Can a military coup correct a failed democracy?

As Mali’s new military junta takes over the capital Bamako on August 18th, I follow the events on my computer screen here in Denmark. A few hours after the coup leaders detain President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita and a number of other government officials, the president appears on the screen of the national TV station ORTM, exhausted and wearing a facemask, and declares his resignation. At the same time, he dissolves the government and the national assembly.

At first glance, the current coup is similar to the coup in 2012. Both originated from the same military barracks in the dormitory town of Kati, 15 kilometres from the capital. At the time, it came as a surprise to the many international donors that the country, which for many years was considered a pioneer for democracy, collapsed like a house of cards in just a few months. A surprise that most of all reflected how Mali’s many Western donors either did not see or closed their eyes to the widespread corruption among the political elite.

The coup in 2012 triggered a massive security collapse in the country and became a central focal point for France’s, the EU’s, the UN’s and countries like Denmark’s military presence in the region. The link between our own security and the threats that unfolded in the Sahel region was quickly established in the speeches and strategy papers of various European politicians. If we do not fight terrorism, migration and borderless crime in the Sahel region, it will hit Europe, it was said. Having learnt from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the West did not want a long-term presence. Instead, the capacity to take care of the region’s security, and thus Europe’s, would be built locally.

More troops, more attacks

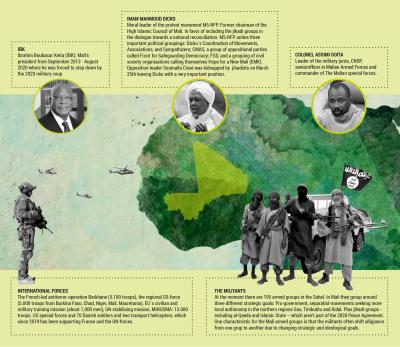

But it did not go as smoothly as that. In January 2013, France’s military entered its former colony with the Danish-backed Operation Serval, with the aim of containing the jihadists’ progress as quickly as possible. Since then, more soldiers have followed. Today, there are 5,100 French troops, 5,000 regional troops, 1,000 EU troops, 13,000 UN troops and several hundred US troops in Mali, as well as the 70 Danish troops and two transport helicopters that have supported French and UN forces since November 2019.

Despite the many troops and new efforts in the country, the number of attacks in the region has increased fivefold since 2016. Most take place in the isolated border areas between Burkina Faso, Niger and in Mali itself. Here, the state is absent and the jihadists have had success in recruiting amongst the most vulnerable sections of the population.

Since the coup, I have been communicating via WhatsApp with my contacts in Mali to get the local perspectives on the events behind the news flow and the quick SoMe analyses. My conversations over WhatsApp are a continuation of my fieldwork in Mali over the past two years. Here, popular protests have long shaped the mood in the capital and left me with the impression that it was only a matter of time before a radical change of government would occur.

In a telephone conversation with my research assistant Philibert Sylla, who is a PhD student at the university in Bamako, I sense a cautious hope of a better future growing. A hope that is Mali’s own. Malians like Sylla have a different perspective on events from Western news channels, which have quickly added the coup as yet another chapter in the ongoing history of failed African states.

Despite the similarities, the 2020 coup has its own logic. Already a few days after the remarkably non-bloody events, the state administration is functioning relatively normally. Public employees are at work and the banks are open again. However, money transfers from neighboring countries have been blocked as part of the West African co-operation organization ECOWAS’ new sanctions against Mali. Together with the rest of the international community, ECOWAS has condemned the coup and sought to negotiate an agreement with the military junta on the transition to civilian-led rule. Though still without result.

At that time, the motto amongst the soldiers was ‘if you die for Mali’s sake, you die for nothing’

Nevertheless, many people in Mali right now think back to the 1991 coup as a historic moment of democracy. A moment that is perhaps more reminiscent of what we are seeing now than of the coup in 2012. In 1991, the coup preceded the extensive peace process that ended the 1990s Tuareg uprising and the ensuing bloody civil war. The coup in 1991 was led by Amadou Toumani Touré (ATT), who after one year handed over power to the civilian authorities, after which elections were held. By virtue of his reputation as a ‘soldier of democracy’, ATT was elected president 10 years later. A post he held until he was ousted in the 2012 coup.

