Asia beyond China

Much of Europe’s attention to Asia is currently being captured by China. However, if the European Union and its member states are serious about maintaining a rules-based global order and advancing multilateralism and connectivity, it should increase its work in building partnerships across Asia, particularly in the Indo-Pacific super-region. To save multilateralism, go to the Indo-Pacific.

■ Targeted connectivity. The EU should continue to offer support to existing regional infrastructure and connectivity initiatives.

■ Work in small groups. EU unanimity on China and Indo-Pacific policy is ideal, but not always necessary to get things done.

■ Asia specialists wanted. Invest in and develop career paths for Asia specialists in foreign and defence ministries and intelligence services.

From the Arctic to the South China Sea, in Europe the debate on China’s rise is often framed around the big power rivalry between the United States and China. The economic and security consequences of this new strategic competition are significant, but Europe’ s fixation with it can distract from new thinking and actions the EU and its member states can take in global affairs.

Nowhere is the EU’s strategic lethargy more evident than in the Indo-Pacific. This super-region, spanning the Indian and Pacific Oceans, is home to some of the world’s largest and fastest growing economies and some of its most troubling security hotspots. France has an Indo-Pacific strategy and conducts freedom of navigation patrols in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait. But even though the EU is a major trader and investor in the Indo-Pacific, much of this engagement lacks strategic direction. The COVID-19 pandemic has only reinforced the necessity for the EU to rethink Asia, as there is much European countries can learn from a host of Asian countries, such as South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, on how to control the spread of the coronavirus most effectively.To deal with China’s rise, Europe must deal with the rest of Asia.

An Asian idea

‘It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia, and uphold the security of Asia.’ This statement by China’s president, Xi Jinping, at a 2014 summit speech in Shanghai was largely seen as a response to America’s ‘pivot to Asia’. From Beijing’s vantage point, American backing for the Trans-Pacific Partnership at that time, before President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal, was designed to contain China’s rise. Beijing’s concerns returned in 2017, after Trump announced his administration’s vision of a ‘ free and open Indo-Pacific’. This looks to promote sovereignty, freedom of navigation and reciprocal trade, but still clashes with Washington’s agitation of many of its trade and security partnerships.

As Australian professor Rory Medcalf argues, the Indo-Pacific is both a place and an idea, reflective of changes in commerce, strategic behaviour and diplomatic partnerships across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and of the growing role of India, Indonesia and other regional powers. China is dismissive of the Indo-Pacific, viewing it as an idea of American design and direction that threatens to upset a China-centric regional order as enshrined in its Belt and Road Initiative. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, comparedthe Indo-Pacific and the so-called Quad, a security dialogue between the United States, Japan, Australia and India, to sea foam in the Pacific or Indian Ocean: ‘they may get some attention, but soon will dissipate’. China’s state media mouthpiece, the China Daily, has called the Indo-Pacific idea ‘divisive in nature’ and an ‘‘America First’ ploy’.

This wide acceptance of the Indo-Pacific idea across Asia should encourage the EU to become more deeply involved in the region’s economic development and maritime security cooperation.

Yet the Indo-Pacific idea and its development into a strategy are not of American origin. As Xi suggested, Asians are indeed looking to maintain regional security themselves, and that entails deterring China’s assertiveness and military expansion. In 2007, the Indian strategist Gurpreet S. Khurana gave new life to this dated geographical concept in order to highlightthe threat China posed to sea lines of communication across Asia’s oceans. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe then evoked the Indo-Pacific in a major speech to the Indian parliament that year. As China expanded militarily into the South China Sea over the following decade, others in the region, including Australia and Vietnam, further embraced the Indo-Pacific as a policy platform for developing new economic and security cooperation. Indonesia’s President Jokowi Widodo is also advancing an approach under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

There are different interests attached to the Indo-Pacific strategies that are currently under development, but each advances a broad recognition and support for the rule of law, freedom of navigation and free trade. China is not excluded from this vision, but its overt militarization in the South China Sea and aggression in the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait contrast sharply with how its neighbours are seeking to manage Asian affairs.

This wide acceptance of the Indo-Pacific idea across Asia should encourage the EU to become more deeply involved in the region’s economic development and maritime security cooperation. This is not to pick sidesin the US-China strategic competition, but to back a rules-based order and multilateralism that most European and Asian countries endorse.

Weaponizing connectivity

Economics has never operated in a world isolated from politics and security, but in recent years trade has been leveraged more readily as a means of coercion and strategic influence. As professors Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman argue, it is mainly the United States that holds the power to weaponize interdependence. Yet China is also exploiting its jurisdiction over economic networks of commerce, resources and information. Its economic outreach to the rest of the world offers opportunities for growth and development, but from trade to tourism, Beijing is not shying away either from weaponizing connectivity for strategic gain.

