Armed groups are here to stay

■ Push for pragmatic political engagement with ANSAs. Lack of engagement by states and donors decreases civilian protection.

■ Consider funding professional networks, further research and training in modalities for effective engagement with ANSAs.

Armed non-state actors are significant players in most conflicts. The international community is often forced to engage with them in order to secure humanitarian aid for civilians or to end armed political conflicts. The question of when and how to engage is being debated. We suggest a more pragmatic approach.

Most conflicts today involve armed non-state actors (ANSAs) who fight against state forces and/or other ANSAs. These actors, ranging from insurgent armies and militias to vigilantes and urban gangs, exercise some degree of control over territory and populations. Some enjoy a degree of legitimacy among populations because they have stepped into power vacuums and provide justice, security and other public services in the areas under their control. Some even have relief departments and health committees. The international community is slowly recognising this and taking it into account as a factor when engaging in conflicts.Based on interviews with key humanitarian actors and specialised agencies in Geneva and New York, we observe a shift in engagement with ANSAs, from a sole focus on humanitarian access and delivery of assistance towards an engagement for political ends and conflict resolution. The ultimate aim of engagement is now, increasingly, to end violence.

Engagement with ANSAs is not only about humanitarian access, but increasingly about protecting civilians and creating a political space for the resolution of armed conflicts.

Engagement for humanitarian purposes

Since the early 2000s the international community’s engagement with ANSAs has been limited – not least by rules intended to cut off funding for proscribed terrorist organisations – and has focused on humanitarian access rather than protection of civilians or conflict resolution. Delivery of humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected populations has been central to the concerns raised by many stakeholders such as the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the International Committee of the Red Cross and the World Food Programme.

In order to get humanitarian access international agencies and NGOs engage with the armed wings of ANSAs, but when it comes to services such as healthcare they engage ANSAs’ relief departments. Whether services such as education and wider healthcare provision should be an issue of engagement has raised some debate among humanitarian actors, as they are not seen as part of the immediate efforts to save lives. ANSAs acquire legal obligations under international humanitarian law when they take control of territory and populations. According to practitioners working with ANSAs there is clearly a fear among state actors of legitimising armed groups by recognising these obligations. Moreover, ANSAs are also uncertain about their responsibilities, and are reported to ask: ‘are we obliged to follow international humanitarian law? Is it our responsibility or not?’

■ Provide services such as education, employment, protection, justice, security etc.

■ Have a hierarchical organisation and clear command structures.

■ Control territory.

- Skyrocketing humanitarian needs coinciding with a historic shortfall in the funding required to meet them. Widespread state fragility marked by extreme poverty and weak/absent institutions are among the factors that are contributing to this unprecedented spike in humanitarian needs.

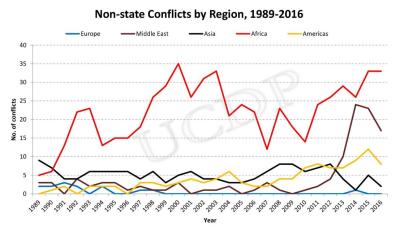

- The explosion of ANSAs since the Arab Spring in 2011 and the onset of the Syrian civil war (see graph). At the same time, key stakeholders recognise that in situations of conflict and state failure some ANSAs may be ‘governments in waiting’, acting as de facto authorities. In some cases they are the only existing partners for dialogue with the international community.

- The ANSA’s popular support.

- Its provision of services.

- Its control over territory.

- The political grievances.

- Whether the ANSA’s involvement is crucial to the resolution of the conflict.

- Its command structure.

- Whether it seeks to comply with international humanitarian law.

Pragmatism vs. the fear of legitimising ANSAs

The aide memoire has not received the promotion and public attention it deserves. UN bureaucrats are ready to point out that the process of writing the aide memoire was a difficult balancing act. Member states, and in particular those engaged in conflict with ANSAs, do not favour, or are not comfortable with engaging ANSAs. Their biggest fear is that engagements legitimise and recognise these actors and hollow out the state’s sovereignty. While some states allow humanitarian engagement with ANSAs and others turn a blind eye to it, many states reject engagement and accuse ANSAs of using international and non-governmental organisations for the purpose of gaining legitimacy and recognition. Bureaucrats in the UN, however, consider it necessary to engage with ANSAs and hold that engagement never legitimises ANSAs. In the words of one interviewee: ‘We need to speak to whomever we need to speak with for our operations. No need for states to give us permission to do what we do’. And yet, the potential for gaining legitimacy is the strongest incentive when it comes to convincing ANSAs to participate in any humanitarian or political dialogue.

Pragmatic engagement with ANSAs runs counter to years of non-engagement due to counter-terror policies and terror listings in particular.

Principles of engagement could guide international and state practices, as suggested in a recent brief from Chatham House. Yet experience suggests that these are often only followed when it suits states’ own political agendas and geopolitical ambitions. In the world of sovereign states behaviour differs and sometimes states can be reluctant – if not dismissive – when it comes to humanitarian and political engagement with ANSAs. International engagement, however, is dictated by the immediate practical conditions and potential effects of ‘talking’ to ANSAs, rather than any normative or principled framework. Thence this call for pragmatism. In other words, a call for ‘doing what works best’ in any context, and for the acknowledgement of real world conditions that constrain actions and impact the results of those actions. The emergent trend towards a pragmatic engagement with ANSAs runs counter to years of non-engagement due to counter-terror policies and terror listings in particular. Hopefully this can lead to a more realistic strategy towards, and a systematic engagement with, ANSAs with the purpose of ending armed conflicts. Nevertheless, there remains a need for developing more knowledge and a better understanding of ANSAs, the populations living under their control, and the dilemmas of engagement and legitimisation, as well as for training and sharing of experience among practitioners in the field of political engagement with ANSAs.

DIIS Experts