From coup d’etat to coup corrective

The military coup in 2012 came in the wake of the international bombings in Libya that led to Colonel Gaddafi’s fall. Thousands of heavily armed Tuareg rebels, who had been in exile in Libya, moved into the northern regions of Mali with a desire to establish an independent state, Azawad. Here, they initially fought side by side with Al-Qaeda-related jihadists against Mali’s army, which at the time consisted mostly of soldiers in sandals who either fled or were mowed down at their sparsely armed bases in the north. At that time, the motto amongst the soldiers was ‘if you die for Mali’s sake, you die for nothing’.

Dissatisfied with being used as cannon fodder in the fight against jihadists and Tuaregs, a group of younger lower-ranked officers led by Captain Sanogo took the matter into their own hands. They overthrew the then government in tumultuous circumstances, where several lost their lives while the then president ATT fled. ECOWAS quickly condemned the coup, deposed those behind it and got a transitional government on its feet within a couple of months. But not least because of the power vacuum in Bamako, jihadist rebel groups had the opportunity to consolidate themselves in the northern regions.

A scenario the international forces here in 2020 fear will once again will bolster the jihadists, whose attacks have moved closer to the capital than ever before.

Already then, there was great dissatisfaction with the president’s government and the growing corruption. But in 2012, it was mostly mothers and spouses of the Malian soldiers who protested in the streets of Bamako. They wanted better salaries for the soldiers, who were abandoned by their commanders-in-chief. The uprising was most pronounced within the military’s own ranks, who concentrated their energy in the capital, where the coup took place a few weeks before the announced elections.

The coup was quickly declared a disaster. In 2012 , the coup leaders and the political coalition that subsequently supported it profited from strong anti-colonial sentiments in the population (especially directed at the former colonial power France). For that reason, they were also against the presence of international troops in the country and did not recognize the UN’s and ECOWAS’ plan for the transition to democracy.

For many in Mali, this is not an actual coup – rather a coup corrective. A necessary evil to get democratically rooted reforms

But last week’s reports from Mali show a different development. One of the key differences from the coup in 2012 and now is that the 2020 coup comes in the wake of the massive popular protests that have filled the streets of Bamako since last year. The crowds, who pay tribute to the new military leaders with banners and shouts and the characteristic hoarse sound of the many vuvuzela plastic horns, are part of a broadly rooted protest movement. After the coup, people were first out on the streets of Bamako. Then the central cities of Kayes, Segou, Mopti and Timbuktu joined the choir.

For many in Mali, this is not an actual coup – rather a coup corrective. A necessary evil to get democratically rooted reforms. In its own way, the ‘coup’ provides possibilities for finding new solutions to the existential crisis that, despite massive international presence, no one after eight years of war has been able to resolve. The now resigned president IBK has not fulfilled his 2013 election promises of poverty reduction, peace, security and national reconciliation. He has most of all aggravated the situation.

The protest movement and the imam who unites

Firstly, people have protested against IBK’s and the international forces’ lack of action against the escalating violence in the country. Two-thirds of the country is in a state of emergency, jihadists are stronger than ever, and according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 275,000 Malians are refugees or internally displaced. Between 2012 and 2019 in Mali and neighbouring Niger and Burkina Faso, there have been 1,463 violent clashes, with 4,723 civilians killed at the hands of the 195 different armed groups. The violence reached its highest level in 2019 and continues with increasing frequency. here are weekly reports of soldiers who die from either explosions or attacks by jihadist groups. Some estimate that close to 4,000 Malian soldiers have lost their lives since 2015. But it is not easy to get an accurate picture of the numbers, and the army has often been accused of underreporting the death toll. But almost everyone in Mali knows someone who has been killed.

Mali’s population has suffered enough under IBK’s regime. Uncertainty and corruption have grown. And what has the international community done to make it possible for our children to go to school, to avoid the massacres in Ogossagou and Sobane Da? You have seen for yourself how the internally displaced suffer under the conditions such as in the Faladié camp. But when the security forces fired directly at the protesters, it was the last straw

In addition to the serious security situation and rising food prices, schools have been closed for almost two years. Teachers, prison guards, health workers and other civil servants have not been paid, and unionized civil servants are still on strike.

The poor conditions are in stark contrast to countless corruption scandals, the president’s purchasing of private jets and unused military helicopters have filled the newspapers and social media. Not least images of the president’s son, who is chairman of the parliament and the security committee, celebrating a birthday party in luxurious surroundings in the Mediterranean sparked protests.