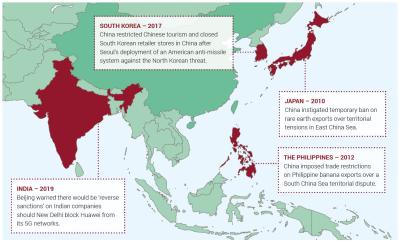

China’s economic coercion mainly aims to shape the foreign and defence policy decisions of foreign governments by restricting trade and investment access to its large market or barring Chinese tourists from travelling to targeted countries. This is not simply a product of US-China strategic competition but has been long deployed by Beijing across the Indo-Pacific. The list of European countries facing similarpressure from Beijing, mainly on political grounds involving Tibet and Taiwan, only grows with each passing year.

China’s economic coercion in the Indo-Pacific: selected cases

While the effectiveness of China’s trade weapon is debatable, Beijing continues to test and expand its use. It is now reacting not only to self-determined violations of its core interests around political and territorial issues, but expanding this list to include strategic interests that involve critical infrastructure and technology. In Asia, Australia, New Zealand and India have all encountered pressure from China if the moved forward with barring the Chinese telecom Huawei from participating in their 5G networks. European countries, including Germany, the United Kingdom and the Faroe Islands, have also been caught in a tug-of-war between China and the United States, both trying to dictate the technology decisions of other sovereign states. For both European and Asian governments, this pressure further blurs the line between trade and security policy, which cannot easily be isolated from one another.

Multilateralism first

So far, American President Donald Trump has spent his years in office alienating close trade and security partners. Yet China too has become increasinglyassertive in advancing its geopolitical and geostrategic aims in blatant disregard for international rules and norms. Europeans need to respond to the fact that both the United States and China are undermining the global order and to unpack the degree to which each is upsetting European positions.

Working alongside the United States and China is still very much necessary, as in efforts to support freedom of navigation in the South China Sea or to reform the World Trade Organization, but these interactions should not be used to promote hierarchical and transactional visions of the global order. If the EU works towards fostering partnerships in the Indo-Pacific that empower multilateralism and free trade, common rules and regulations on trade and infrastructure development will push back against the arbitrary and assertive exploitation of connectivity as a tool of economic coercion.

Engaging Asia beyond China can drive forward both trade and connectivity and the maintenance of the rules-based order. Last year’s EU-Japan free-trade deal represents a step in the right direction, but increased policy attention should be given to trade deals with India and ASEAN partners, including managing domestic hurdles to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Foreign investment into ASEAN is already higher than that heading into China. The EU is the largest investor in the region, but the Netherlands makes much of this total, demonstrating that there is further room for diversification.

For foreign and security policy, while it is ideal, it is not necessary to have the entire EU membership behind new initiatives. Small leading groups can move ahead on their own, showing the benefits of closer ties with Asia and encouraging others to join in. A recent poll of ASEAN respondents found that they are eager for their countries to take part in regional security initiatives such as the Quad, and look to Japan and the EU to fill any American absence.As the world wrestles with fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital for the EU to work more closely with Asian countries on best practices to stem its spread and other outbreaks in the future.

Supporting international rules-based connectivity is central to European interests in the Indo Pacific. As detailed by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, the Belt and Road Initiative enhances the logistical possibilities for traders, but its development is largely closed to foreign participation. The EU’s connectivity plan aims to promote open and transparent infrastructure development. To ensure implementation is not spread too thin, the EU should focus its efforts within Europe’s borders and its near-neighbourhood, but it can stay active in the Indo-Pacific by empowering other initiatives that advance international rules-based connectivity. This includes working with Japan’s Partnership for Quality Infrastructure and activities in Southeast Asia, Australia’s engagement in the South Pacific and the American-launched Blue Dot Network. Washington may limit the extent to which climate issues are prioritized, but the EU can advance these goals with others, including China, while still pushing for transparency and financial sustainability in infrastructure development alongside the United States. What is essential is that the EU stays anchored in supporting initiatives that advance inclusiveness and international rules-based connectivity across a broad set of like-minded Indo-Pacific countries.

European countries from Germany to Denmark have been criticized for having little in the way of a foreign policy agenda beyond advancing trade and commercial interests. But in a changing global order, the overlaps between trade, technology and security require EU member states to learn to measure policy success beyond euros and cents. For such transformations to take place, European foreign ministries cannot remain under-funded and under-staffed. In a multipolar world, robust diplomacy is essential to navigate and push back against big power pressure. Asia expertise is crucial to build new relationships. From emerging economies and large democracies like India and Indonesia to advanced ones such as Japan and South Korea, there remain plenty of untapped opportunities for Europe in the Indo-Pacific.

DIIS Experts