Not only because of various steps to centralize and consolidate power around Xi as core leader, but also because of the hardening of the Chinese regime with respect to its handling of human rights issues. Especially Beijing’s repression of the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests and its systematic violations of human rights in Xinjiang have been an ‘eye-opener’ according to many, centrally placed, sources in the Nordic–Baltic countries.

Second, since 2018 the United States has adopted a far more competitive approach to China, directly confronting Beijing on various issues, including human rights. While the Trump administration’s quite erratic and instrumental approach did much to draw international attention to Chinese human rights violations in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, the Biden administration has framed human rights issues as part of a more comprehensive ideological contest between democracies and autocracies.

As this agenda involves closer policy coordination on human rights issues with its Western partners and allies, the Nordic–Baltic states can expect the US government to continually call on like-minded states to join it in criticising Chinese human rights violations. Because of these underlying development trends, the recent resurgence of human rights and other sensitive issues will – alongside growing security-related concerns about the rise of China – continue to put a strain on relations with Beijing. Indeed, all the Nordic–Baltic countries, and particularly Lithuania, have already seen their bilateral relationship with China deteriorate in a fundamental way over the past few years.

The difficult path ahead for Copenhagen

Back in 1989, following the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Danish Government took a very proactive and critical stance; it was the first to submit an official protest to the Chinese Government and also spearheaded the adoption of sanctions against China. Fear of reprisals played little role back then, but in the meantime, Beijing has demonstrated on numerous occasions that it has both the capacity and the willingness to punish its critics with sanctions, as Denmark has learnt the hard way twice: in 1997 for sponsoring a resolution critical of China in the UNCHR and again in 2009 for hosting an informal meeting with the Dalai Lama.

As the current Danish Government, in its relations with Beijing, seeks to strike the right balance between human rights issues, growing security concerns, economic interests and the need to engage China on a range of global issues, the importance of policy coordination with like-minded countries will only grow. As such, Denmark’s bilateral relationship with China seems less important today, despite ongoing efforts to renew the joint work programme for the strategic partnership announced in late November during Danish foreign minister Jeppe Kofod’s surprise visit to China.

Tellingly, however, media coverage of his visit focused on sensitive political issues, this time on whether Denmark had changed its approach to Taiwan (the ‘one China policy/principle’) as Chinese state media covering the meeting seemed to suggest.

DIIS Experts