The protests escalated in earnest in the wake of the spring parliamentary elections, in which the constitutional court wrongfully allocated 31 seats in parliament to the government party. A broad coalition of civil society actors, trade union movements and opposition politicians then formed the protest movement (M5-RFP, the June 5 Movement, which brings together patriotic forces) demanding IBK’s resignation.

The movement was spearheaded by Imam Mahmoud Dicko, a controversial national conservative, non-violent political figure who, as former chairman of Mali’s highest assembly of Muslim leaders, has gained a central position in Mali’s political arena. Since 2017, the imam has gone from supporting IBK to openly fighting the government.

He has previously headed the government’s dialogue with the jihadists, but since 2018 he has been side-lined by the president. But according to several of my Malian sources, the population’s desire for reforms cannot be reduced to a showdown between the government and Dicko.

As a rallying figure for M5-RFP, Dicko has gained status as a kind of guarantor of popular morality. He has won great popularity by addressing ordinary people’s central complaints: the government’s (and the international forces’) inability to create peace in the country, the pervasive corruption, electoral fraud and people’s terrible living conditions. At the same time, he can also urge restraint and call for peaceful solutions. To him, it is clear that France’s and the UN’s presence, who in no way wanted to ‘rock the boat’, has contributed to the president’s immunity.

During the protests in July, another red line was crossed when the government’s anti-terror corps fired directly into the crowd, killing at least eleven and wounding over a hundred. The wrongful use of the anti-terrorist corps (formed after the terrorist attack on the Radisson Hotel in Bamako in 2015 with support and subsequent training from the EU, France and the US) sealed the people’s distrust of the government.

‘After the people’s blood flowed in the streets, the country could not continue with IBK at the helm,’ Philibert Sylla said at the time over the phone.

In the days after, ECOWAS still tried to find a solution with IBK at the helm. But it was not welcomed by the protest movement. Therefore, many see the coup as a way of sparking necessary change.

Mali’s new military junta was trained by the West

The coup plotters, who call themselves the National Committee for the Salvation of the People, consist of a number of senior officers from the middle tier of the military hierarchy. In their launch on the national TV station ORTM, the junta leaders present their intentions.

- They want to hand over power to a civilian-led government.

- They accept the peace agreement with the groups in the north from 2015.

- They want to continue the cooperation with France and the international troops in the country.

Since then, they have released IBK and launched a four-page legal document setting the framework for their temporary takeover. Respect for democracy, human rights and international conventions is paramount.

At the base in Kati, the sandals and the slightly casual-looking uniforms made by local tailors have been replaced by military boots and real uniforms. But corruption has only worsened in line with the many foreign resources that have been thrown into the dysfunctional system

On a poor connection to Bamako, Philibert, who regularly talks to military people, explains: ‘Although there is still massive dissatisfaction with the widespread corruption within the army, the takeover seems better planned than in 2012. The military junta is made up of intelligent people, and they are ready to cooperate with the UN, France and the international forces. If you notice, unlike in 2012, the military has not left their posts in the central and northern parts of the country. But the really big difference is that they know that this time they cannot get away with anything. The opposition will not accept the military junta taking hold of power. And that’s not what they say they want either. There will be a massive popular upheaval if they do not meet the opposition movement’s demands for improvements.’

Since 2012, Mali’s international security partners have improved the soldiers’ standard and professionalism. At the base in Kati, the sandals and the slightly casual-looking uniforms made by local tailors have been replaced by military boots and real uniforms. But corruption has only worsened in line with the many foreign resources that have been thrown into the dysfunctional system. In 2015, among other things, a law came into force that was meant to demonstrate IBK’s intention to change the soldiers’ conditions in the light of the many security challenges. The law approved massive investment in the army of 1,230 billion West African CFA francs (almost 14 billion Danish kroner) in the period 2015–2019. In principle, the soldiers’ salaries should almost double, and a risk premium was introduced as well as extra supplements for those sent to the northern and central parts of the country. But as the soldiers on the front tell it, the corruption is worse now than in 2012. Back then there was also corruption, but the cake was shared. Now the soldiers never receive their pay rise. It simply disappears.

The boomerang effect of international military interventions

International media reports gradually reveal that several of the new junta’s people have been trained by the Americans, who have been present in the region since 11 September 2001. But France and other European countries have also been involved in the training as part of their capacity-building programmes of the army. Colonel Assimi Goita, who has declared himself temporary leader of the military junta, has for years participated in US-led counter-terrorism training in the Sahel region. Goita himself has fought on the front line in the northern and central regions, which have been hardest hit by the escalating spiral of violence and attacks by Islamic State and Al-Qaeda. The United States has now suspended all support for Mali’s army, and shortly afterwards the EU followed suit and has also suspended its training programmes. Undaunted, France continues their fight against terrorism.

Meanwhile, this moment should provide time for reflection for Mali’s many international partners. The extensive training of Mali’s security forces testifies to the many international interests in the country. But if Europe’s leaders believe that our own security depends on Mali’s, we should also listen to what the people of Mali want

Meanwhile, this moment should provide time for reflection for Mali’s many international partners. The extensive training of Mali’s security forces testifies to the many international interests in the country. But if Europe’s leaders believe that our own security depends on Mali’s, we should also listen to what the people of Mali want.

The coup is an unpleasant reminder of the unpredictable effects of the international military engagements. The international forces have trained the soldiers in everything from simple shooting techniques to tactical operations. Radios, protective equipment and tanks have been purchased. The EU has, for instance, persistently attempted to help improve the army’s HR management system. But especially the lack of necessary reforms in the security sector causes the problems in a dysfunctional state to replicate themselves. Therefore, the coup is an example of a boomerang effect, where international intervention efforts end up creating further destabilization in Mali. Both because the unintended consequences of the efforts are not recognized, such as when the specially trained soldiers suddenly seize power, but also because such efforts indirectly provides support to a regime in déroute.

In Mali, the army also has civilian blood on its hands. A number of reports show that Mali’s armed forces have imprisoned civilians without trial and in several cases have committed abuse and carried out executions. In addition, senior officers in the army are accused of supporting self-defence militias in central Mali (not jihadists), who have committed massacres on civilians in recent years. Nevertheless, the international forces’ legitimacy and legal basis for being in Mali depends on an invitation by a formally recognized government. However, this limits the demands they can make.

Even though security sector reforms have been at the top of both the UN’s and the EU’s priority list, it is an agenda they have not been able to push through. Instead, the presence of international forces has boosted the government’s power by adding resources to the security sector without there being consequences for the massive money laundering. Not always because of bad intentions, but because military operations in an extremely complicated political context often become the art of the possible. As several EU security experts in Bamako have explained to me, Mali’s Ministry of Internal Security and Civil Protection has consistently refused to disclose how many employees there are in the army. They have never wanted to publish an actual budget of their running costs. No one knows where the money is going.

The international actors may have been too preoccupied with keeping the elected government in power while ignoring the people’s wishes. But, as the Malians say, the government is for the people. Though the international community insists on having a constitutionally legitimate government at the helm, the IBK government has not respected the constitutional order and the rules of good governance.

New water in old bottles?

Right now, everyone’s eyes are on the junta and their next step towards establishing a government that the international community can accept. Although Philibert Sylla and several other Malians I have spoken to see a budding hope, others argue that the new coup is merely history repeating itself. The coup plotters overthrow the government due to dissatisfaction, but when they themselves come to power they continue the same corrupt style of leadership. Only time will tell if the junta manages to meet the people’s expectations. A civilian-led transitional government would clearly be preferable, not least in light of the army’s controversial role in the conflict.

History has shown us that haste is a burden for peace in Mali. In the first instance, a broad reconciliation process is needed. And here, Imam Dicko and the religious leaders play a central role. France has feared that Dicko would impose a religious regime in Mali. But according to Dicko himself, he is and will remain an imam. Equality or LGBT rights are not likely to be at the top of his priority list, but as a religious leader he may be able to bring together the warring parties in the country. He has invited representatives of the warring Fulani and Dogon peoples to dialogue – and to agree that they will help restore peace in Mali. It is going to be difficult, but Mali has done it before. The extensive national reconciliation and dialogue processes following the civil war in the wake of the 1990s Tuareg uprising are one of the reasons why Mali became known as the pioneer of democracy in Africa. The state did not fail because the old peace agreements were fruitless. But because they were never implemented.

Mali’s challenges have multiplied since the Tuareg uprising of the 1990s. But as Philibert concludes over the phone: hope has been awoken. The youth are on the streets. And they will no longer accept the military junta or religious leaders betraying the trust they have shown them by placing the country’s future in their hands.